NOTE: This story was originally published in September 2023.

Tuesday was Election Day in Sanford, a town with a population of 30,000. Only 24 people showed up in person to vote.

The result wasn’t particularly close in the only race on the ballot. Byron Moses Buckels won the Democratic city council primary in ward 4 with 88% of the vote (Congrats?). Also, almost all of the ballots cast were cast early. In all, only 185 voters participated in a race with 2,872 eligible voters. That’s a 6% turnout. Pretty bad!

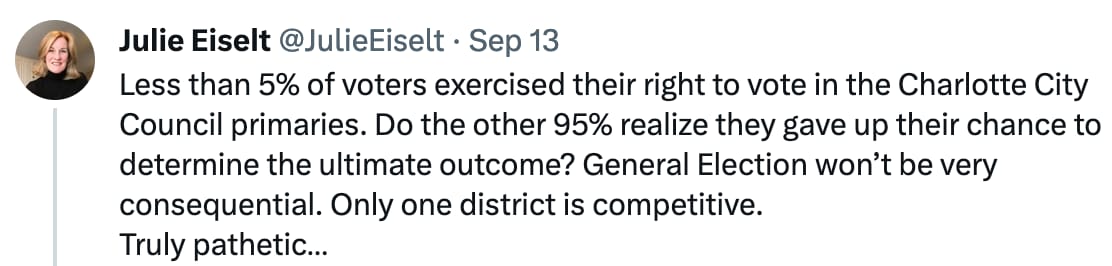

Could be worse. Charlotte held a primary election on Tuesday as well. Turnout was just under 5%. Sure, there’s also a general election coming in November, but since the city leans heavily Democratic, this is the election that’s the most consequential. Sure, there was no Republican primary. Sure, the mayor’s race wasn’t competitive. Still, in a city of almost 900,000 people, its most important local offices were chosen by only 24,000 voters. Everybody seems kind of pissed off about that!

WFAE’s Steve Harrison pointed out that Charlotte’s turnout was dead last among America’s 50 largest cities, and also that it’s one of the few big cities with partisan elections. Charlotte political mucketymucks told Harrison that Charlotte ought to think about changing the way it conducts elections.

Maybe don’t hate the players. Or the game. Hate the calendar.

Federal elections are held in even-numbered years. So are state elections. In North Carolina, there are more than 500 cities and towns, and all but a couple-dozen of them hold their elections in odd-numbered years, like 2023. Almost all of them will have very low turnout.

That’s ironic, since local elections are usually more directly consequential to voters than the state and national elections. Local officials are in charge of schools, city services, zoning, and more. But state and national races get more attention and more money. It’s easier to pay attention to one governor’s race than it is to cover dozens of local races in big and small towns in places that are, increasingly, losing reporters and local news outlets. The attention leads to higher turnout. If you’re already gone to the trouble to get a ballot to vote for president, it’s not that much harder to keep going down the ballot to cast a vote for mayor.

This seems like an obvious problem. But! How exactly did we get to this place? Why do almost all of North Carolina’s cities and towns ask people to vote when a president, congressperson, governor, or attorney general isn’t on the ballot? And if it’s leading to abysmal turnout, why isn’t there a larger push to fix it?

The Purity Theory of Non-Partisan Elections

Back in the early days of North Carolina, elections were a bit of a free-for-all. A town becomes a town through an act of the General Assembly, which grants the town the ability to create a charter. That charter laid out how local elections would be run. It says whether they’d be partisan or non-partisan, whether primaries would be held, and whether there would be a threshold for a runoff. It also stipulated whether elections would be held in even- or odd-numbered years. Hence, for most of North Carolina’s history, its local electoral calendar was a hot mess. Sure, state offices were elected in even-numbered years, which coincided with federal elections. But the rest of the elections usually happened whenever local folks damn well felt like it.

That changed in 1971.

That year, North Carolina’s lawmakers passed a law moving all non-partisan municipal elections to odd years, beginning in 1973 (The handful of cities that had partisan local elections got to keep them in even years). There are no clues in the law itself as to why they did what they did. A few years ago, UNC School of Government professor Robert Joyce made an educated guess. He thought that since most municipal elections were non-partisan, separating them from partisan elections made them more pure. “Maybe, it was thought, there is not a Republican or Democratic way to pave a street or organize a recreation department,” he wrote.

This purity theory has some legs. Maresa Strano from New America’s Political Reform program noted that a lot of states followed along when Congress synced up its elections with the presidential schedule and moved them to even years in 1872. But a sizable chunk of cities and towns didn’t follow suit:

The reason that so many local elections are off-cycle is that, during the Progressive Era of the late 1800s and early 1900s, a lot of municipalities wanted to decouple their politics from corrupt, partisan federal and state politics and party bosses. However, some more problematic reasons were to discourage voter turnout from the people they didn’t want voting, which is a challenge we’re still dealing with today.

Turnout was on the mind of elections leaders in North Carolina in the 1970s, but they stated that odd-year elections would actually get more people to the polls. Alex Brock, the executive secretary of the State Board of Elections, complained to the Durham Sun in 1971 that most city council and mayoral elections were decided by less than a third of registered voters. He hoped the new law would mean local elections wouldn’t be an afterthought during state and national election season. “We will be able to give more coordination to local, state, and national elections,” he said. “I hope this will mean we can assist in raising the level of participation substantially.”

Election structures were a big deal in 1971. That summer, the 26th Amendment was ratified, lowering the national voting age from 21 to 18. After that, North Carolina passed a bunch of reforms to voting. One big change was to put all elections under the purview of the state board of elections to cut down on potential fraud or abuse. It also moved all general elections to November. “It will greatly enhance the image of all municipal elections,” S. Leigh Wilson, the executive director of the League of Municipalities, said just after North Carolina’s election reforms passed.

A Statewide Push For Oddness That Fell Short

This idea, that higher-level elections were a distraction from local or regional issues, persisted through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1985, the General Assembly passed a bill to put a constitutional amendment before North Carolina’s voters. That amendment would have moved state- and county-level elections to odd-numbered years.

“In North Carolina, we have policies, goals and so forth that are not necessarily dependent upon or in concert with … those agendas set on the national level,” the bill’s sponsor, state senator William Martin (D-Guilford) told the Raleigh News & Observer in 1985. He also jumped on the turnout train, and predicted that moving state elections would get more voters to the polls during non-presidential elections.

Republican lawmakers, who were in the minority at the time, called the move politically motivated, saying that North Carolina’s Democrats didn’t want to run on the same ticket as Democratic candidates for president. In 1984, Democrats in North Carolina underwent some severe losses in the same election that sent Ronald Reagan back to the White House for a second term. Republican James Martin rode that wave to become only the second GOP governor of North Carolina to be elected in the 20th century. Republicans made gains in Congress and the state legislature as well. The proper method for rebuilding a political party, said Republican state senator Laurence Cobb in 1985, “is to go ahead and work to get better candidates that you’re not ashamed to be on the ticket with.”

The bill to put the amendment on the ballot in May 1986 passed without much debate at the end of the 1985 legislative session. Political analysts worried that it would decrease turnout and create fatigued voters who would be constantly blasted with political messages every year (How cute). Plus, they thought it would pull focus away from municipal elections, or lead city councils or mayors to align themselves with more partisan forces.

In any event, there wasn’t an organized campaign to push for the amendment, and it went down in flames. About 70% voted no.

Still, the idea of partisan politics encroaching on local races continued to be seen as a thing to be feared. In 2001, a News & Observer editorial criticized a mayoral candidate, Bill Bell, for bringing in big-name national and regional Democrats during his “ostensibly non-partisan” race for mayor of Durham. “Local voters don’t always appreciate big-name bluster from harsh partisans who are briefly alighting in a municipal campaign to launch their stingers and then move on,” the board wrote. “If this episode becomes known as ‘Bell’s Backfire,’ the candidate will only have himself to blame.”

It didn’t backfire. Bell beat the incumbent Nick Tennyson by just 485 votes, and served as mayor of Durham for the next 16 years.

Want More Turnout? Move Your Election To An Even Year! It Works!

Anyhow, this all seems sort of quaint. Today, everything feels partisan and increasingly, all politics feel nationalized (See: national political action committees spending money on local school board races). And, as is quite obvious, predictions about increased focus and higher turnout in off-year elections haven’t come to pass.

Hence, odd-year elections are no longer in vogue. A 2021 study published in the American Political Science Review took a look at what happened when local elections were aligned with federal Election Days. “We find that moving to on-cycle elections in California leads to an electorate that is considerably more representative in terms of race, age, and partisanship—especially when these local elections coincide with a presidential election,” the authors stated. “Our results suggest that on-cycle elections can improve local democracy.”

They later stated: “Every published study on election timing and turnout shows that using concurrent elections is the single most important change that local governments can undertake to increase turnout.” There hasn’t been enough empirical research to figure out whether moving local elections to even-numbered years creates “a more representative electorate.” But in general, the study notes, it’s easier to vote once every two years than once a year. When it’s harder to vote, the electorate skews older, richer, and Whiter. When it’s easier, a poorer, younger, and more diverse voter base tends to come out.

This all feels sort of obvious at this point. But there is evidence that turnout shoots way up when cities move their elections to even-numbered years. Over the last decade, more than 40 cities in North Carolina got individual permission from the General Assembly to change their elections to match up with the federal schedule. The Grand Poobah of state government minutiae, former legislative special counsel Gerry Cohen, notes that when Asheville, Raleigh and Winston-Salem moved their elections away from off-years, turnout nearly tripled.

If you want a piece of trivia that really encapsulates this, here you go: This week in Charlotte, roughly 24,000 people turned out for their Democratic mayoral primary. In 2020, 38,000 people voted in Winston-Salem’s Democratic mayoral primary, which was held on the same day as the presidential primary.

Charlotte’s population is three times larger than Winston-Salem’s.

Hence, says Cohen, changing election days isn’t enough. You have to change the year. “Tinkering with which date in the odd-numbered year to have a municipal election is simply moving the deck chairs on the voter turnout Titanic,” he tweeted this week.

Will it happen? Who knows! In 2016, state lawmakers passed a law that stated: “It is the intent of the General Assembly to provide for even‑numbered year municipal elections, effective with the 2020 election cycle.” They directed a committee to study ways to make it happen and to report back by early 2017. Later that year, a bipartisan group of house and senate lawmakers introduced bills to change all mayoral and city council elections in the state to even-numbered years. And then … those bills immediately died in committee, and nobody’s filed a similar bill since then.

Even so, on a town-by-town basis, more places are moving away from odd-year elections (although some people are still banging the anti-partisanship drum). As recently as June, small towns in Polk, Henderson, Rutherford, Craven, and Iredell Counties got the go-ahead to move their elections to even-numbered years, and more and more are getting permission to make their municipal elections partisan. In an era where sweeping elections changes (Redistricting! Voter ID!) might affect turnout, more and more towns are taking it upon themselves to get more people involved.

So Charlotte and Sanford, it’s understandable that you may be mad about the low turnout. Just remember: There’s always next year.