Not long after I started at Our State, I took a day-long, 402 mile road trip through Eastern North Carolina, mostly because I hadn’t been out there too much and wanted to see a lot in a short amount of time. Over the course of a very long day in 2015, I found the hidden Cherry Hospital cemetery in Goldsboro, encountered the decaying fuselage of a private jet on a loading dock in Tarboro, met baby cows and had dessert at the Simply Natural Creamery in Ormondsville (“Your ice cream was grass yesterday!” the owner told me), and stopped in at the Nahunta Pork Center, which a supermarket that only contains pig stuff.

On the way home, I made a detour that I hadn’t planned on. I was near Greenville, and saw a few signs for Farmville. I got excited. I was a fan of Duck-Rabbit beer, and knew that it was brewed somewhere in town. I just didn’t know where.

Google Maps led me down a few side streets until I found it. I don’t know what I expected, exactly, but I didn’t expect a few metal-sided buildings hidden behind an old tobacco warehouse. It really, really didn’t look like much. Also, the taproom was closed that day. But I knew, somehow, that fate had led me there. I’d been curious about this place for so long. At least I got to see it.

I haven’t had a Duck-Rabbit beer in a while. They’ve been hard to find at the store, and I haven’t heard much from them lately. This week I figured out why: It’s shutting down. After 21 years in business, the company abruptly closed amid a Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing.

Still, Duck-Rabbit occupies an interesting place in my memory. The folks there were making interesting styles of beer in North Carolina at a time when few others were. You could easily find it in stores across the state, but they truly were a local product. And for me, they turned a small, out-of-the-way spot into an exotic place. I remember driving out of Farmville, past the empty storefronts, the wide porches, and the open fields. There wasn’t much else to see.

I swore that someday, I’d come back.

A lot of craft breweries are struggling right now. Sure, Charlotte and Raleigh still have plenty, but for a while, it seemed like beer makers were setting up in every street corner and small town across North Carolina. Nearly ten years ago on a trip up to the foothills, I showed up in Granite Falls, a city of fewer than 5,000 people. It had a brewery! The owners, who were Southern Baptists, were once told by folks in town that brewing beer would punch their ticket to hell. That didn’t stop Granite Falls Brewing from opening in 2013. Folks liked it. The food was good. The beer won awards. Some 40 people got jobs in a town that desperately needed them. People began to make road trips to Granite Falls. When I stopped in, I talked to the mayor, who told me it had a different feel than a bar. It was a community hangout, and not really a place to get blitzed. The proof, the mayor said, was in his presence. He was there all the time, and he didn’t even drink.

This was a bit of a small town vibe shift, one that North Carolina’s original craft brewer, Uli Bennewitz, saw coming a long time ago. A 2005 North Carolina law that allowed brewers to create higher-alcohol beers helped. But Bennewitz felt like there was a bigger movement toward local products after the 2008 economic crash. His theory: People felt like global forces had dragged them down. “Suddenly, people were looking for local,” he told me in 2017. “The brewpub became what it used to be in England: The local meeting spot. It’s not a franchise. The old folks meet at McDonald’s for coffee in the morning. But the young kids meet at the brewpub in the evening. And the guy who brews the beer joins in.” That didn’t mean that Bennewitz didn’t have a fight on his hands early on. When he opened Weeping Radish restaurant and brewery in 1986, the conservative community of Manteo wasn’t all that thrilled to see him set up shop. That’s what eventually led him to move a few miles out of town in 2005. But in the end, local spots, like coffee shops, restaurants, bakers, and especially breweries, would be seen as the ways to bring small towns back. “Back in 1986, they only thought the churches would sustain a community,” Bennewitz told me. “The younger generation said: Never mind the church. Let’s meet around a beer.”

Movements can’t last forever. Last year, for the first time, more craft breweries closed than opened. People are drinking less beer than they used to, and the cost of everything, including ingredients, is going up. More than a half-dozen breweries went under in the Charlotte area last year. Three closed in Raleigh. Granite Falls Brewing shut down last year. Bennewitz sold Weeping Radish to new owners in 2021. Since then, it’s shut down its brewery and restaurant out in Grandy, and moved the actual brewing of its beer to Raleigh. It now has a taproom inside the Firetender restaurant in Manteo.

Now, add Duck-Rabbit to that list. According to a bankruptcy filing, the brewery only had about $282,588.50 in assets, most of it being its brewing equipment. At the end, there was only around $5,000 in the brewery’s cash reserves and checking account. Its liabilities were more than $1 million. It was on the hook for hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes and small business loans. Revenue was declining. In 2023, Duck-Rabbit brought in around $577,000 in 2023, which dropped down to about $427,000 last year. At one point the owner, Paul Philippon, appears to have loaned Duck-Rabbit nearly $30,000 to keep it going.

A bankruptcy filing is a fairly sterile document, and it doesn’t paint a complete picture of what happened. Philippon himself hasn’t elaborated on the closure past a Facebook post where he said “I know that this is the right decision.” But the end of Duck-Rabbit ends a long journey for him, one that started when he was a philosophy professor at Eastern Michigan University looking for a career change. He went from homebrewing to working at a brew pub in Cincinnati, then moved on to bigger production facilities in Louisville and eventually North Carolina. He decided to go it alone in 2004, and opened Duck-Rabbit in Farmville because he could buy his own land with room to expand. “If what I wanted was to make a bunch of money, I’d go be a banker,” he told Beer Advocate in 2008. “What I want is to brew beer I’m proud of and that I love. So, since it’s my company, that’s what I do.” People told him that folks in the hot South wouldn’t take to dark beers, and yet the Milk Stout was always his top seller.

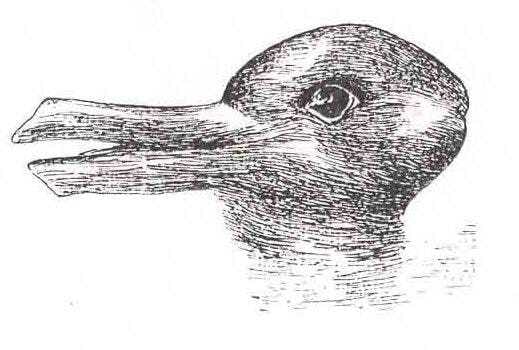

For what it’s worth, there was a lot of hidden philosophy infused at Duck-Rabbit. The logo, which looks like either a duck or a rabbit, was based on a drawing from one of Philippon’s favorite books: “Philosophical Investigations” by Ludwig Wittgenstein. And the company that Philippon originally formed to buy the brewery’s property in Farmville in 2004 was Gavagai, LLC. “Gavagai” refers to another philosophy thought experiment, in which a linguist has to figure out what “gavagai” means after hearing it spoken by a speaker of an unknown native language upon seeing a rabbit.

Being in the beer business was both scary and exciting, he said, and he sounded a little less philosophical in talking about it. “All the risk is on your shoulders,” he told Beer Advocate in 2008. “If this doesn’t go, I’m in debt forever and ever and ever. I’ll never make enough money to pay off these debts. So, yeah, that’s scary, but I felt like I had something to contribute to beer culture, and I always wanted the opportunity to try to make that happen.”

Philippon set out to make beer. But he—maybe inadvertently—did something else. He introduced tiny little Farmville to a lot of people who might not otherwise know it existed, including me.

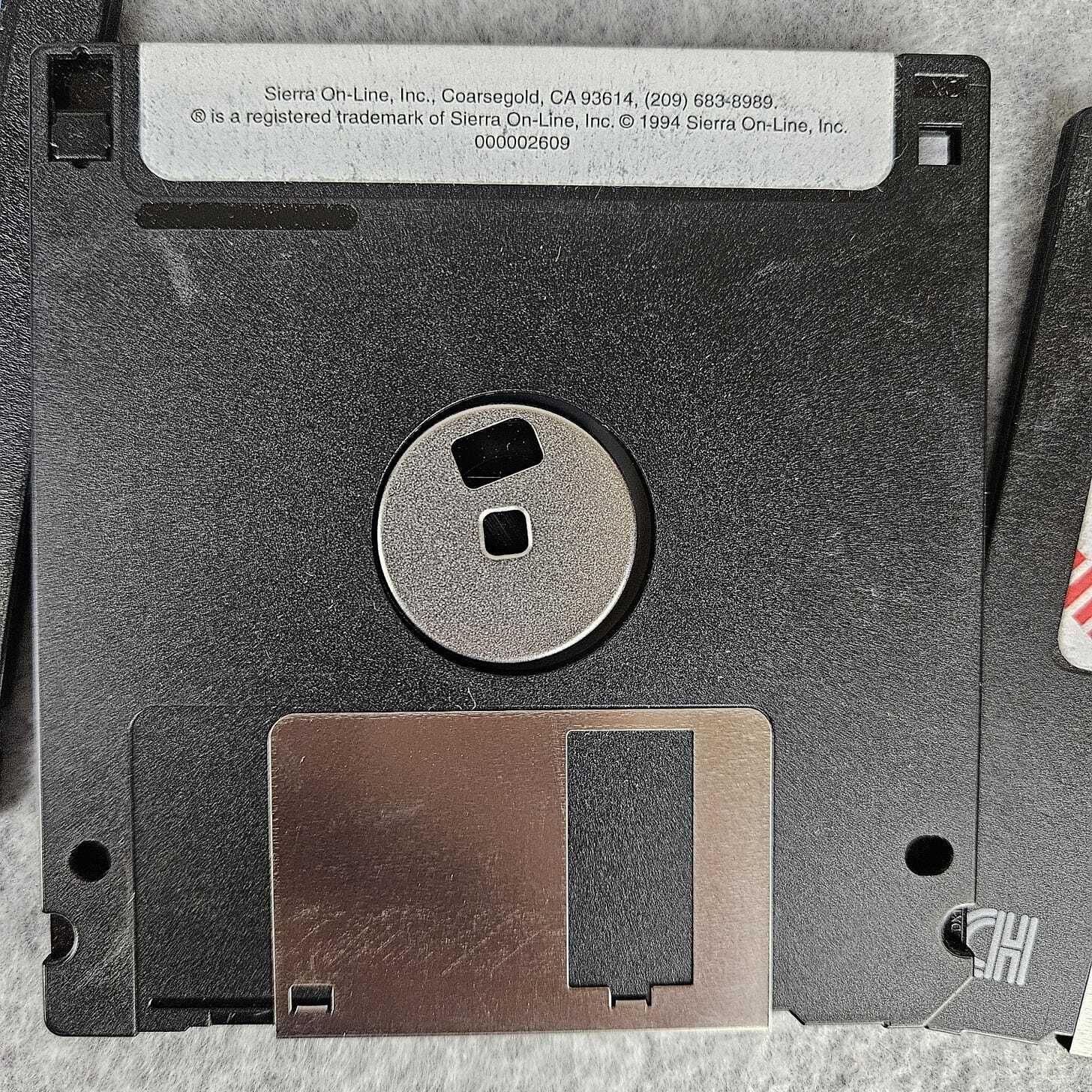

Quick detour: Back when I was a teenager, my family and I took a three-week road trip out west. As we drove through a particularly mountainous stretch of two-lane road in California, we passed through a small town called Coarsegold. I saw the sign and immediately perked up. I told my mom and dad that we had to stop. They were confused, but I wasn’t. Some of my favorite computer games, the Space Quest series in particular, were made by a company called Sierra On-Line. A few places—floppy discs, instruction manuals, and boxes—listed the address of its headquarters: Coarsegold, California.

I insisted that we immediately stop our trip and find Sierra On-Line. My parents humored me, and we stopped at a few places to ask where the headquarters might be. And that’s how, in the mid-90s, I showed up at the front door of my favorite video game company and asked for a tour. The slightly confused but friendly employees showed me around what looked like a plain-old office building, gave some tiny bit of Sierra swag that was lying around, and after a little bit, sent us on our way. I left, feeling like I’d just discovered Atlantis. I couldn’t wait to tell the kids on my street that I’d gone to the place that had given us Leisure Suit Larry (which was strictly forbidden at home).

I used to have that excited road-tripping feeling quite a bit. Days before we drove through Coarsegold, we passed through Coolidge, Kansas (which was the hometown of Cousin Eddie in National Lampoon’s “Vacation”). A few years later, on the way back to Ohio from Hilton Head, I saw a sign for Wake Forest University and demanded that my parents drive 45 minutes out of the way to get me a hat. (I’d like to think of this as foreshadowing, since I got a job at Wake 25 years later). But over time, my process of discovery has changed. Stumbling upon things is more difficult. Google Maps and Street View allow you to visit faraway places from your phone. I hadn’t truly stumbled into a completely unknown place in some time.

And then, in 2015, I saw a sign for Farmville.

Three year later, I was back in the area to check out the Shad Festival in Grifton (along with its neighboring suburb, Tick Bite), and I saw the same signs I’d seen two years before. This time, Duck-Rabbit was open. A few folks were lingering on the picnic tables outside. The beer inside the tiny taproom was tasty. The bartender reminded me that buying directly from him meant that Duck-Rabbit got to keep all of the profits instead of sharing them with a distributor. Hence, I left with several six packs of exotic dark beers that I’d never seen in stores before. I went home happy. After I got back, I told everybody that I’d gone to the out-of-the-way place that gave us great beer. If I’m being honest, I wanted them to be a little jealous.

I haven’t been back since then. I’m happy that I got to go. I’m sad that it’s gone. I’m grateful for all of the beer. And I’m glad the Duck-Rabbit put Farmville on the map. I’ll remember the excitement of that little discovery nine years ago, and the lessons that came from it: Small places are still important, and the stickiest memories are the ones you don’t set out to make.