Sometimes the dictionary gets you all riled up:

No need to debunk this. The word ‘bunk’ is a shortened form of ‘bunkum,’ which came from Buncombe County, North Carolina (where Asheville is located). In 1820, the congressman from Buncombe County gave an intentionally boring and long-winded speech to Congress…

He only made it to appease the voters of Buncombe County. ‘Buncombe’ and ‘bunkum’ quickly caught on as a name for empty political nonsense. It was soon broadened to include any kind of empty or insincere talk or action. In time it was shortened to the more emphatic ‘bunk.’

I have heard this before. And look, I know this is the Merriam-Webster Dictionary we’re talking about here. It’s literally the place you go to fact-check the meaning of words like Australopithecus and yeet. Still, though, who will watch the grammatical watchmen if not me, a guy who makes a lot of typos whilst writing about North Carolina ephemera? Trust but verify, dictionary. Trust but verify.

And so, here is the story of a Revolutionary War veteran turned congressman who got meme’d in the year 1820. In fact, he got meme’d so hard that he accidentally created a term that’s entered the modern lexicon and has never quite gone away.

The Old Oil Jug and the 19th century Attention Economy

Felix Walker grew up in a lot of places that technically don’t exist anymore. He was born in 1753 on the banks of the Potomac River in Hampshire County, Virginia, which today is part of West Virginia. When he was still a kid, his family moved to Tryon County, North Carolina, which is no longer on the map (It was split into Lincoln and Rutherford Counties in 1779). Walker later became a trail blazer with Daniel Boone, and helped open the Wilderness Road into Kentucky in 1775. He fought against Native Americans on the frontier, and then served in the Revolutionary War. Afterward, he became a county clerk in Rutherford County, and farmed and traded land in Haywood County. He seemed to be fairly well respected, and in 1816, he was elected to the first of his three terms representing several western North Carolina counties—including Buncombe—in Congress. By one account, he won “on account of his patriotism, generosity, and hospitality, rather than for his talents.” His nickname was “Old Oil Jug.” Just putting that out there.

During Walker’s time in Congress, representatives were locked in a debate over slavery and how the territory of Missouri should be admitted to the Union. A proposal to make Missouri a free state came from a New York representative in early 1819, and it proved to be so controversial that it ended a quaintly-named period known as the “Era of Good Feelings.” For months, lawmakers were yelling at each other. They were trying to protect their own political power. The South wanted to expand slavery. The North wanted to stop it.

It took a year, but Congress finally came up with the Missouri Compromise: The United States would admit Missouri as a slave state, as long as it also admitted Maine as a free state.

On February 28, 1820, nearly everybody’s mind was made up, but the final vote hadn’t been taken yet. Not long after the House of Representatives was called into session, a congressman from Massachusetts named Mark Hill rose to say: We should stop talking about this bill. Everyone pretty much knows how they’re going to vote! Let’s do it already! But another congressman, William Lowndes of South Carolina, suggested that it might be a good idea to give two or three more people a final chance to speak. Hill agreed, and the speeches started.

According to the Annals of Congress, a guy from South Carolina went first, and spoke “at considerable length.” A representative from Missouri went next, and spoke for a very long time. How long? Who knows! But the proceedings take up a whopping 47 pages of text in the Annals. That’s a lot of words!

After this long back and forth, a Congressman from Maryland got up. Look, he said, a lot of the people I represent don’t agree with my stance. It would probably be a good idea if I made a speech to explain myself to them. But! We’re all weary of this debate! Everybody’s mind is made up! This has gone on long enough! Could everybody please please PLEASE just knock it off?

And it was at that moment, after a year of shouting, after several weeks worth of speeches, and after a bruising day in the chamber, that something stirred inside 67-year-old Felix Walker. I know what the guy from Maryland just said, he must have thought. But I’m built different.

Walker stood up.

I too must speak, he stated.

Mr. WALKER, of North Carolina, rose then to address the Committee on the question; but the question was called for so clamorously and so perseveringly that Mr. W. could proceed no farther than to move that the Committee rise. The Committee refused to rise, by almost a unanimous vote.

If you don’t speak Robert’s Rules of Order, what that means is this: Walker’s fellow congressmen told him to shut the hell up. They really, really didn’t want to suffer through another speech.

To his credit, Walker wasn’t the only one who had terrible timing. Right after he was shouted down, a guy from Ohio also rose to speak. His colleagues didn’t want to hear from him either.

Not long after that, at five o’clock, the whole thing ended. Congress voted, the bill passed, and President James Monroe signed the Missouri Compromise into law a few days later on March 6.

A Really Old Story that’s Hard to Debunk

But back to Walker. Did he actually deliver the speech? Unclear! One account said he actually did speak, despite everyone around him yelling something to the effect of SHUT UP OLD MAN. Another telling said he started his speech but couldn’t finish because his colleagues were loudly shouting him down. And another account said Walker was rising to speak about Revolutionary War pensions, not Missouri. Look, folks. This all happened 205 years ago. The general outline of the story is intact. But as for the details? Who really knows. Walker doesn’t mention this moment in his memoir, only noting that “in the most of the most interesting and popular discussions, I threw my mite1 on the floor,” and that Missouri became a state on his watch.

The only thing we do know is that Walker really didn’t care if his colleagues in Congress cared what he had to say. He just wanted to be on record saying … something. In an aside published in an 1860 book, “The Pictoral Field-Guide to the Revolution,” historian Benson Lossing wrote of the incident (bolding is mine):

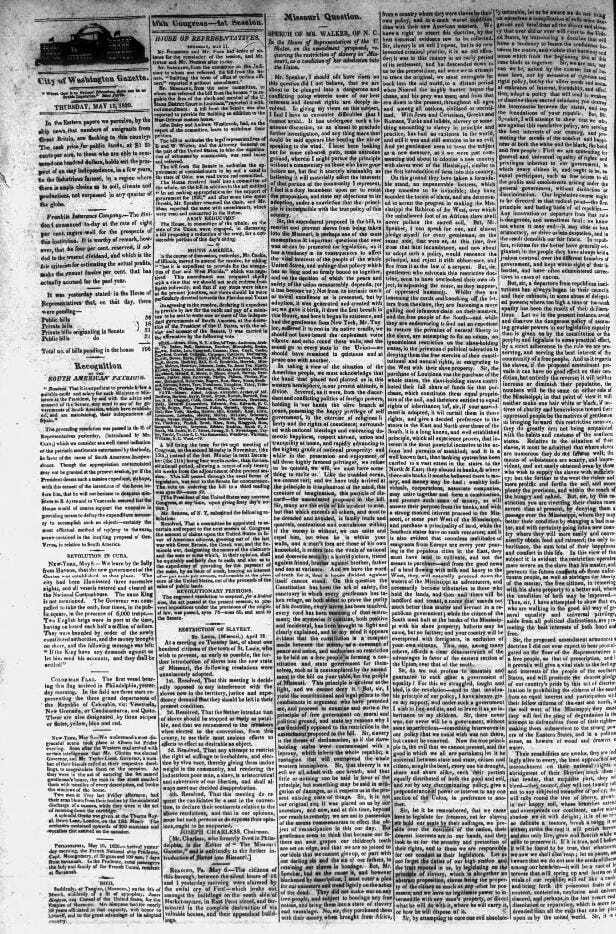

A determination not to hear him was manifested. He appealed to the late Mr. Lowndes to interpose in his behalf, intimating that he would be satisfied with the allowance of five minutes for a speech that might be published in the newspapers, and assuring him that his remarks were not intended for the House, but for Buncombe. He was gratified, and spoke under the five minutes' rule. To the astonishment of the good people of Buncombe, the speech of their representative (a curious specimen of logic and oratory) appeared in the Washington City Gazette, covering nearly a broadside of that paper. "Speaking for Buncombe" (not Bunkum) is a term often applied since to men who waste the time of legislative bodies in making speeches for the sole purpose of receiving popular applause.

If Walker just wanted to get into the paper, then mission accomplished. Months later, in May for some reason, the Gazette published Walker’s entire speech, all 4,879 words of it. Had he delivered it, it would have taken him 35 to 40 minutes to get through.

And what, exactly, was Walker trying to say? I tried to read this speech. To say that it’s meandering is an understatement. Here’s one part:

Sir, that slavery is an evil we all admit with one breath, and that little or nothing can be said in favor of the principle, but

Oh God, there’s a “but.”

something may be said in mitigation of damages.

He mentions “Nimrod the mighty hunter” as well. Nothing gets your toes a-tappin’ like a Nimrod reference.

What I think Walker was trying to say is that slavery is bad, but it’s been around a long time, and the South is already doing it, and if states want to keep doing it then that’s up to them, and that some enslaved people really like being enslaved (ew, no), and Congress shouldn’t mess with it because that could lead to a civil war (foreshadowing alert!) What Walker was saying wasn’t exactly novel for the time. He wasn’t trying to say something persuasive. He just wanted to remind voters in Buncombe County that he was in Congress doing Congress things. He was important enough to have his whole address to Congress printed in the newspaper. Even if the whole address didn’t really happen.

A Primeval Meme is Born

People saw right through it. Almost immediately, the phrase “speaking to Buncombe” entered the lexicon in Washington circles. Eight years after Walker’s speech, Niles’ Register said that “talking to Bunkum” was “an old and common saying at Washington, when a member of congress is making one of those hum-drum and unlistened to ‘long talks’ that have lately become so fashionable.” Author Thomas Chandler Haliburton wrote an entire chapter based on the word in volume two of his 1844 book “The Attaché; or, Sam Slick in England.” In it, the main character explains it this way:

I’ll tell you then, what Bunkum is. All over America, every place likes to hear of its members to Congress, and see their speeches, and if they don’t, they send a piece to the paper, enquirin’ if their member died a nateral death, or was skivered with a bowie knife, for they hante seen his speeches lately, and his friends are anxious to know his fate. Our free and enlightened citizens don’t approbate silent members; it don’t seem to them as if Squashville, or Punkinville, or Lumbertown was right represented, unless Squashville, or Punkinville, or Lumbertown, makes itself heard and known, ay, and feared too. So every feller in bounden duty, talks, and talks big too, and the smaller the State, the louder, bigger, and fiercer its members talk.

“Well, when a critter talks for talk sake, jist to have a speech in the paper to send to home, and not for any other airthly puppus but electioneering, our folks call it Bunkum.

Another book called “Bunkum” came out in 1907. The term was eventually shortened to “bunk.” In 1916, Henry Ford, speaking about living in the present, stated, “History is more or less bunk.” H.L. Mencken wrote “On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe” in the early 1920s around the same time that William Woodward wrote the novel “Bunk,” which debuted the antonym “debunk.”

Decades later, the word may have peaked when it ended up atop American society’s cultural apex: In an episode of Seinfeld:

All of this was the side effect of a bit of electioneering. So did it actually work? Sort of? Walker was re-elected to a third term in Congress in 1821, but it’s hard to know if that speech put him over the top. That election would be Walker’s last, though. He decided he was too old to run again, and was replaced two years later by the father of Zeb Vance. In 1824, Walker moved to Mississippi, where he died in 1828.

Today, a historical marker to Felix Walker stands near Maggie Valley in Haywood county, not far from his homeplace. There is no evidence that he ever resided in present-day Buncombe County. So yes, the man who dropped a Buncombe reference into the modern lexicon never even lived there. If that feels like a load of bunk, I don’t blame you.