Bojangles has nationwide aspirations. We've heard this story before.

North Carolina's most beloved chicken and biscuit chain has been around since 1977. It's been owned by out-of-towners and private equity firms for a big chunk of its life.

Just like the ACC, Bojangles is expanding to California:

Over the next six years, an entrepreneur named Lorenzo Boucetta plans to open 30 stores in the Los Angeles area. “The delicious chicken, biscuits, and breakfast, combined with strong unit economics and unparalleled support made the decision a no-brainer for me,” he said in a canned statement. This is a far cry from 2015, when the Panthers played in Super Bowl 50 in Santa Clara. Bojangles was a team sponsor, but had to truck in its sweet tea, since its closest location was more than 2,000 miles away. Now, it’s Bo time in the Pacific Time Zone.

Before this, Bojangles had already announced that they planned to open 270 new restaurants, including 20 in Las Vegas, and others in Dallas, Columbus, and Orlando.

About that last city. In 2016, the company closed eight restaurants there, not long after it had announced, you guessed it, ambitious expansion plans. “We love Florida. It's just not going to be anytime soon that we go back to Orlando,” then-CEO Clifton Rutledge said at the time.

Now?

If you feel like you’ve heard this story before, about Bojangles gearing up to take its Southern-inspired food across the country, you’re not dreaming. Over the course of its history, the company has tried to expand to far-flung places, only to contract back to the Southeast, where people know it best. So, what’s behind that? Why does the company try this every couple of years?

Bojangles has had the same name since it opened in Charlotte in 1977, although it did drop the apostrophe in 2020 (It’s not changing the spelling, despite what you may have seen on a new location in Knightdale). But! It’s had at least six different owners over that time, and was a publicly-traded company for a time. So, to have an idea for what could lie ahead, it helps to take a look back at what came before.

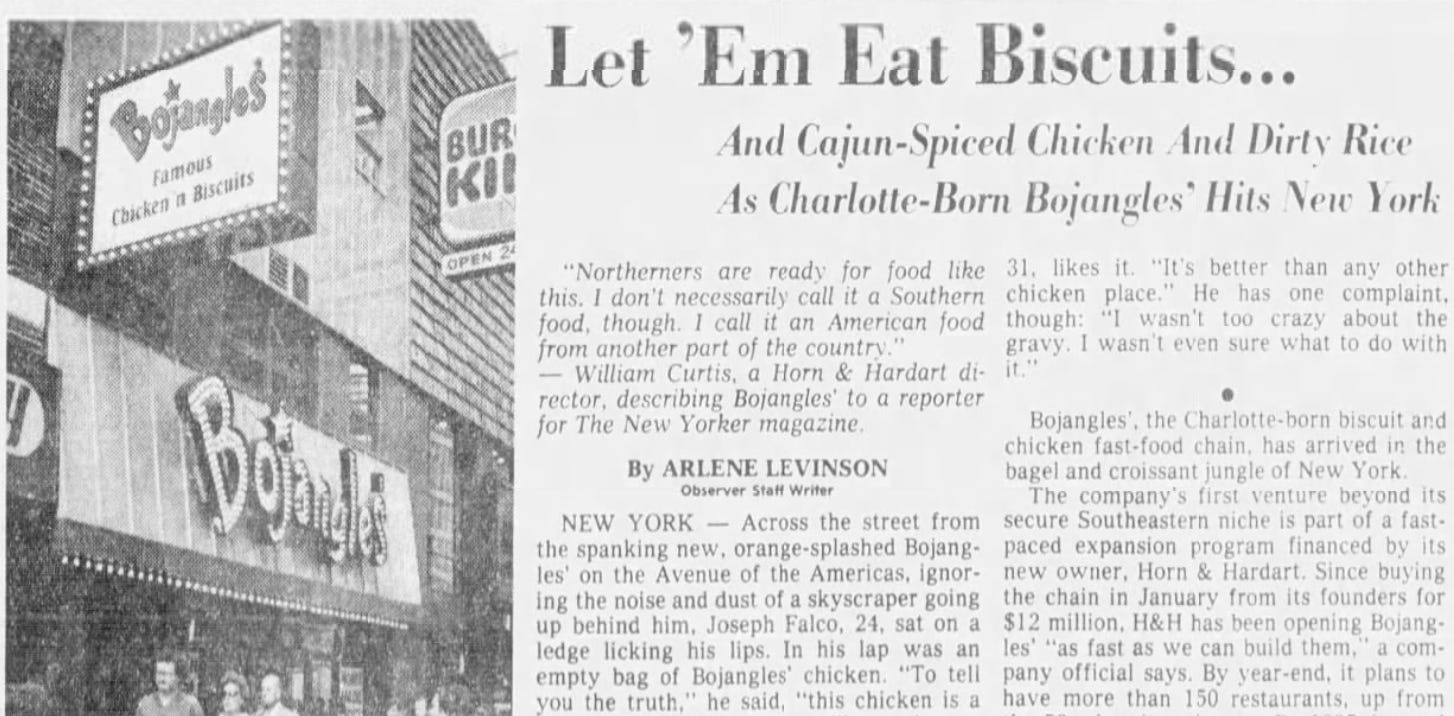

Back in 1982, Bojangles opened a store on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, and this was such an oddity at the time that The New Yorker showed up. A Bojangles executive who lived in New York City was optimistic that people would enjoy a type of food that he’d only recently encountered. “I never saw a biscuit in my life,” said William Levitz, who I’d like to emphasize was in charge of selling New Yorkers on this unfamiliar food. “The big question was would New Yorkers like biscuits. And they do. They love them,” he said. New Yorkers were… okay with the other stuff too. One guy told the Charlotte Observer that he liked the food, although “this chicken is a little spicy.” Others mused about dirty rice. One person wasn’t sure what the gravy was all about. The New York City Bojangles menu didn’t include items that the company thought might confuse the locals. Hence: No corn on the cob, no pinto beans, and no country ham. The last one was deemed “too Southern” by Levitz. Another company executive explained dirty rice this way: “I don’t necessarily call it a Southern food. I call it an American food from another part of the country.”

The New York City store was part of the rapid expansion plan from Horn & Hardart, a fast food company that bought Bojangles earlier in the year from founders Jack Fulk and Richard Thomas for $12 million. In just a few short months, they set off on a break-neck pace of expansion, going from 52 restaurants to nearly 150, and planned to have 600 open by 1986.

Fast forward to 1986. That year, Horn & Hardart announced that it wanted to dump Bojangles completely, calling it a “drain on the company’s earnings.” The company said its New York locations were unprofitable, so it closed them and sold off the real estate. The issues, according to an Observer story in October of that year, were thus:

The company tried to expand into places where it faced stiff competition, and didn’t have enough money left over for advertising.

Anyone who wanted a franchise got one, basically meaning the openings were scattershot instead of intentional.

The company made its food from scratch and ground its own coffee, which was… hard. “To run a Bojangles’, there’s more skill than any other fast-food restaurant you can name,” one franchise owner said.

In Houston, Bojangles ran into KFC, Church’s Chicken, and Popeye’s, which were already really popular. All of the locations there closed. In Florida, white-collar workers, retirees, and tourists didn’t really like the menu that was popular in the Carolinas, so the company tried new items and made its breakfast platter bigger.

The company had 328 locations, then shrunk back down to 152 before Horn & Hardart sold it to Sienna Holdings for $24 million in 1990. The new owners said they’d concentrate on Bojangles locations in the Carolinas.

In effect, the company went from having Las Vegas owners to having Los Angeles owners.

They tried to brighten up the colors (although CEO Dick Campbell said he purposely left the iconic orange in place) and made renovations. Still though, the company didn’t turn a profit until 1996, and the private equity owners had wanted to cash out by then. They decided to sell.

In 1998, new investors bought the company for $85 million and moved the headquarters back to North Carolina. The company decided to grow again, partly because opening new stores would help the new owners pay off their debts, and partly because Popeye’s was expanding into Bojangles’ territory. Then another guy came in in 2001, bought out the CEO and put himself in charge. “The industry had been drained by investors interested in making a quick buck, but the food service industry is not constructed that way,” new CEO Joe Drury later reminisced to Greater Charlotte Biz. He focused on updating the company’s current restaurants. “Our plan was to stop planning new locations and start cleaning up our own backyard.”

Even so, by 2005 the company had expanded into Jamaica, Honduras, and China. In that last nation, Bojangles found that people wouldn’t eat white meat, so they changed to dark. The company also had no American workers in China, which led to cultural misunderstandings, according to the Observer:

That’s meant overcoming the Chinese aversion to throwing away food no longer fresh enough for U.S. standards. Initially, [the company’s general counsel] said, savings-oriented employees turned out restaurant lights during the day—another no-no. Chinese workers also wanted to stay on the job longer than the hours that Bojangles’ allows.

Two years later, the Chinese mall that the Bojangles was in closed, and so did the Bojangles. The Jamaican locations also folded, although there is still at least one Bojangles open on an island in Honduras.

On a positive note, this era provided the greatest crop of Bojangles commercials, mostly featuring Carolina Panthers legends Steve Smith and Jake Delhomme.

You complete me, Steve Smith.

Speaking of the Panthers! In 2007, Panthers owner Jerry Richardson and former Bank of America CEO Hugh McColl took over the company with their private equity investment firm, Falfurrias Capital. “This is a remarkable opportunity with a company that has a good track record,” McColl said at the time. “We don’t have to leave the Carolinas to have growth.”

By 2011, they were ready to sell, because private equity firms often want to make money quickly and get out. In Falfurrias’s case, they only planned to hold on to Bojangles for four to seven years. In its time as owner, Falfurrias shrunk the menu to only its most popular items while it expanded to some 500 stores in the Southeast. It didn’t have the ability nor the desire to go further out. “You won’t see us opening 20 stores in Arizona,” managing partner Marc Oken said at the time. “People never heard of Bojangles’ there.”

In July 2011, yet another private equity firm, Advent International, bought Bojangles (they didn’t name a sale price). That company took Bojangles public in 2016 and, by some estimates, quadrupled its investment. The company’s CEO then, Clifton Rutledge, told me that he thought the company would expand slowly and cautiously, but might someday have 3,500 locations.

It was a public company for all of three years before, you guessed it, a pair of private equity firms bought it and took it private. The company had started to lose money again. “Bojangles’ Sale Leads To Questions About Fixing It” read a headline in the Observer. Experts thought that, once again, expansion outside of its core market—the Carolinas—might have led to problems with profits. Rutledge abruptly resigned. Stores closed. The menu shrunk some more.

Which leads us to today.

Again, if you operate under the premise that private equity firms only want to hold on to their companies for, maybe, five or so years, then it’s gettin’ to be sellin’ time for Bojangles again. Which means it’s time to make a splash. Expand some more! That feels logical.

It’s also helpful to know a few other things, though. One is that private equity firms own a lot of fast food chains, so much so that it’s rare to find a chain that’s not been taken over by one. Cook Out, Chick-fil-A, and In-n-Out Burger are some notable exceptions. It’s also not unheard of for a regional chain to want to stretch its legs beyond its normal territory. In-n-Out Burger, a California staple, is expanding to Tennessee, for example.

There’s also the balance between company-owned locations versus franchises. One mergers-and-acquisitions expert told me that franchises can often be more successful, since local managers have more of a vested interest in each store’s success. When the new owners took over Bojangles in 2018, they said they’d planned to flip 25 to 30 company-owned stores over to franchises instead. Their plans are detailed, as evidenced by a 647-page franchising document that puts the total investment cost of a new Bojangles franchise between $2.2 and $3.6 million, real estate not included (A few more notes here: In 2021 and 2022, Nearly 9-in-10 Bojangles orders were not eaten in the restaurant, more than half of the sales happen during breakfast and lunch, and the average check is $10.22).

All of which is to say, Bojangles is once again seeing if a broader swath of Americans will be interested in an American food from another part of the country. If you believe in Bojanglifest Destiny, though, you’ve already seen the future, spoken to you by the voices of the ancients. See Jake, I told you they would come.

Thank you for the great background/context, Jeremy. My neighborhood Bojangles, which switched to drive-thru only during the pandemic, has remained drive-thru only and is doubling down on that by adding a second drive-thru lane, a la Chick-fil-A, which has mastered the drive thru game.

Regardless, my local Bojangles makes the best damn biscuits in town, and I’ll keep going there as long as they keep up their biscuit mastery.

It feels like they go big or go right back home when they haven’t seemed to try spreading out throughout their region more gradually. I get LA and Vegas and international stores seem great, but more locations in WV, MS, TX(!!!), and some of the other midwest states might be a bit more welcoming. Most of these states have a location as-is, but you have to build on those. It could be a situation where it’s more advantageous to open up in some smaller areas with less competition. Bojangles wants to fight with KFC, Popeyes, Canes, and Church’s, but they keep doing it directly instead of strategically.