In February of 1989, just a few months into her job at the tiny Washington Daily News, Betty Gray got a phone call, asking her to look into the city water supply. I’ll do it when I can, she said. A week later, she got another one. I’ll do it next week, she replied. Then another. I’ll do it today, she said.

Those phone calls and a curious editor led Gray, who’d just returned to reporting after a 12-year stint at an insurance office, to look into the story. Gray’s editor, Bill Coughlin, noticed small text on his water bill that said test results were available by request. So, the paper requested them. They showed the water was contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals. At the time, North Carolina law said small towns only had to test for chemicals, but didn’t have to remove them. “The city never denied that those chemicals were there,” Gray told me for a story I wrote for Our State in 2015. “They denied that the chemical being there was a problem.”

In all, Gray and her colleagues wrote 30 stories about the issue, starting in September 1989. The water, they found, had been contaminated for eight years. “We were not real popular with the Chamber of Commerce while this was going on,” she said later. City leaders and others pressured the paper’s owner to ease up on the coverage, or stop completely, saying the attention was hurting, not helping. “It was kind of tough covering the city because the relationship was kind of strained,” Gray’s co-reporter, Mike Voss, told the Washington Daily News in 2015. “But conversely, we’d be going down the street and people would stop us and thank us for doing what we did.”

The city said it couldn’t do anything about it, short of building a new water treatment plant. At one point, the city manager went on TV, drank a glass of Washington city water, and declared that there was nothing wrong. A day after that, the state stepped in and shut the entire city water system down. People in town were ordered to only use the water for laundry. Marines and the National Guard arrived with tankers full of water to drink. State law eventually changed, requiring all cities to provide clean water, regardless of size. Washington found a clean water supply. State leaders said the stories saved lives.

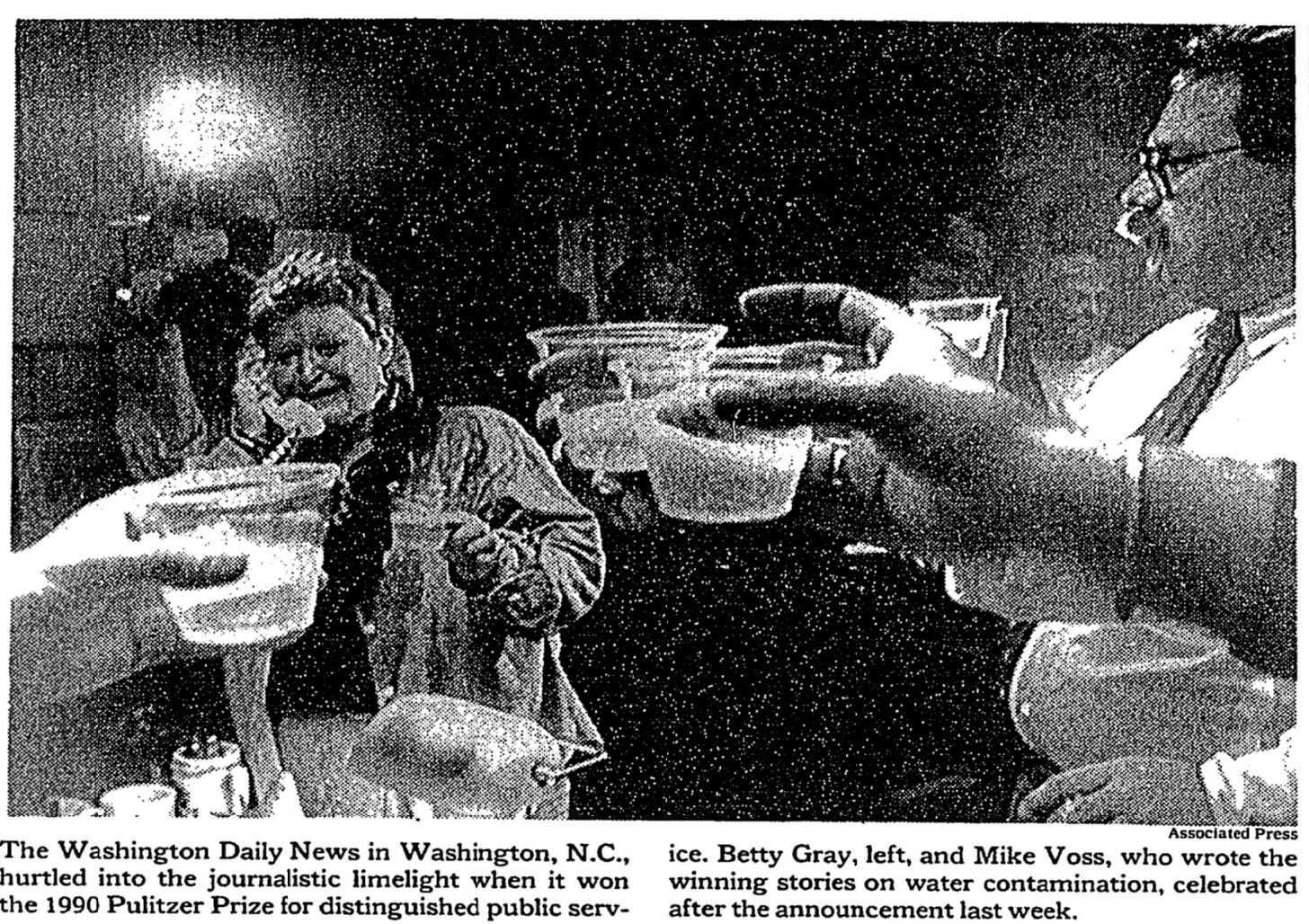

And in 1990, Gray and her colleagues won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. The award did not endear the paper to the town’s elected officials, however. From the Washington Daily News:

The Pulitzer award, however, didn’t smooth things over with the city, likely because the series was published during the lead up to Washington’s municipal election. The mayor and two city councilmen lost their seats that November — had more than two non-incumbent candidates run for office, the other three would have lost theirs, as well, according to Futrell. One city council member wrote to the Pulitzer committee asking them to rescind the award and the three councilmen who remained after the election voted not to recognize the newspaper for its Pulitzer.

At the time, the Washington Daily News, circulation 10,000, was the smallest paper to win it the prize (At least one smaller paper has won it since then). Gray’s father, a voracious reader of magazines and newspapers, didn’t quite grasp the situation. “I don’t think my dad knew how big it was until my picture appeared in the New York Times,” she said.

After accolades, celebrations and a trip to New York City, Gray found herself back in Washington a week later, covering a city council committee meeting. “That really brings you back to earth,” she said. Gray became an editor, then covered the North Carolina legislature for a few years before getting out of journalism to run the public relations team at Beaufort Community College. Her husband was a pharmacist in Washington, and they didn’t want to move. Besides, she could still write. “I’m doing what I was born to do,” Gray told me.

Gray retired in May 2015 after 12 years at BCC. She told me she knows how she’ll be remembered. “I have lived the first line of my obituary,” she said of winning the Pulitzer. “When I die that’ll be the first line. That’s kind of an odd feeling.” Even so, she said the effects of the reporting are bigger than the prize. “I hope our water’s clean,” she said. “I hope that’s our legacy.”