Sex, Drugs, and Ay Ziggy Zoomba

UNC and Bowling Green are polar opposites, yet they both share a weird fight song. Why? Blame a man who the CIA drugged with LSD, wrote lots of erotic novels, and sang a song that makes no sense.

Over the summer, I was listening to a podcast from Joe Ovies and Joe Giglio about the 25 greatest Triangle sports soundbites of the last 25 years. There were some real bangers in there (“The ceiling is the roof,” “bunch of jerks,” and so on), but the one that caught me by surprise was this one, from then-UNC football coach John Bunting:

In this clip from roughly 20 years ago, Bunting leads a crowd in a strange chant:

Aye zigga zoomba zoomba zoomba

Aye zigga zoomba zoomba zay

Aye zigga zoomba zoomba zoomba

Aye zigga zoomba zoomba zay

Roll ’em down you Tar Heel Warriors

Roll ’em down and fight for Car-o-li-na

It’s not like this song’s a big secret. Aye! Zigga Zoomba is listed as one of the official UNC songs. There’s a glee club version. A marching band version. It’s not played as often as the fight song or the alma mater, but it’s a sanctioned part of Tar Heel lore.

I knew this song well. But until now, I had no idea it had anything to do with UNC.

I grew up in Ohio, and some friends of mine went to Bowling Green State University. To a person, if I asked them “What’s ay ziggy zoomba?” they would immediately sing the entire song, on the spot. Any BGSU grad will do this! Try it if you can find one! The only differences are the university-specific lines:

Roll along you BG warriors

Roll along and win for B-G-S-U!

Today, “Aye! Zigga Zoomba” is a niche part of Tar Heeldom. But “Ay Ziggy Zoomba” (and its slightly different spelling) is basically Bowling Green’s whole identity1. This spring, the football team welcomed new head coach Eddie George with a jumping ay ziggy zoomba chant. It’s in the EA Sports college football game. It’s a hashtag. Students say it to each other. There’s a college bar named Ziggy Zoomba’s The university has stated that “Ay Ziggy Zoomba” are magic words. There’s even a scene in the 1968 Alan Alda movie “Paper Lion” in which a Detroit Lions rookie from Bowling Green gets up on a chair to sing the song.

Now look. Back in the day, it wasn’t exactly unusual for colleges and universities to borrow what we might today refer to as intellectual property. I’ve written in the past about how one man at one company designed a ton of cartoony college sports logos, hence UNC’s Rameses logo was once identical to the logos of at least four other universities. A bunch of colleges and universities have alma maters that sound the same, albeit with different words. High schools basically steal fight songs from higher ed. I was in the Lakeview High School marching band in Ohio, and our fight song was the Ohio State Buckeyes’ “Across the Field.” We weren’t alone.

But as far as I can tell, only two universities use “Ay Ziggy Zoomba”: North Carolina and Bowling Green2. What else do they have in common? Not much. The schools are about 500 miles away from each other, but might as well be worlds apart. UNC is America’s first public university. Its students get dressed up for football games. The campus is extremely Southern. The skies and school colors are Carolina Blue. Bowling Green, by contrast, sits in the middle of flat-ass northwest Ohio farms. The school colors are orange and brown (the Cleveland Browns stole their colors, not the other way around). BGSU wasn’t founded until 1910. The student wardrobe seems to be the hoodie. It’s cold and windy as hell in the winter. I once accompanied a friend of mine outside in January for a smoke break, and it was one of the worst weather experiences I’ve ever had in my life.3

The schools don’t really ever play each other either, at least not in the sports where you’d have a band playing “Ay Ziggy Zoomba.” The football teams squared off only once, on Thanksgiving Day 1982. The men’s basketball teams have only played a single game, in Greensboro in 1969. The women’s basketball teams met for the first and last time in Chapel Hill in 1990. UNC won each matchup. That’s it.

So why are these two polar opposites united by one single, weird-ass song? Which version came first? What do the lyrics even mean? And who came up with it? There is a tiny bit of easy-to-find information about the song’s origins. But a lot of it ignores the story of the man who brought the song to thousands of students and alumni. He was a decorated World War II veteran. A musician. An actor. A fencer. A swinger. A writer of lesbian pulp fiction. A man who was drugged with LSD (maybe not exactly against his will) by a CIA agent. His story unlocks the key to the whole mystery. The most popular thing he ever created may have been one of the least interesting things about him.

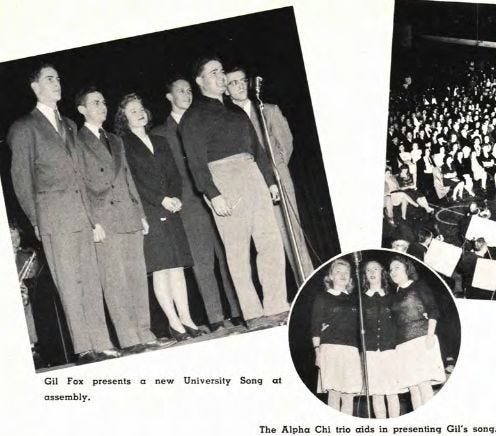

First off, there’s not a lot of easily Googleable detail online about the song’s origins at UNC. Bowling Green, at least, gives up a name and a year. “Gil Fox, an Air Force bombardier in World War II stationed in Italy, brought a loose translation of a Zulu war chant back with him,” says a description in a sports media guide, “and since its introduction in 1946 to a campus spirit assembly, it has kept its place in BGSU history.”

Well, um, it’s not exactly a Zulu war chant. “This prince of marching songs appears to be a relic of the Zulu War,” says a 1928 Oxford Song Book description of a tune entitled “The Swazi Warrior.” It was sung by British non-commissioned officers while they were deployed to colonize South Africa in the late 19th century. The rhythm is almost identical to Ay Ziggy Zoomba. The melody is pretty close. The words are different: “Ikama zeem-a zeem-a Rinktum, ikama zeem-a zeem-a zee.” The refrain is clearly in English, though: “Hold him down, the Swazi warrior, hold him down, the Swazi king.” Some Australian researchers, looking at the impact of music in spreading both multiculturalism and colonialism, described it this way:

This is, in fact, a British Army adaptation of indigenous materials turned into a marching song with text about holding down and trampling over another people, whose cultural gestures were stolen to create it. The Swazi Warrior is a patronising song about the suppression of Africans by British forces as they imposed colonial rule in South Africa.

That sort of thing didn’t give anyone pause in the early 20th century, and the song spread in South Africa and England. Boy Scouts made it into a campfire song (The Scouts’ founder, Robert Baden-Powell, had served as a soldier in South Africa4). Soccer fans chanted it at games. And South African soldiers brought it back to the front lines as a marching tune during World War II. The words, like in a game of telephone, would slightly change as the song traveled around. It’s not exactly like “Ay Ziggy Zoomba,” but it’s close. One kids’ version of the song is entitled “Izika zumba.” There’s a consensus that the “Zulu” words were just filler and mostly gibberish, sort of like fa la la la las in Deck the Halls.

Right after the war, the song made a big jump to the United States. At the end of World War II, an Afrikaner singer named Josef Marais released a set of records purporting to be South African folk tunes. “The Zulu Warrior” was one of them.

Josef Marais and his wife (and singing partner) Miranda went on tour around the country with that and other songs, and even sang “The Zulu Warrior” in a feature film, “Rope of Sand,” in 1949. The album it appeared on, “Songs of the South African Veld Vol. 1,” was released in late 1946. But it was months before, in January, when a sophomore named Gil Fox got up at a college assembly in Bowling Green and sang a new song that he’d heard during his time in the service. A song that would become Ay Ziggy Zoomba.

It was being hyped up even before its first big performance. “It isn't often that a student takes the initiative in writing school songs,” said a 1946 editorial in Bowling Green’s student newspaper, which also asked whether the new song should replace the school’s alma mater. It didn’t, but the song stuck, and it’s only grown in popularity in the nearly 80 years since its debut on campus.

A few months after Gil Fox debuted his song at Bowling Green, Norm Sper showed up for his freshman year at UNC. Sper was born in Los Angeles, the son of a syndicated sportswriter and a Vaudeville star5. Will Rogers was his godfather. Sper grew up in Hollywood, and became such a good swimmer and diver that he was featured as a future Olympian in a national newsreel at age 11. He never actually got to compete in the games—World War II cancelled the 1940 and 1944 Olympics. Instead, Sper served in the Army’s Special Services for three years, performing in shows and diving displays. At one point, he put on an exhibition with Esther Williams and Johnny Weissmuller to raise $26 million for war bonds.

After the war, Sper turned down an appointment to the Naval Academy to enroll at UNC at age 21. He became an All-American swimmer and diver, set several NCAA records, and helped Carolina win four Southern Conference championships.

Despite all of that, Sper’s greatest legacy at Carolina was that of a hype man. Sper was a dramatic arts major who dreamed of Broadway, and had experience in summer stock and radio dramas. He was, like his mother, a performer, and his fellow students elected him head cheerleader in 1948 and 1949. He cheered on Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice in three bowl games. He’s credited with creating the Victory Bell that goes to the yearly winner of the UNC-Duke football game (Sper got the Southern Railway to give him an old bell off of a steam train and a Duke cheerleader mounted it on a cart). He’s also credited with bringing card stunts to the East Coast. At his direction, students at Kenan Stadium would hold up colored pieces of cardboard to form shapes in the stands. (The cardboard club went away for good in 1987 after students started launching the cards toward the field at the end of games).

Sper also riled up students at pep rallies. He led his fellow cheerleaders in song. And so, the night before UNC played Wake Forest in October 1949, Sper led his fellow cheerleaders in a new tune: “Roll ‘Em Down, You Tar Heel Warriors.” It’s the first known reference to the song that would become “Aye! Zigga Zoomba” at UNC, and in the years since, the UNC alumni magazine has given Sper credit for coming up with the song.6

After his graduation in 1950, Sper got married to one of his UNC classmates, and moved to New York City where both joined an “Aquashow.” In 1952, Sper moved back out west, first helping his father in television production before launching several successful businesses, and eventually producing a worldwide radio ministry with the pastor at his church. He retired in 1989, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease in 1992, but stayed active until just before his death in 2011 at age 85. “Don’t be surprised if he’s still whistling and even leading heaven’s cheering section praising God,” read his obituary.

That life could not have been more different than that of Gil Fox.

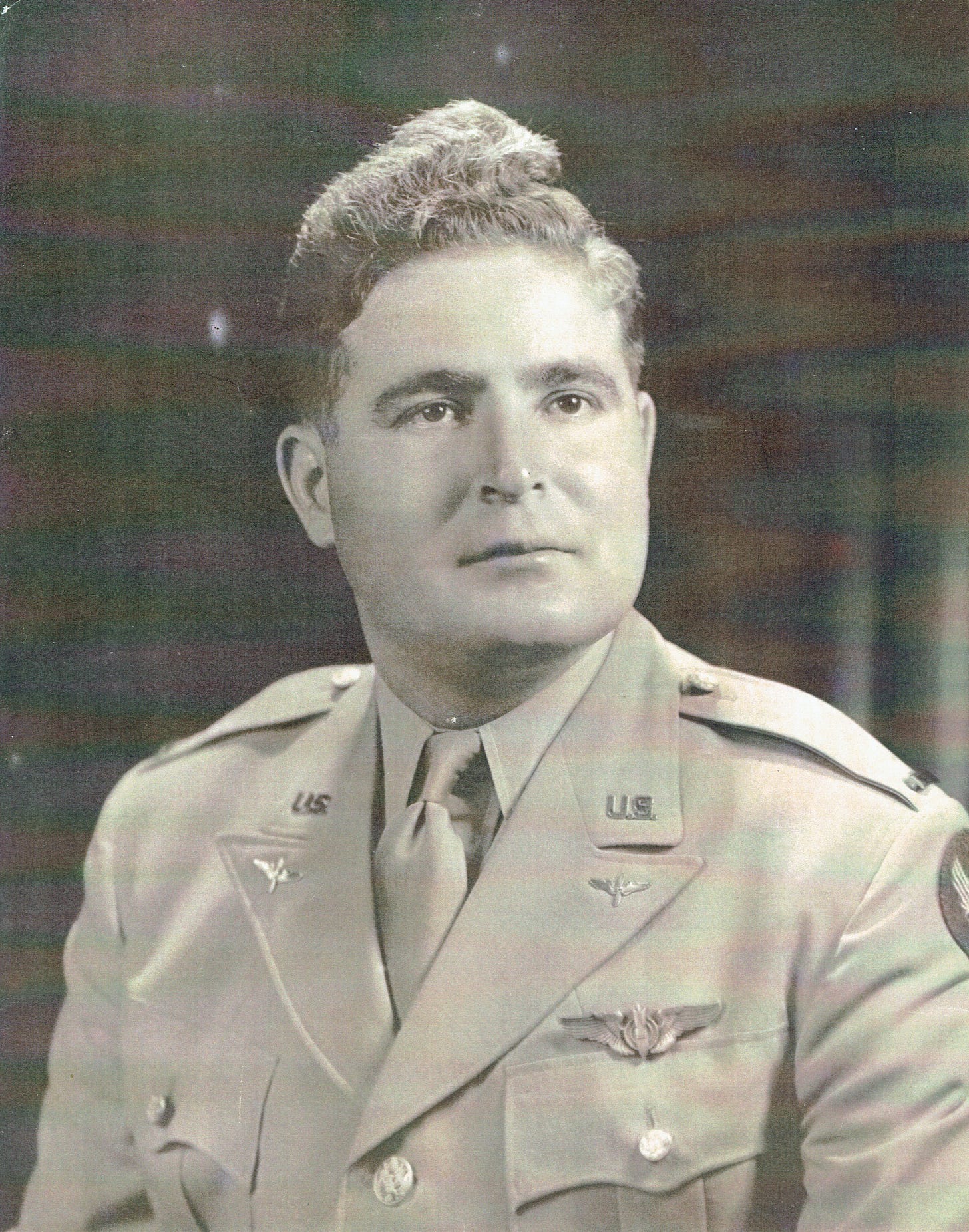

Fox was born in Connecticut in 1917. From an early age he was a good student, and his math skills earned him a scholarship to Columbia. He enrolled at Louisiana Tech instead, but when World War II broke out, Fox joined the Army Air Corps, and served as a first lieutenant bombardier. His missions over Italy and Southern France earned him several medals and a Purple Heart.

At some point, performing became Fox’s focus. He’d been in plays in Connecticut and Louisiana, along with theatricals during his time in the Army (vis-à-vis Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye in “White Christmas”). After he got out of the service, Fox enrolled at Bowling Green, decided to major in music, and landed the part of Teddy Brewster in a student production of “Arsenic and Old Lace.” He played the piano. He worked on the yearbook. He was a gossip columnist in the student newspaper under the name “The Mark of Zorro” (Zorro is Spanish for “fox”). He was also an inaugural member of a secret school spirit society called SICSIC, which still exists today.

During his junior year, he fell in love with a young woman who’d just transferred to Bowling Green from Millsaps College in Mississippi. She’d been a beauty queen down there, and was voted the prettiest girl on campus after she arrived in Ohio. They got married in 1947, not long after she graduated, and the newlyweds went back to Bowling Green after their summer honeymoon. Gil, who was ten years older than his bride, still had one more year to go before his graduation with honors in 1948. It seemed, from afar, that the two were living an idyllic, All-American life. But Fox did not want a clean-cut existence. “Gil wasn’t your typical trombone teacher,” writes the journalist and author Douglas Valentine. “His real interest was in writing about sexual deviation, especially lesbians and fetishes.”

In 1950, Fox and his wife moved to in New York’s Greenwich Village, an increasingly bohemian enclave that was home to avant-garde writers, poets, playwrights, and artists who were looking to escape the stringent social conformity and sexual mores of the day. Not long after he arrived, Fox met an artist named John Willie, who put out a magazine named Bizarre and specialized in drawing women in high heels. The two hit it off, and Fox agreed to write softcore pornographic novels for Willie’s Woodford Press. Soon after, Fox set out on his own and formed Vixen Press, which he ran out of his apartment at 125 Christopher Street (which is said to be the inspiration for the apartment in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window”).

Fox was prolific, often turning out a book a month. He had plenty of source material: Fox said his wife was bisexual, the two were swingers, and met plenty of couples in Greenwich Village who were down for a foursome. Lynn Munroe, a book collector, interviewed Fox later in life, and asked him about other inspirations for his books. “I would watch old movies and imagine the man and woman as two women and re-imagine it as a lesbian scene,” Fox told Munroe. “I’d pull a whole scene from the Late Show and write it down and put it in a box. Then I’d pull ideas from the box when writing a book.”

Fox always used a pen name, like Dallas Mayo, Kimberly Kemp, or Paul V. Russo.7 In the 1960s, he latched on to legendary pulp fiction publisher Midwood Books and began writing for them. Before, Fox had made roughly a dollar a page. At Midwood, he was paid between $500 and $1,000 per novel, sometimes with royalties. Even though he could crank out books rather quickly, he was serious about his craft. He told Munroe that a fellow erotic writer wrote “absolute drivel.” He described himself as the best writer at Midwood. He got mad when the publisher would rename his books. “They always changed my title to some awful title,” he told Munroe. His house was full of paperbacks with the covers torn off, with his own titles handwritten on the first page.

Fox worked hard, and he played hard. Early on, John Willie had introduced the Foxes to another Greenwich Village couple, George and Tine White. They all hit it off. One night in November 1952, the Whites had the Foxes and their friends over to their apartment, and things went sideways. “We were all boozing and smoking pot in those days, including George,” Fox later told journalist Douglas Valentine. “One night George gave us LSD. He slipped it to us secretly.” Afterward, the Foxes and their friends walked around the snowy Village. “We stopped the car on Cornelius Street and the snow was red and green and blue–a thousand beautiful colors–and we were dancing in the street,” Fox recalled. They began to trip. Badly.

At first, they didn’t know that White had given them LSD. Later, when the Foxes found out, that didn’t stop them from hanging out. “I was angry at George for that,” Fox told Valentine. “It turned out to be a bad thing to do to people, but we didn’t realize it at the time.”

White, it turned out, was a CIA agent, and he wasn’t just giving out LSD for fun. The CIA was interested in mind control drugs, and had (wrongly) heard that the Soviets were stockpiling LSD for that use. To catch up, the CIA decided to test LSD’s effects to see if it might be useful for them. Early academic studies eventually gave way to clandestine testing that the CIA called Operation Midnight Climax. White, who’d moved to Greenwich Village to make inroads in the seedier sides of that community, decided to run his own LSD experiments on the people he met. He’d passed himself off as an artist and sailor, and in 1953, he used CIA money to rent a new apartment on Bedford Street that was set up to watch and record people who’d been drugged. Fox’s wife, an artist, painted murals on the walls to make it feel more bohemian. “We knew he was a federal narcotic agent and was giving people LSD,” Fox told Valentine. “He would invite people to the Bedford pad, dose them with LSD, and then take photographs of them through a two-way mirror. But I never got into it. We weren’t interested in that aspect of his life. He wanted to keep that aspect of his lifestyle secret. At the time LSD was great fun, that’s all. Then sub-agent Olson walked out the window, and that’s when the shit hit the fan.”

In November 1953, Frank Olson, a Department of Defense employee, ran through a tenth floor window at a nearby hotel and fell to his death two days after White had secretly dosed him with LSD. By 1954, White had left New York and continued his secret LSD experiment on the west coast.

After the Whites left, the Foxes stayed. Their family grew, first with a son, and then a daughter. Then, other things began to shift for Gil. His marriage broke up around 1960.8 Gil, though, continued to write paperback pulp fiction that often went on sale in sleazy Times Square bookstores. His lesbian-themed books, which were aimed at men, also gained a following in New York’s then-underground LGBTQ community. In a twist of fate, Fox happened to be hanging out in The Lion’s Head, which he called “a gathering place for gay men and dirty book writers,” when the 1969 Stonewall Uprising began.

Not long after that, the adult book industry went through a major change. Supreme Court decisions that loosened up the definition of obscenity and pornography made the sleazy paperbacks of the 1960s (which read like today’s drugstore romance novels) seem tame in the 1970s. “The adult book business collapsed when the Mafia came in and took over the bookstores and said they would only sell books by their own publishers,” Fox told Munroe. “And they started printing and selling absolute garbage.” During his career, Fox wrote more than 100 adult books, and they stood out in a decidedly non-literary genre. His work still has dedicated fans, according to Munroe and others. “I'm a big fan of Gilbert Fox,” one person wrote to the curator of a Lesbian Pulp Fiction Collection at Mount Saint Vincent University. “There was no greater than him in the ability of erotic literary expression when it came to lesbian relationships.”

Eventually, Fox left Greenwich Village for Northern California, where was active as an actor in community theater. He played piano. He was open to interviewers who described as “cantankerous.” And he continued to write. “Some of my stuff is still pretty hot,” he told Munroe later in his life.

Fox was incredibly open with interviewers, but not with his family. Gil’s son Jon remembers his father as great storyteller who loved telling jokes. He helped out with Jon’s school assignments, and was a stickler about grammar and spelling. He didn’t talk much about World War II, even when Jon was making a model of Gil’s wartime bomber, the B-17. He also didn’t elaborate on his wild times in Greenwich Village. Jon remembers George White, but only as a family friend. He doesn’t have much to say about his father’s books.

Jon Fox said his mother and father’s divorce was messy, and he and his sister mostly blamed Gil for the problems. It wasn’t until later in life when Jon reconnected with his father, and his memories mostly center on Gil watching television. “He was a very private person,” Jon tells me.

Gilbert Fox died in 2004. His obituary mentions his adult books. His family. His musicality. And his authorship of the Bowling Green fight song. He seemed to be grumpy about the song he’d popularized. Jon’s sister Heidi once said that Bowling Green wanted to bring Gil back to campus to honor him for Ay Ziggy Zoomba. “No way,” Gil told her. “Not interested.”

So after all of that, there’s still one question hanging out there. What’s the connection between UNC and Bowling Green? Why do those two schools share this one strange song?

The connection seems to have been Gil Fox. After he graduated from Bowling Green, he enrolled in graduate school. At the University of North Carolina.

This wasn’t as random as it seems. Fox’s wife had grown up in Chapel Hill, where her father was a businessman9. She still had family there. So in 1948, the newlyweds moved from northwest Ohio to an apartment on Ransom Street, not far from campus. Fox continued his studies. His wife worked as a dental assistant. Fox, who was also a fencer, joined UNC’s brand new club team and later became a coach. He got to know a drama professor and his wife well enough that the couple came to visit the Foxes a few years later in New York City (and subsequently got drugged by George White on that snowy November night in 1952).

It’s unclear whether Fox got to know Norm Sper during Fox’s two years in Chapel Hill. And it’s entirely possible that Sper came up with the song all on his own, based on a song that was known nationwide (After all, when Aye! Zigga Zoomba first shows up in the Carolina Handbook in 1950, the instructions are to sing it to the tune of “The Zulu Warrior”). Sper himself, in an interview 50 years afterward, told the now-disappeared ramfanatic.com that he thought he might have heard the tune at UCLA games as a kid, although I couldn’t find any record that UCLA ever used it. There’s a lot of circumstantial evidence here. But it’s also quite likely that this could all be a fantastic coincidence.

I turned over every last stone. I looked at census records and archival documents. I scanned old newspapers. Made calls to historians. I asked Douglas Valentine and Lynn Munroe if there were other parts of their interviews that didn’t make it into their stories (there weren’t). I tried, in vain, to see if Gil Fox had somehow convinced a cheerleader, a musician, or anyone else at UNC that they should start using Ay Ziggy Zoomba as a pep song. I looked for a concrete connection between Fox and Norm Sper. They were both performers. They both knew the ins and outs of school spirit. But I found no smoking gun. The closest I came was an issue of the Carolina Alumni Review from 1949. An article about Norm Sper’s cheerleading, swimming, and diving, performing arts background and Broadway dreams appeared on page 98. Right next to it, on page 99, is a short item about fencing that includes Gil Fox’s name.

Still though, it’s amazing how time can strip away meaning and context, especially from music. For almost eighty years, students and alumni of two universities have been joyfully and naively singing a catchy song that was born as a colonialist war chant and was popularized by two well-known students: one who explored sexuality by writing paperback novels and one who channeled his charisma into a successful career in business and in church. The song’s melody still gets people fired up, even though most of its lyrics are complete gibberish.

Ay Ziggy Zoomba means nothing. And yet, it means so much.

Ay Ziggy Zoomba is probably more popular than Bowling Green’s first “official” fight song, “Forward Falcons,” which was written by two BGSU faculty members in 1948, two years after Ay Ziggy Zoomba made its debut. The student senate officially made it a second fight song in 2013.

They weren’t the only schools ever to use it. A single blog post says the song was used for a time at Guilford College in Greensboro. And Jim Harbaugh introduced it to Stanford as a football coach there, mostly because he’d grown up hearing his dad Jack, a Bowling Green alum, singing it. "There was a year or two in there when I brought the Ay Ziggy Zoomba, I commandeered it and brought it to Stanford," Harbaugh told Yahoo! Sports. "It didn't really take hold, they're not still singing it. It didn't last the whole four years I was there, but I tried it." It’s possible that other schools also used the song for a while, but it’s extremely hard to find records of it.

I can’t drag Bowling Green that much. I went to Buckeye Boys State as a rising high school senior and was elected to a city council position there! I got a cool t-shirt out of it.

A correction and clarification: I’d originally stated that Robert Baden-Powell served in the Zulu War, which came later. He was in South Africa among the Zulu people earlier than that. The clarification is that I’m wildly understating how popular this song was among Boy Scouts and summer campers. It’s likely that far more people in North Carolina know it as something they sang as kids as opposed to something they heard at a UNC game.

Norm Sr. also has a wild story. In 1915, he showed up in the New York Times and told a story about how he’d gone to Belgium during World War I, got inside the German lines, took a bunch of German posters, and became the first person to bring them back to America in an effort to tell spread awareness of the war. He was 19!

The Carolina Alumni Review from 2002 is also significant for being one of the few printed reports where UNC acknowledges that Bowling Green also uses the song, and notes that BSGU had been using the tune since 1928 (the same year the song appeared in the Oxford Song Book), but added words in the 1940s. Bowling Green, for its part, seems to have never officially acknowledged UNC’s use of the song, although grumpy message board posters have occasionally gone out of their way to brag that Bowling Green was using it first.

One really confusing side note: Around the same time, there was another man in New York City who was also named Gilbert Theodore Fox! He was two years older than this story’s Gil Fox, and became a well-known cartoonist. Gil Fox (the adult author) and Gill Fox (the cartoonist) even died in the same year: 2004. I say this because I’d be looking up old stories or blogs or documents, and get excited that I’d found something new, only to discover that I’d once again been reading about the wrong Gilbert Fox. I’m just saying all this because I want you to sorry for me, I guess.

I intentionally didn’t name Gil Fox’s wife in this story, mostly because she seemed to have moved on from that period in her life, and she didn’t publicly get to tell her side of the story like Gil did. She became successful and well-known in her own right, albeit under a different name. She left New York, remarried, earned her doctorate degree, and became an author, therapist, and researcher whose work was praised and presented in books and on television.

That family was originally from Sanford, North Carolina, moved to Chapel Hill, and eventually ended up in Jackson, Mississippi. Gil Fox’s father-in-law was in the oil business, and when his wife died in the mid-1960s, he quickly remarried. The marriage, uh, didn’t last. Fourteen months later, Gil’s father-in-law was found naked and dead from 17 stab wounds on the floor of his house in Jackson. His new wife went to prison for his murder.

Jeremy, I am always impressed by your research but you have outdone yourself this time! What a fascinating story. My UNC degree is in broadcast journalism, so I can read between the lines of your hard work. And as a former Carolina cheerleader, you have solved a mystery I've wondered about since I was a teenager. That is one strange song, but the back story is even better. Thank you!

This is wild. My FIL asked me about this song and where it came from about 4 years ago. I did just enough research to say that we (UNC) probably stole it from Bowling Green. You've done an extraordinarily good job of getting all the context around it.

I don't know if you went this far, but you might see if Wilson Library has any playbills from Playmakers Theater. They certainly have images from a 1948 production, which might show the two together on stage. https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/catalog?group=true&group=true&search_field=all_fields&q=Playmakers+Production%2C+Circa+1948

That's really the only thing I can think of that might tie them together. Weird side note: this was the same era that a mentor of mine, John Sanders, was at UNC. It's kind of crazy to imagine him on campus at the same time as these two.