NOTE: Portions of this story mention suicide.

“Dear Mary and Margaret,” the letter began, in clean, typewritten prose. “Try not to worry. I have been killed.”

The letter was one of three that Gallatin Roberts typed up. That one was left for his wife and daughter. Sometime afterward, on Feb. 25, 1931, after he had calmly and secretly tidied up his affairs, he walked into the bathroom of his law office, above the Central Bank and Trust, pulled out a .38 revolver, and shot himself.

“My papers are in the box under key,” his letter concluded. “The key is in my pocket. Good bye.”

Roberts was 51. He’d grown up without a father, and spent a lot of time trying to be the honorable man that he wished his dad had been. In 1895, he was getting ready to enroll at Weaverville College, and rode into Asheville to buy a new suit. But he’d left the suit in his wagon, and it was promptly stolen. Roberts didn’t have money to buy a replacement. Soon after, though, police caught the thief, and Roberts spent a week in court testifying. But he also watched the attorneys in awe. After that, he wanted to become a lawyer.

After law school at Wake Forest, Roberts opened his own office in Asheville in 1904, then started holding various political posts. County attorney. State representative. In the General Assembly, he worked on voting rights, in particular the secret ballot and women’s suffrage. He was twice the president of the North Carolina Forestry Association. He was a director of one bank and on the board of another. He was an elder in his Presbyterian church. He was married, with two kids.

He became mayor of Asheville. Twice. During his first term, everything seemed to be going right for his city. Asheville had already become the third largest city in the state, behind Charlotte and Wilmington, a decade before. Between 1880 and 1900, the population had grown more than five-fold. During that period, the railroad arrived, and Biltmore was constructed. Those artisans stayed in town, and put their talents to work constructing any number of new civic buildings. The Art Deco City hall was conceived in the 1920s and finished in 1928. Same with the courthouse. Building permits alone brought in millions during that decade, and stories of Asheville’s decadence were influential to the novels of Thomas Wolfe. Legendary city planner John Nolen had finished a master plan for Asheville during Roberts’s first term, from 1919 to 1923, and would later remark that the town incorporated more of his ideas than any other city. When Roberts came back to office in 1927, that plan was becoming reality. New buildings were popping up all over town.

And then, the Great Depression exposed the thing that had been driving all of that growth: enormous debt. In the long term, that debt and a decision about what to do with it would put Asheville in a situation that no other city in America faced. The pain it inflicted would make the Asheville of today into a place that’s unlike any other in North Carolina. In the short term, though, the revelations led Roberts to resign as mayor. Months later, he was indicted. “I am guilty of no crime. I have done no wrong. My hands are clean,” he typed in a letter. “I shall demand an immediate trial.” The letter wasn’t found until after his death.

Walking through Asheville today feels a bit like walking through the Asheville that Gallatin Roberts knew. If you look at pictures of the city from roughly a century ago, many of them look a lot like they do today, albeit devoid of color and modern cars. The town is dripping in history in a way that many of North Carolina’s cities are not. Part of its allure is its hub spot in the mountains, along with its restaurants and breweries. But part of it is that it feels … historic.

Which is funny, because a lot of southern cities have a longer history. Take Charlotte. Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of times past knows that Charlotte was a hornet’s nest of rebellion during the Revolutionary War. It’s always been bigger than Asheville. More successful than Asheville. Charlotte had a gold rush in the mid-1800s, before California’s. Then the city had a textile boom. After that had waned, along came banks. Today, Charlotte’s skyline rivals the largest American cities, far and away more spectacular than any other in the Carolinas.

Some one hundred years ago, Asheville also experienced a period of skyrocketing growth. But complaining about the lack of historical preservation has long been an easy dunk for people in Charlotte. Asheville, conversely, gets praise for what it saved—it now has the largest collection of Art Deco-style buildings outside of Miami. Why?

Almost every city in America faced an existential crisis during the Great Depression. But Charlotte and every other city found a way to bail itself out after the Great Depression. Asheville did something that no other city did. It spent the next 40 years paying back every single cent it owed.

Asheville’s population was 2,000 when the first rail line reached town in 1880. After that, tourists began to show up. The original Battery Park Hotel opened in 1886. The city installed streetcars. In 1888, the first health sanitarium opened. “We became particularly popular among pulmonary patients, but most especially popular with people with tuberculosis,” says Dr. Kevan Frazier, a historian and guide with the Asheville By Foot tour company. “Before the end of the century, Asheville had garnered a reputation as America's tuberculosis capital. That's not what you want to put on the Chamber of Commerce brochure there.”

Soon, sick visitors were being supplemented by rich ones. “There's a battle between hospitality and medicine,” says Frazier. “And by this point, hospitality has more political clout.” But the tourists coming for the fresh air, the cooler summers, and the beautiful mountain views don’t resemble many of the tourists of today. “Tourism, as we know it is a product of the late 1800s, and the middle class, while burgeoning, is still fairly small,” says Frazier. “Paid vacation is decades into the future. Back then, some folks came to us for two, four, six, even eight weeks. That tells us these are people of means, and that's how we end up with folks like George Vanderbilt.”

In 1889, Vanderbilt started building his Biltmore estate, and after he finished in 1896, the artisans, architects, and construction workers stayed in town and worked on any number of projects. The city kept growing. By 1920, the population had surged to more than 28,000, making it the fourth-largest city in the state (Winston-Salem was the biggest, followed by Charlotte and Wilmington. Raleigh was just behind Asheville in population). By 1930, it had nearly doubled, to 50,000. On top of all that, roughly 200,000 tourists were coming every year as well.

Asheville was hot. What happens in hot towns? People start snapping up real estate. Speculators would grab land, or options on land, and then turn around and sell them quickly for higher price. Brand new neighborhoods appeared all over the place, often segregated by design. The Grove Park Inn had opened in 1913. The Grove Arcade downtown was under construction and would open in 1929. To keep up with the growth, the city of Asheville itself went on a building boom in the 1920s, and constructed its now-iconic city hall and courthouse, four elementary schools, Asheville High School, a tunnel, Pack Memorial Library, the City Market Building, and a new public golf course. There were new, beautifully landscaped parks. “Cities and counties today? They react,” says Frazier. “They widen a road because there's so much traffic on it. In the early 20th century, there's more proactivity. In Asheville, they're making moves for where they saw Asheville going.”

To be proactive, Asheville ran up an enormous amount of debt in the form of municipal bonds. “Those are basically the tool that cities have to use to borrow money,” says Frazier. “They don't go to banks and ask for mortgages and other loans.” Since most cities don’t have enough cash on hand to fund ambitious or expensive projects, they issue bonds, and then pay back those bond holders over time. There were two big differences between the bonds that Asheville and other cities were issuing in the 1920s versus today. First, the cities didn’t have to ask voters to approve the bonds. Second, there was far less regulation.

By 1925, Asheville’s debt was nearly $140 million worth in today’s dollars, which was a lot of money for a small city. “Asheville had thought before the Great Depression that by 1950, its in-town population would have grown to about 500,000,” says Frazier. “Looking at the numbers, that's not an unreasonable thought. They didn’t want to stop the growth. They just didn’t want it to be helter skelter. I don't think they were spending recklessly.”

Even so, there were warning signs of things to come. For one, tax collections had been down since 1922. For another, the real estate market started to cool off in 1926. Home prices in Asheville dropped nearly 50 percent between 1927 and 1933. People were worried about the price tag of all of the city’s improvements, but the city was still riding high. Gallatin Roberts rode that high as he returned to the mayor’s office in 1927. His last term was “clean, honorable, efficient and progressive,” a campaign ad said. He would go into office without “promises or obligation.” His character was “unimpeachable.” But soon after his election, he came upon a secret that would lead to his downfall.

When Roberts took office in 1927, an Asheville Citizen article talked about the issues that he’d face. Among them: Annexation, supplying water to the county, and more. There was also the mention of the big projects that Asheville had undertaken over the previous four years. Roberts said he didn’t plan on taking on any new debt.

Behind the scenes, though, Roberts was discovering just how shaky the situation was. At some point early on in his term, the mayor learned that the city had stashed $3,250,000 in deposits at the Central Bank and Trust in downtown Asheville. In June of 1927, the Asheville Times declared the bank to be one of the strongest and largest financial institutions in the state. But as the real estate market came back to earth, the bank became vulnerable. A later study found that Central Bank was overloaded with bad real estate loans which would later become worthless.

Roberts had, at one time, been a member of the board of Central Bank. As mayor, he was faced with a no-win situation. If he protected the city’s money by pulling it out of the bank, then the bank would fail, which would cause other banks to collapse and cripple the local economy. If he left the money in, the bank might collapse anyway and the money might vanish in a bank run. After the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929, the impact wasn’t immediately felt in Asheville. But rather than tell the public what he knew about the bank, Roberts kept it a secret. If people found out, they might panic, start a run, kill the bank, wreck the economy, and the money would be gone.

To try and keep things afloat, Roberts came up with a plan: He and the city would actually take out more bonds to prop up Central Bank. The bonds were to pay for new city improvements, but Roberts and others never actually made the improvements, because paying for them would pull money out of the bank. The plan was meant to buy time, but according a recounting in the Mountain XPress, Roberts became increasingly desperate:

A bank assistant cashier, Charles J. Hawkins, who was tasked with bringing promissory notes to Roberts, characterized the mayor as a nervous wreck of a man by 1930. In court testimony, Hawkins described the erratic behavior Roberts exhibited when he asked for the mayor’s signature: The mayor would instruct Hawkins to close the door to the office, and Roberts would pace back and forth, sometimes for minutes, before signing. Occasionally, Roberts would ask why the notes were being issued and inquire about the financial condition of the bank. Hawkins would then leave City Hall as inconspicuously as possible.

In public, Roberts and other tried to be cheerful and reassuring, even as the Great Depression started to take hold. But then, in November 1930, a bank collapsed in Tennessee, which started a chain reaction that led to the collapse of Central Bank. As a result, several other banks in Asheville failed as well. “We lost every penny we had,” Beulah Hoffman told the New York Times decades later. Her teacher’s salary had been $3,000 a year. It was cut to $720, and the city couldn’t pay it. Another woman and her husband lost their new home. “We had to move to the country so we could make a garden,” Joyce T. Leonard told the Times. “My husband's father loaned us a milk cow. There was merely enough clothes to wear and food to eat. That was all we could hope for.”

Soon after, an audit revealed what Roberts and others had done. The next month, Roberts resigned, and in a letter to the public, laid out what he had tried to do to save the bank and the city’s deposits. “I could have wrecked that bank any day in the last two or three years,” he wrote, while stating that he was constantly reassured that the bank was solvent. “Any person can look back now and say what they would or would not have done. But if they had the responsibility, would they have closed the bank’s doors in the face of thousands of hard working men and women?”

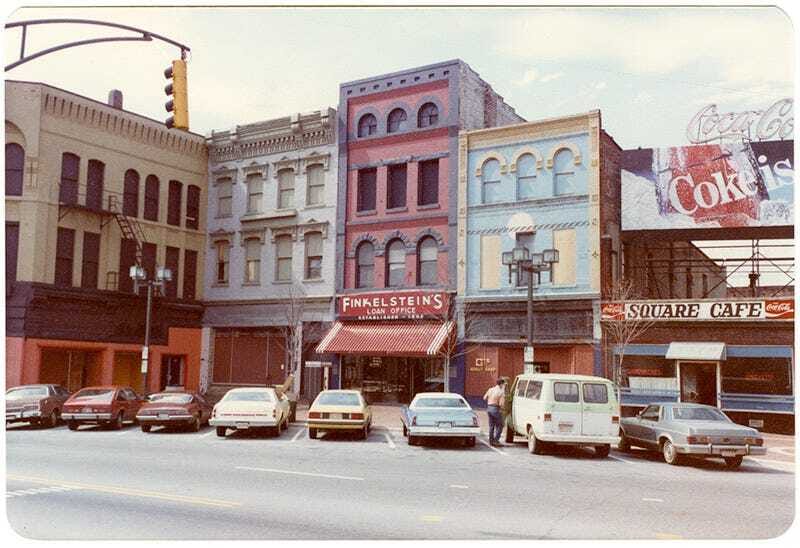

The letter didn’t stop Roberts and other public officials from being indicted alongside bank leaders in February 1931 for misuse of public funds, despite an audit that showed that he and others didn’t personally benefit from their actions. Two bankers committed suicide. Days after the indictment, Roberts shot himself near his law office, a few floors above the Central Bank and Trust. In addition to the notes he left for his family and an associate, he wrote one last letter to the public: "My soul is sensitive, and it has been wounded unto death. I have given my life for my city, and I am innocent. I did what I thought was right."

The city was shocked. Some 10,000 people came out for his memorial service. Immediately, public opinion about what he’d done shifted from anger to sympathy. Still, though, the city had to figure out what to do about the missing money and its crushing debt. In 1932, it tried to challenge the validity of the bonds by claiming that it was misled by a previous auditor. But the federal judge who got the case didn’t agree. Creditors sued to get their money. It wasn’t until 1935 when the judge made a decisive ruling. “I have ransacked [legal libraries] in an effort to find some high authority [that] would enable me to relieve the City of Asheville of its liability,” Judge E. Yates Webb said in a quote from the Asheville Citizen. “I must confess to you that I have been unable to find it. On the contrary, I have been thoroughly convinced … that there is no legal way by which Asheville may be relieved of her obligations.” His rationale: The city would continue to benefit from the construction and improvements that it paid for with the bonds. Because of that, it needed to pay that money back.

That decision changed Asheville, and the city decided to consolidate its debt with that of Buncombe County and several other districts. Crucially, city leaders locked in lower interest rates—at the then-rates of 6 to 7 percent, the city could have been paying back its debt forever. On July 1, 1936, Asheville agreed to pay back everything that it owed over the next 40 years, some $48 million in all (Roughly a billion dollars in today’s money). That decision made the city the only one in America that didn’t default on its Depression-era bonds. It also crippled Asheville.

The city budget was cut in half, firefighters and police officers faced layoffs, and the entire street maintenance crew was let go. City employees who were left had their paychecks cut by at least 20 percent, and some were paid in scrip. Some of the brand new buildings had to be abandoned, because nobody would lease them and it cost to much for upkeep. The state took oversight of many of the city and county’s services. And the entire city government was changed to the more transparent council-manager structure that remains in place today.

Thomas Wolfe used this period as the basis for the town of Libya Hill, a fictionalized version of Asheville that he described in You Can’t Go Home Again:

They had squandered fabulous sums in meaningless streets and bridges. They had torn down ancient buildings and erected new ones large enough to take care of a city of half a million people. They had leveled hills and bored through mountains, making magnificent tunnels paved with double roadways and glittering with shining tiles — tunnels which leaped out on the other side into Arcadian wilderness. They had flung away the earnings of a lifetime, and mortgaged those of a generation to come. They had ruined their city, and in doing so had ruined themselves, their children, and their children’s children.

In some years, debt payments were nearly half of the entirety of Asheville’s budget. The inability to pay for new things made it hard for Asheville to grow. “There are a few years in the middle of 20th century when Asheville actually recedes in population because they have no money to invest in infrastructure,” says Frazier. “The first line on the city's budget, for decades, was the debt service. And on top of it, the state of North Carolina would not let them annex because of this enormous debt. Cities would typically grow their tax base is through annexation. That the state does not allow Asheville to do that until somewhere around the late ‘70s or early ‘80s.”

After World War II, many southern cities underwent a dramatic change. “The rest of the Sun Belt, from Florida to southern California, starts growing by leaps and bounds for a number of reasons,” says Frazier. “One: The land is the south was very underdeveloped in comparison to the northeast. There's a lot of it, and it’s low cost. Two: Warmer weather draws people. When air conditioning gets introduced, then you can go even further south. I mean, Florida was never gonna have a giant population before air conditioning. Then we see industry, and that's when we start seeing the rise of cities like Atlanta and Charlotte.”

Asheville? It was crumbling. “The city government held on for dear life,” Roger McGuire, a local booster, would later write, “making those bond payments, and frantically patching everything — patching streets, patching sidewalks, patching sewer and water lines, and providing a patchwork of services.” Because big businesses often couldn’t get the city services they needed, many of them skipped over Asheville. “There are businesses that can’t be on septic, they have to have sewers. They can’t be on wells, they need municipal water supplies to do their work,” Frazier says. “And so, they looked elsewhere.”

There was another effect. The desire for urban renewal that began in the 1950s led cities with more money to demolish old buildings and build new ones. Asheville was still broke, and largely didn’t have the money to do so on its own, although federal funds led to urban renewal programs that largely targeted and displaced nearly half of the city’s Black residents (The project that replaced existing houses with public housing in the East Riverside neighborhood was the largest urban renewal project in the southeast). There was some redevelopment downtown to make way for I-240 and the Civic Center, but many other buildings remained vacant.1 “There's not this movement of new business into Asheville, so there's not this pressure to tear things down,” says Frazier. The low rents, cheap real estate, and old buildings started to attract young, politically liberal people from elsewhere. “Despite the large overall loss of population and the dead downtown, they came to Asheville for its low cost of living, a growing arts and crafts community and artsy old buildings,” wrote Sasha Vrtunski, now an affordable housing officer for the city of Asheville, in an academic paper about the city’s downtown revitalization. “Many of these folks would become active in civic life through the preservation group that was started in Asheville in 1976.”

On July 1st of that year, 40 years to the day of its first payment, the city finally paid off the last of its Depression-era debt. In a ceremony at the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium, city leaders burned the last actual paper bond. It didn’t light on the first try.

After a videotaped message from Rev. Billy Graham, Asheville’s mayor led the crowd in a cheer: I’m glad I’m an American and I’m glad to be in Asheville. “Certainly this is a trademark of the greatness that the mountain folks have always had,” he told the crowd.

When he was growing up in Asheville, Frazier remembers his mother driving him through downtown when he was eight years old. “We were stopped at a stop light on Pack Square,” he says. “I was looking over at one of the stores and I'm like, ‘Mom, why do adults need their own bookstores?’” There were porno theaters and pawn shops downtown. Other buildings were abandoned.

That long period of economic depression ended up setting the stage for the Asheville of today. “Historic preservation is building steam in Asheville in the mid-seventies at about the same time that that debt service gets paid off,” Frazier says. “The community tenor was: Let the misfortune of the Great Depression be our fortune. We were too broke to tear anything down. So let's not start doing it now.” The people attracted to low-cost Asheville were the ones who kept the city from making some bigger missteps in the early 1980s, when suburbs were ascendant and malls were in demand. Around that time city leaders, now free of their crushing Depression-era debt, came up with an idea. They’d sell new bonds to finance a plan to tear down old buildings, clear out nearly 11 blocks of downtown, and build a new mall in the center of Asheville. But unlike in the 1920s, the city couldn’t just sell bonds on its own. It had to get approval from voters. So city leaders put a new bond issue on the ballot in 1981.

Asheville said no. Fiscal conservatives and historic preservationists joined forces to vote the bonds down by a 2-1 margin.

After that, the city decided to go back to the drawing board, and over the next two decades, the city and its people made slow but impressive progress on bringing downtown back to life. “These buildings are surely part of the reason Asheville was able to revitalize,” Vrtunski wrote. The downtown mall’s defeat was another. But it took a lot of people working together to bring things back. It also took an odd stroke of luck: The city emerged from its dark period right at the time when preservation was in vogue. “If the debt had gotten paid off in the early fifties,” says Frazier, “I think we'd be a very different looking city than we are today.”

Today, Asheville’s unemployment is among the lowest in the state, and its property values are higher than almost anywhere else in North Carolina. New construction is popping up all over the place. It’s a boomtown once again, and the debt that once had a hold on daily life here is mostly forgotten. “I don’t think we see the lingering effects of that now,” Frazier says. “I mean, we’re close to 50 years past the final payment.” Despite everything that’s happened over the last hundred years, some of the same things still bring people to Asheville. The mountains. The cooler temperatures. The lively, walkable downtown. Good transportation (The railroads have been replaced with Interstates 26 and 40, and there are now cheap direct flights to Florida that make it easy for folks there to escape to their second homes). Still, Asheville’s relatively small size and its old buildings may be here to stay. “That may not change any time soon,” says Frazier. “It may just be the remnants of that part of our history.”

In 2013, an old trunk showed up at the North Carolina Room at the Pack Library. Inside were old pictures, letters, diaries, and scrapbooks that belonged to Gallatin Roberts, donated by his granddaughter. A librarian, Betsy Murray, began to categorize, digitize, and transcribe everything inside. There was a picture of the crowd gathered outside of the Central Bank, shortly after his death. Another picture shows thousands of people outside of his funeral. There were tax returns and journal entries. They paint a picture of his thoughts and moods during the bank failure and his resignation. And, there was the typed note to his family to say goodbye.

Murray was most drawn to Roberts’s handwritten autobiography, which contained the previously unknown story about his absent father, the stolen suit, and the testimony that pointed him toward career in public service, a career that would lead to the end of his life and decades of pain for Asheville. “I was so immersed in it that I felt like I really knew him,” Murray told the Mountain XPress in 2019. At some point during the interview, she started to tear up. “I knew I was going to cry,” she said. “I get real emotional about this.”

(The research for this story is based on historical articles from the Asheville Citizen-Times, the Buncombe County Special Collections at the Pack Memorial Library, and the work of the Mountain XPress, in particular Coogan Brennan and Thomas Calder. Special thanks to Sasha Vrtunski, Blake Esselstyn, and Kevan Frazier for their help, time, and guidance.)