There’s a quote that I’ve been using for years to describe the absurdity of bringing racing back to North Wilkesboro. It came from a conversation that I had over lunch with Robert Johnson in 2014, back when he was still mayor of North Wilkesboro. We were discussing what it would take to bring racing back to the speedway. Johnson was an electrician who’d done work at the track to bring a few small races there back in 2010. He thought for a moment. “Well,” he said, “you have to have people that have deep pockets and don’t care a lot if they take a little bit of loss on it, for the love of the sport.”

It didn’t hit me in the moment, because I’d gotten a good chuckle out of something else that was said over lunch. As we waited for our food, the son of the track’s founder had told me about a season ticket holder whose ashes were scattered on the track by Richard Petty before a race. “If you think about it,” Mike Staley said, “all that dust flying up there, all of those people eating hot dogs, everybody got a little piece of that guy.”

But later, driving back home, I kept on thinking hard about what Johnson had said. All you need is a race-loving millionaire who doesn’t care about losing money. That person, I concluded fairly quickly, did not exist on this planet. Or any planet.

Turns out, I was wrong. That person is Marcus Smith.

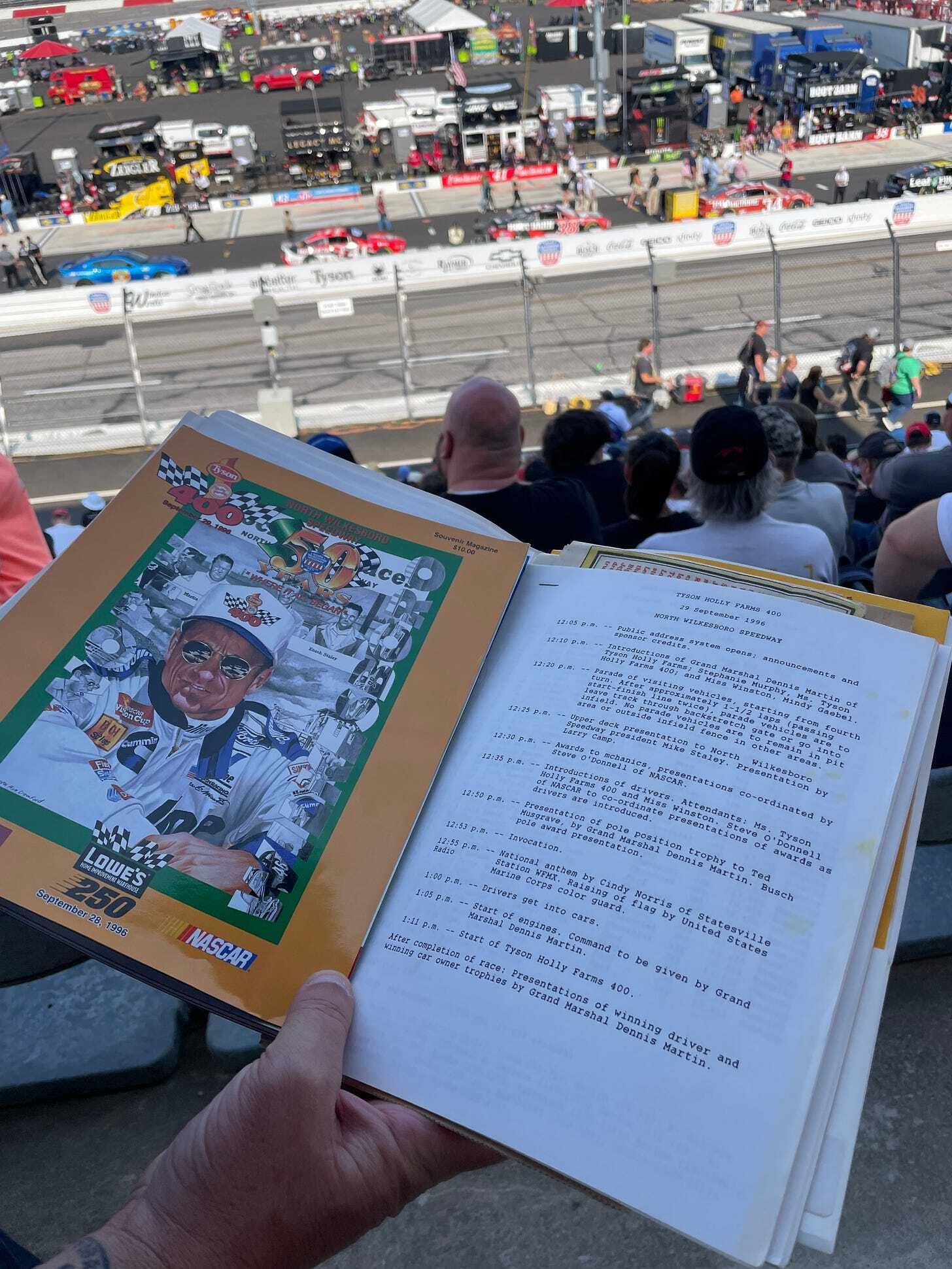

Last night, I listened to him as he talked to reporters in the media center after the NASCAR All-Star Race, which was the first time that Cup Series cars had run a real race at North Wilkesboro since 1996. Marcus speaks softly, with a tone that you’d use to put a baby to sleep. He didn’t say anything that he hadn’t really said in the frenzied weeks leading up to the race. He’d like to keep the pavement in place for as long as he could: The current asphalt on the .625 mile oval was laid down in 1981 (before the race, Richard Petty and Darrell Waltrip remarked that they had raced competitively on that exact same surface). It’s too early yet to say when Cup cars might return, although racing of some sort will definitely be there to stay. Mostly, he was grateful to his staff and the community, which had worked at a breakneck pace to get a track that had been abandoned for quarter-century ready for a bona-fide NASCAR race in less than a year.

Nobody asked Marcus if the All-Star Race lost money. It was clear that he probably could have made more revenue by holding it at any of the other tracks that he owns through his company, Speedway Motorsports. Still, I suppose I could have asked Marcus about the money thing at his press conference, but it wasn’t really the moment for that. He was still basking in the glow and genuine admiration he’d received all day. Remarkable, really, considering that his father, Bruton Smith, was the man most responsible for closing the track down for good and was maybe the most hated man in Wilkes County. His son may be, for the moment, the most loved person in that same place.

I wasn’t sure if I was going to write about that. Or about anything, really. I had a media credential for the race, but I’ve been writing about North Wilkesboro for almost a decade now, and I didn’t really know if there was anything more to say. It didn’t help I spent most of my day at North Wilkesboro Speedway walking around, slack-jawed, unable to really make sense of what I was seeing. I was around for the big late model race last August, the one that Dale Jr. almost won. Back then, everything felt sort of how I remembered it from its fallow years. Everything felt temporary there, from the lights down to the port-a-potties. The track was going to be renovated, sure. But back then, things truly felt like stepping back in time, from the crowds walking in to the traffic clogging roads in every direction.

Sunday felt… different. The place had been glowed up, but not in a way that made you feel that something at its core had changed. Bristol and Martinsville are short tracks too, and they don’t look anything like they used to, really. This felt like a North Wilkesboro that could actually exist in 2023 and into the future, rather than a event designed only to hit folks my age and older squarely in the feels.

Still, I walked around, not really knowing what I was supposed to feel. First, I took a stroll through a midway outside the track dedicated to selling merch, and realized that when I first visited Dean Combs’s house in 2014, there was a clear view from his back porch to the then-rotting racetrack. Today it was impossible to see it, thanks to the sea of RVs, tractor trailers, flags, and people. I walked up to the main gate and noticed that Paul Call was sitting out in front of his mobile home. This man, now in his 80s, mowed the grass and let untold numbers of people into an abandoned track to look around. Now, tens of thousand of people surrounded his house.

I watched the Open race from turn 2 (and discovered that people really do not like Ty Gibbs). I tried to cross into the infield afterward and ended up being sort of herded up next to the stage for the driver introductions. A guy in a lime green Dale Sr. shirt and vintage ‘80s Oakleys told me I needed to smile more.

On the way back to the media center, I ran into Jeff Gluck, the excellent long-time racing reporter who, until that point, I’d only chatted with over Twitter. He asked what it felt like to see this place come back to life after writing about it being dead for so long. I sort of stumbled through an answer. I couldn’t really fathom it. It is impossible to totally wrap your head around an event as big as this, especially in a place as improbable as this.

The All-Star Race itself was, well, not very competitive. Kyle Larson dominated most of it, at some points nearly lapping the entire field, which is sort of a North Wilkesboro thing (By the time ABC cut to what would be the very first live televised NASCAR race, the 1970 Gwyn Staley 400, Richard Petty had already lapped the entire field). Afterward, Larson talked about how he’d like to see a few more places where the asphalt was a little more grippy and a little less worn down, in order to make the racing a little more competitive. Drivers were competing against the track, as opposed to competing against the other drivers, he said. Not that he was complaining. Larson had just won a million dollars for finishing first.

Larson, though, made a simple statement that contained multitudes: “This place feels like a racetrack to me,” he said. The fans felt much closer here. They could have left once it became clear that Larson was running away with the thing. They stayed. They sold out a trucks race on Saturday. Hell, the stands were full for a trucks practice before that.

I walked out of the track and drove home after midnight. It was then, as I was being passed by haulers heading down to Charlotte, that I began to make sense of the day for the first time. North Wilkesboro, old as it is, is a symbol of what people are starting to crave in our modern world. Intimacy. Closeness. Authenticity. Jim Utter, another fantastic motorsports reporter, told me after the race that none of this may have happened without the pandemic. Running races without people expanded NASCAR’s view of where races could be run. Plus, relief funds basically fueled North Wilkesboro’s renovations. But the pandemic also made a lot of us realize that screens can only take us so far. There is a limit to what you can experience without showing up and seeing something happen, at close range, with your own eyes.

Gluck told me he was able to rate the crowd reactions to driver introductions for the first time in a long time, because the crowd actually cared. Usually nobody really gets into them anymore, he said. But here, the folks in the stands were fixedated on it. Ross Chastain got the loudest reaction. Kyle Busch came in second, fueled by boos. Clearly, he anticipated them—he and his team took a synchronized bow once the crowd laid into him.

It was small crowd. But an engaged crowd. The track’s capacity is now 25,000. Charlotte Motor Speedway, the site of this weekend's Coca Cola 600, can hold nearly four times as many people. But, would you rather have 100,000 fans who are sort of paying attention, or 25,000 people who are being held at rapt attention? The days of the mass audience are mostly leaving our society. We’re so fractured now in so many ways. It’s easy to go viral, but harder to get people to keep paying attention. I’m biased, maybe, but maybe one thing that still works is this: Do the thing you care about for the people who love it, and hope that it's enough. Sure, the business side of you might tell you to get as many people in the door as you can, charge them as much as they’ll pay, and give them only what they asked for. But that may not be a recipe to get them to come back.

Getting people to come back here is the next frontier. Clearly racing and other big events are returning: Speedway Motorsports wouldn’t have put this much money into this place for one race. What that will look like is still up in the air. Smith wouldn’t say whether he thinks the Cup series will be back next year, and you clearly can’t say that something has gone wrong here if they don’t. Cup cars weren’t really even supposed to be here this year! But if you believe in a future where things happen in places where people truly care about them, it’s hard not to be optimistic about what will come next, whatever that is.

This morning, I went back and looked at my original notes for my original North Wilkesboro story in 2014. The quote I’d been repeating from Robert Johnson was accurate in its wording. But there was another part of it that I’d forgotten. A part that now makes me realize that I’d failed to put what he said into context for years. Johnson hadn’t been merely talking about someone who was willing to come in and lose money forever. Rather, he thought the only way the track would reopen would be if someone would take a big picture view over a short-term pop of excitement. “It’d be a long-range investment if you had the right kind of people behind it and supporting it,” he said. “Not just racing, but other events as well.

“Long range, you could recoup your investment,” he said. “Just not in my lifetime.” That part was sadly prophetic. Johnson died in March, two months before the All-Star Race at North Wilkesboro.

Somehow, he knew exactly what it would take. A lot of us just couldn’t see it.