The Legend of the North Wilkesboro Moonshine Cave

A few weeks ago, workers discovered a suspicious hole underneath the grandstands at a historic NASCAR track. Was it a sinkhole? Was there once moonshine in there? I went to see it myself.

Last week, many of you sent me this BREAKING NEWS:

A moonshine cave! I was not aware that this was a type of cave. Nor was I aware that you might find one underneath the frontstretch grandstands at the North Wilkesboro Speedway. Neither were the folks at the speedway. A few weeks ago during tire testing, the operations team noticed a crack near Turn 1. When they drilled down into the concrete to see if the ground had softened beneath, they found… no ground at all. They kept drilling holes. What they discovered was a 700-square foot chasm, the size of a one-bedroom apartment, where there should have been dirt.

That part is very real. The next part is very much … speculation.

If you don’t already know, Wilkes County has a reputation for being a place where people made a lot of moonshine. Hell, that’s why the North Wilkesboro Speedway exists—Moonshine runners who outran the law wanted a place where they could determine who was the best driver with the fastest car. Hence, in 1947, Enoch Staley opened a 5/8 mile dirt oval three miles east of town. The track’s been there ever since. Jack Combs, who later came in as a co-owner, financed his stake with moonshine money.

Over the years, people figured that someone was probably making moonshine out there, but nobody had ever found proof. And then construction workers found a giant hole under the Turn 1 grandstands. The circumstantial evidence feels strong. Of course, there’s another piece of circumstantial evidence here: North Wilkesboro Speedway is hosting the NASCAR All-Star Race next month. How convenient that this story dropped now!

So, is this really a moonshine cave, whatever that is? And if it’s not, then what is it? For answers, I drove out to North Wilkesboro to have a look for myself.

Full disclosure, the folks at Speedway Motorsports did not let me climb inside the hole. But they did show me the relative dimensions of it. It stretched from Row 1 to Row 12, and was fairly wide. Operations workers pulled out about 600 metal seats, and that area’s basically where the dirt had disappeared.

There were other clues. There was some sort of wall beneath the ground that ran parallel to the track. There were some columns as well. “There were things underneath there that you wouldn’t normally see underneath a dirt-filled bank,” said Steve Swift, Speedway Motorsports’s head of operations. Notably, though, there wasn’t a still or any bottles down there. There also didn’t appear to be any way in or out. Sure, the press release mentions that workers found a “rumored moonshine cave” (marketing!), but everybody here’s careful to say that there’s no way to prove it. “Well, there’s that possibility,” Swift said. “When we saw there was a larger cave, it became really plausible that some of these stories may be true.”

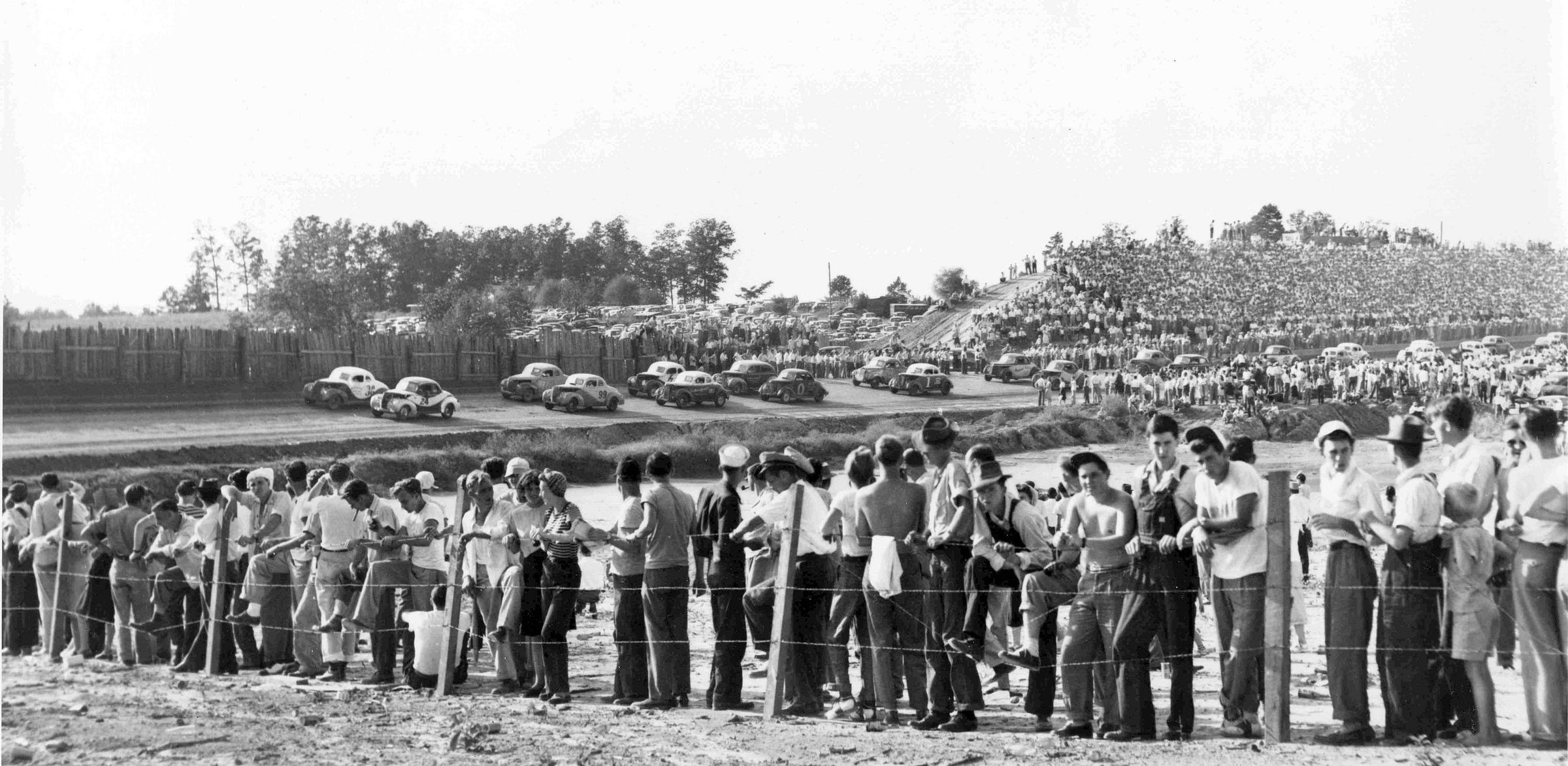

Some quick history here. The speedway opened in 1947, and it was fairly crude in the early years. The 5/8 mile oval was dirt, and it had an uphill and downhill stretch because Enoch Staley apparently ran out of money when he was grading it. There weren’t really any stands per se. Instead, Staley pushed a bunch of dirt up near the track to create a berm for people to stand on. “There was no engineering,” says Steven Wilson of Save The Speedway, a group that pushed for more than a decade to get the track reopened. “There was no inspection whatsoever when they plowed that field up. Over the years, that berm just stayed there. They eventually topped it with concrete. They put seats on half of it. They put bathrooms and concession stands and suites on top.” Until the track reopened, most of the improvements at the speedway were done piecemeal.

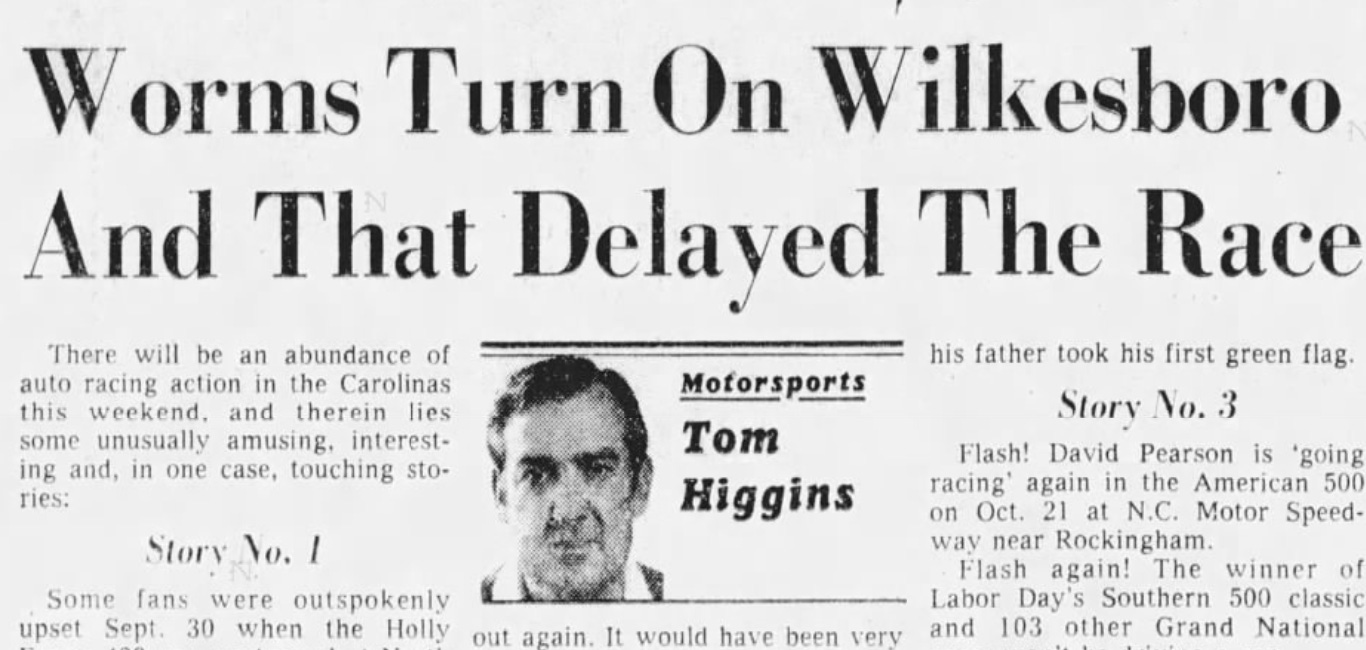

Because of that, there have always been drainage issues at the track, most notably in 1979. That’s when the fall NASCAR race at North Wilkesboro was called off. Because of worms.

Basically, it rained for a week before the race, and millions of earthworms crawled out of the soupy infield muck and sought refuge on the pavement. Workers shoveled up 20 gallons worth of them, and shoved thousands more down into drains. Another round of rains closer to race day sent even more worms out onto the asphalt, and the whole thing was delayed for two weeks until October 14. “I’ve heard of it raining frogs, but never worms until now,” Richard Petty told the Charlotte Observer’s legendary racing reporter Tom Higgins.

The drainage issues continued. Wilson says the track installed a drain pipe that ran underneath Turn 1 sometime in the 1980s. Its purpose: To keep the infield from flooding, which would keep future worm delays from happening. That pipe was clogged or collapsed years later, and the water would pile up and eat away at whatever was in its path. “You could scratch at the retaining wall, and the wall would just fall apart,” Wilson says. Folks tried to unclog the pipe, but after the track was abandoned after 1996, it wasn’t a huge priority. That changed when Speedway Motorsports announced North Wilkesboro’s reopening in 2022. When renovations began, fixing drainage issues was at the top of the list.

That history is why Wilson thinks that time and hydrology are the real culprits behind the cave. “The more sober explanation could be that it’s just a bunch of water that eroded this away,” he says.

Swift noted that yes, water could have come in through cracks in the concrete on top of the berm. Or it could have washed things out from below. But there’s something a little odd about this particular hole. When they were trying to understand how big the void was, workers filled it with water. “Usually you’ll see the outskirts of red clay, which is what we see in the hole, right?” Swift told me. “Normally, if it’s an erosion problem, you’ll find that trailing of red stain where [the water] left.” They didn’t see that. The water didn’t go… anywhere. Swift says the good news was that the water test showed there wasn’t a larger sinkhole underneath the cave. (For what it’s worth, sinkholes aren’t a naturally occurring phenomena in this area. Almost all are caused by erosion or busted drainpipes, like the one in Hickory that swallowed a Corvette.) Then, there were the buried columns and wall. Again, weird. “Where they were placed from an engineering stance, they weren’t to support the grandstand,” he says. “It was kind of bizarre.”

There was one more clue that something was up. While renovations were going on, Paul Call got a little fidgety. Call had worked for the speedway for more than 60 years, and lived in a trailer across from the ticket office. For more than 26 years, he was the track’s only employee, and served as its caretaker. He saw NASCAR return to the track just before his death last November.

Swift says that during the renovation process, his crews were working on the suites that sit above the grandstand, and tried to pull some heavy equipment up on top of the berm. “Paul, as fast as he could move, came up here and stopped us,” Swift says. “He said ‘Do not get over this section. There’s stuff underneath here that you might fall through.’” Call never said what might be down there, exactly. But he knew something was up.

There’s long been liquor at the track, but it was there for drinking, not for distribution. “I know there were jars of moonshine here in the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s,” Swift says, “and I know there was some here last May.” But there’s never been any evidence that it was made or stored here. Wilson has recently talked to a lot of people with deep roots at the track. They all told him that Enoch Staley would never have allowed it. It was a line he wouldn’t cross, and a big risk that he wouldn’t have taken. “It was just an urban legend,” Wilson says of the moonshine cave.

That said, North Wilkesboro wouldn’t have been the first NASCAR track with a moonshine operation running out of it. In 1967, a year after the Middle Georgia Speedway opened, the feds found a moonshine still hidden in a bunker near Turn 3. It was capable of making 80 gallons of liquor a day, and was accessible through a trap door underneath a ticket booth with a tunnel that led 17 feet underground. The still ran during races, mostly because the fumes from the cars masked the fumes from the mash. The track’s owner was arrested, but later found not guilty.

Moonshine was made a few hundred feet from the North Wilkesboro property, though. Dean Combs, a former race car driver and the son of former co-owner Jack Combs, was busted in 2009. Dean, being the nice guy he is, used his tractor to help ALE agents drag his stills up on to a hill near the track, where they blew them up. “Everybody knew it,” Dean told me in 2014, two years before he was busted again. “I was proud of what I was doing.”

And then there’s the topic of illegal liquor itself. People love moonshine stories for one simple reason: They’re awesome. Reporters find them problematic for another simple reason: They’re almost impossible to fact-check. The only time they cross over into tangible reality is when people actually get busted for it. Then there’s hard evidence, police reports, sworn testimony, and so on. People in Wilkes County have insisted to me that there were better drivers and moonshine runners out there than Junior Johnson, the legendary NASCAR Hall of Famer who grew up down the road from the track. But Junior’s famous, they say, because he got caught.

Hence, the moonshine cave story will always live in the chasm between fantasy and reality, which is where legends are born. “I wish we could have found, you know, a case of moonshine,” Swift says. “But sometimes the mystique’s a little bit more interesting than just finding the hard evidence.”

In this case, there wasn’t much time to be sentimental. By the time I got to the track, workers had already pumped six truckloads worth of concrete into the hole to shore it up. After I left, they pumped in even more. “It’d be great if we had the time to do a true archaeological dig,” says Swift. “We don’t have tons of time. We have a race right around the bend. We can’t play archaeologist too long.”

As I watched some local television reporters grabbing footage of the hole and doing standups, I chatted with a man in a yellow construction vest. His name was Will Kulczyk, and he was one of the guys from Sendek Concrete in Boone who’d come down to fill in the chasm and shore up the grandstand. We talked about some of the past races he’d seen here, and all of the work that he had ahead. At one point, he looked at the hole. “Moonshine, huh?” he said. “How could it not be here?”

More North Wilkesboro Stories

(Every time I think I’m out, they pull me back in!)

“Ghosts of North Wilkesboro” - SB Nation, 2015

My Mom remembers her parents buying a house in Charlotte in the 40s, where they found jars of moonshine hidden in the walls. She didn’t know what they did with it (though I imagine my uncles “took care” of the problem)!