In March of 2021, I gave the keynote address at the annual meeting of the Friends of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. If you don’t know, the Friends of the MST is the nonprofit that helps coordinate all of the smaller groups that build, maintain, and spread excitement about the trail across North Carolina. I relied on them heavily for the last season of my podcast, Away Message, which followed two groups of thru-hikers who walked, biked, and paddled 1,175 miles from the Tennessee border to the Outer Banks. When the Friends asked me to speak, I immediately said yes. After all, I produced five-and-a-half hours of audio about the trail. I was happy to talk about it for another hour.

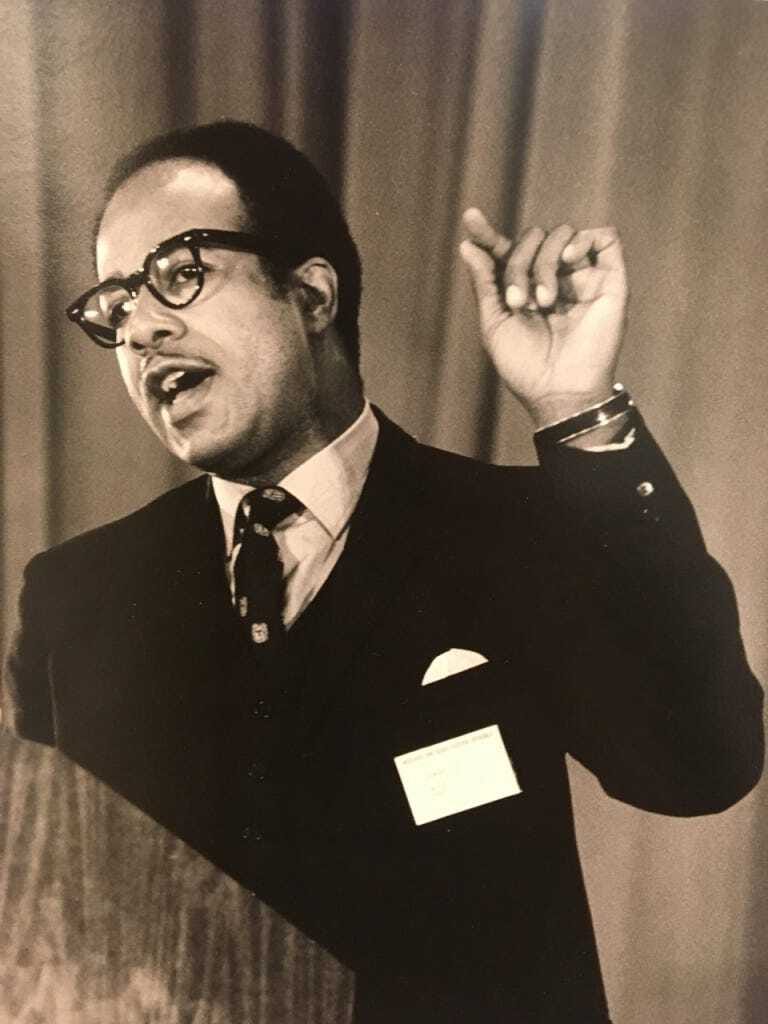

Going back, though, there’s a man from the first episode that I wanted to talk more about: Howard Lee. He’s in his late 80s now, and the racism he encountered early in his life galvanized him to change things in a very specific way. Lee’s long career in public service started when he became the first Black mayor of Chapel Hill. Along the way, he created the MST, sort of by accident. Today, he’s spending his time trying to get more people of color on the trails.

Here’s our fascinating conversation from spring of 2020, which has been edited and condensed for clarity.

“I would never leave the South”

Howard Lee: I've always felt a need to protest against anything I felt was unfair or wrong. My first protest occurred when I was 15 years old, living in a small town in Georgia, southeast of Atlanta. The bathrooms were segregated, and I went to the colored bathroom as it was called that time. It was so nasty that I refused to use it. So I went into the white men's bathroom. But then I really got adventurous, which probably was not smart, and went into the white women's bathroom to check it out. I was beaten up by a group of Klansmen. I got away. And of course, that also taught me a lesson. I made two commitments: The first was that I would never leave the South, because I felt this was my home and that I had every right to be here, but I had to fight for equality and opportunity. The second was never to be so bold as to not figure out the process or plan carefully, and not just try to take the system head on, but find ways to work within the system in order to achieve desired outcomes.

Jeremy Markovich: What drew you to public service?

Howard Lee: Well, growing up in the South, I was always fascinated by public service because my parents were very active voters, or at least attempting to be, but were always denied the right to vote. And so that became a fascination to me as to how America could boast about democracy, and yet deny certain citizens access to the voting booth. So I grew up thinking someday I may have a chance to be a part of this political system.

What really brought it home were two events. I was in the Army, stationed in Texas, and I had been assigned to become a mechanic in the tank motor pool. I just felt that was a misuse of my my skills as a college graduate. So I wrote President Eisenhower, who amazingly enough, sent back a directive through the chain of command directing that I be reassigned to a position more appropriate. And I was assigned to a mental health clinic. That convinced me that there was power in public service, and that if I ever had an opportunity, which I couldn't envision at that time, I was certain to jump in.

The second: In 1966, I took a position at Duke University, and tried to buy a house in Chapel Hill. No realtor would sell my wife and me a house in a predominantly white area. So I went to the local city council, and they refused to pass an ordinance opening up housing. As a result of that, I decided maybe I should run for mayor. And that was the beginning of the journey.

After six months, Lee and his wife were finally able to buy a home in the Colony Woods neighborhood, but people threatened him by phone, and someone burned a cross in his yard. His mayoral race in 1969 got national attention and set all sorts of records in the city: most overall votes, highest number of Black votes, and smallest margin of victory (about 400 votes). The win made Lee the first Black mayor of a majority-white Southern city since Reconstruction.

An accidental standing ovation

Jeremy: Let's skip forward to 1977. What are you doing at that point?

Howard Lee: I was a member of Governor Jim Hunt's cabinet. He'd just been elected governor and he appointed me secretary of the Department of Natural Resources. That was the first time a Southern governor had ever appointed a person of color in any high level position in a gubernatorial cabinet. That department encompassed a number of divisions that were not really divisions in which you'd find a lot of people of color. State parks, state forestry, state fisheries, recreation, environmental management, those kinds of things. And so my responsibility for Governor Hunt was to redesign that department in order to better serve and support local governments in their efforts to carry out their missions related to these specific areas.

Jeremy: So you were in this job, and then the opportunity comes up to speak to a trails conference.

Howard Lee: Yes, I got this invitation to speak to a trails conference at Lake Junaluska (in 1977). The state had started to look more carefully at how to encourage the development of trails around the state of North Carolina. And I, in Chapel Hill, had certainly pushed for that, establishing trails and greenways. So the young person who headed up the [trails] division asked if I would consider proposing that North Carolina should have a trail that ran from the mountains and ended at the sea. And I did.

I think I thought that it would just simply be a throwaway line in the speech. I would say it, people would hear it, maybe it might plant some seed, and everything would go away. Unfortunately, when I cited that line in my speech, the audience rose in unison and gave me a standing ovation for making that proposal.

The problem is that no secretary should be making any major proposals without clearance through the governor's office. I had not cleared that through the governor's office. So as a result of that, I had to come back and explain to Governor Hunt why I had made that proposal, and what I thought the value of it would be. Governor Hunt said that this would be my initiative. I could carry it out, but it would have to be done in a way that didn't involve state funds. So he did approve it. And that's how the Mountains-to-Sea Trail got started. Just from that one line in that speech.

Jeremy: Do you remember what that line was?

Howard Lee: I think basically the line said “It's time for North Carolina to actually commit itself to developing a trail that will stretch across the state of North Carolina, starting at Mount Mitchell and ending at the sand dunes at Manteo, and that this trail someday could become the second most important trail to the Appalachian Trail,” or something along those lines.

Jeremy: And that did it. That got everybody up.

Howard Lee (laughing): Yes.

Jeremy: It sounds to me that whenever you want to do something or achieve something, that it's been meticulously thought out and really well planned. And this is the exception. This is the thing that you kind of just threw out there, and it ended up taking off.

Howard Lee: I'm not sure, if I had thought it through more carefully and analyzed it more thoroughly, that I would have had the nerve to even stand up and make that commitment. Because, frankly, I had very little knowledge about how to develop the trails. Fortunately, the young man who asked me to include that in the speech (Jim Hallsey) was a prolific trails developer and designer within the state of North Carolina and in the department of state parks. He's the one who actually has made this Mountains-to-Sea Trail come to fruition. So within the first year, we were able to assemble approximately 400 acres of land, combining land from the state parks that already existed within the state, from the National Park Service, from the National Forest Service, and from local governments. That would be the original segment of the trail.

After an initial burst, the development of the MST stalled, until Dr. Allen DeHart and other formed the Friends of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. Lee himself would leave state government for a bit before returning as a state senator in 1990.

Howard Lee: I had gone away. I'd actually forgotten about the trail from 1981 until the early 1990s. I had gone back to the Senate and one day as a chance encounter for Dr. DeHart, and he told me what they had been doing and how much progress they'd been making. And I felt a little embarrassed, because I hadn’t kept up with it at all. I'd been busy doing other things. So I became kind of a voice in the Senate advocating again for the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. About ten, maybe twelve years after the speech was made, the trail started to take on a real identity.

Becoming a Hiking Evangelist

After his time in the Senate, Lee became the first Black man to serve as chair of the State Board of Education, and was later the Executive Director of the North Carolina Education Cabinet. He also became a fixture at the annual meetings of the Friends of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, where he always sang a rendition of “Happy Trails.”

Jeremy: Before you proposed the trail, were you a hiker?

Howard Lee: No, no, I had not hiked. I played golf. I played tennis. I did a number of things. But I didn't start hiking until about 15 years ago. I started to feel that I needed to get out and see what I had started and how it was coming along. So I started hiking with different groups of people.

And I'm really committed to keeping this trail going, and I’m certainly enjoying it as much as I can. We have not been able to engage as many minorities into hiking. And so I've spent some time really talking to minority groups, especially young kids, about hiking the trail.

Jeremy: If you really wanted to simplify it, you could say that a Black man created, or got the ball rolling on, the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. Do you think that has any significance in what you're talking about today, in getting minorities out to hike?

Howard Lee: I don't know. I do know that (in 2018) I was asked to come speak at Bennett College in Greensboro. And one of the people there said that she'd heard about the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, and had discovered that it was actually initiated by a Black man. But she didn't know who that Black man was. And she said, because of that, she became fascinated. That's when she discovered that I was the person who actually started this. And so, she became interested in hiking.

It could have some impact. But as I said to her at that time, it's unimportant as to who started it or who initiated it. But I do hope that what we can do is to help minorities become enhanced and intrigued by hiking, by being able to go into the woods and enjoy what, many years ago, was a common thing for the majority of the people.

For more: Listen to Howard Lee and others describe the early days of the trail:

You can also listen to the entire Mountains-to-Sea Trail-themed season of Away Message on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app. All of the episodes are also here, on Our State’s website.