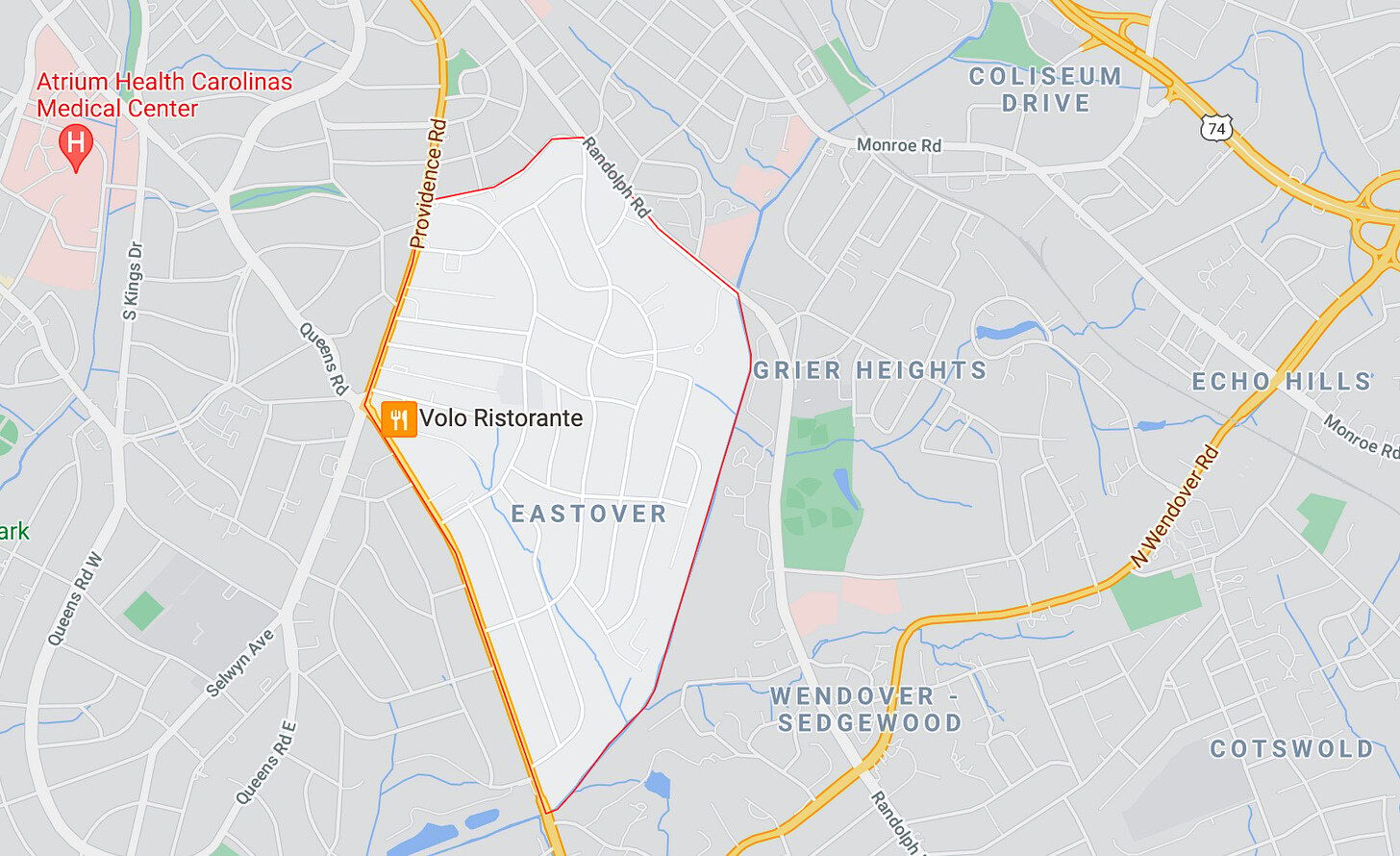

During my first year in Charlotte, in 2005, I lived in an apartment complex called Eastover Ridge, just off of Randolph Road. Every night, I would drive out of the back gate to go to work the overnight shift at a TV station. At the stop light, I sat in my Chevy Cavalier, and always marveled about how the other cars on my side were all BMWs and Toyotas, clean, and in good shape. The cars coming down Sam Drenan Road, on the other side, were beaters, often rusty, with a dragging muffler or a burnt-out headlight. I was new to town, and wondered why that was.

I soon found out: The neighborhood on the other side of the road was Grier Heights, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Charlotte. When that neighborhood showed up on television, it was often in b-roll of flashing blue lights. Later, police would open a new precinct nearby, and installed microphones on light poles to listen for gunshots.

The neighborhood on the other side of Randolph Road was Eastover, one of the richest neighborhoods in Charlotte. That’s where the CEOs and bank presidents lived. The lawns were huge and a deep, lush green. The people on the street were joggers and women pushing strollers down sidewalks. We never, it seemed, had any news to cover in Eastover.

Years later, in 2013, I asked Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police if I could go on a ride-along through both neighborhoods. I was curious about how Eastover and Grier Heights could be so close, and yet so far apart. One side seemed to be impoverished and crime-ridden, while the other felt pristine and safe. Maybe I could get a better sense of the divide.

The officer who picked me up was a nice, young white guy. I hopped into his front seat, and we swung through Eastover quickly. The officer didn’t know much about that neighborhood, simply because police didn’t get many calls from there. Next, we spent more than an hour in Grier Heights as the officer pointed out problem spots, guys who had just gotten out of prison, and apartment complexes where call after call came in, usually to settle a dispute. A large crowd that had gathered in front of a barbershop was gone the next time our cruiser ambled past, not even five minutes later. I asked the officer about this, and he said that people tended to quietly scatter after the police drove by. Over in Eastover, when the rare call did come in, the caller would sometimes ask the cruiser to park in the street a few houses away, as not to draw attention.

The ride-along never actually led to anything. I went back to my notes, which were almost all about Grier Heights, and I decided I couldn’t compare and contrast policing in two neighborhoods when it felt like all the policing was happening on only one side of the street. The only interesting anecdote about Eastover, the bit about where police should park, wasn’t enough to hang a story on, I thought. It seemed too subtle.

The subtlety, though, is the thing I’ve been thinking about this week. I had something else planned for today’s newsletter, but the conviction of Derek Chauvin has been weighing on my mind. Chauvin, a former police officer in Minneapolis, was found guilty Tuesday of murdering George Floyd. That murder last May led to an entire year of upheaval and protest. Chauvin’s conviction alone may not represent the justice that so many people seek, but it could be, as so many have said, a step toward accountability.

It’s easy to focus on big stories like this, because, simply, there’s a narrative. Police, at first, downplayed the incident. Then video emerged of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes. The unrest and outrage led prosecutors to do something they almost never do: charge an officer with murder. The trial proceeded. There was anxiety as the jury deliberated. And then came a large, cathartic release when Chauvin was found guilty, put into handcuffs, and led away. The story had a beginning, middle and an end. It followed a three act structure. There was a climax. And then, a satisfying resolution. A lesson learned.

Real life, however, rarely lines up like this, with overt heroes and villains, with good and evil so clearly split into camps. Things, in reality, are more like long, rambling conversations, where resolutions to agreed-upon problems can be tabled with an effective “yeah, but.” Big moments can make a difference. They can lead to change. But oppression and racism seldom come in clearly-labeled packages. They lie in the subtlety that some can see and some can’t. The things that are wrong are often legal. The inequality lies in the norms.

Over the last few years, I think we’ve all become more aware of the subtlety of our prejudices. To look back at what we’ve done with clearer eyes. I realize that I’m a flawed narrator here. For a while now, I’ve grappled with how I treated stories about crime early in my career in local news. I was far too trusting of police narratives. Short items with mugshots were easy to write in newscasts but, in the aggregate, perpetuated fears and stereotypes about how much crime there was, and who committed them, and how important those incidents were, and what was driving them. Those items were always somewhat compelling, because even when they were short, they were still stories. They had a protagonist, a problem, and, sometimes, a solution. They could be turned around quickly. The information was supplied from a faucet that I could turn on whenever I needed to fill up a newscast. Police are always willing to talk about a bad guy doing who did something bad and got caught. Any criticism, of either the news or the police, came with an initial, knee-jerk reaction. We were, we’d say, just doing our jobs.

I’d been taught early on that it was bad to use the word “allegedly” in news copy. That’s because it places blame on someone without saying who’s accusing them of something wrong. But I’d always almost replace “allegedly” in crime stories with “police say.” And then, just last week, this tweet turned me on my head:

Imagine, if you will, a world in which “claim” was the norm for news stories. A one word change could keep a single source’s narrative from sounding like an official or an omniscient one.

It seems like every day, my beliefs are being challenged, and the older I get, the more I realize that grappling with things I thought I knew is a good thing. If anything, the fact that we’re now becoming more aware of our skewed norms gives me a little hope. I just wish that, years ago, I’d recognized just what it meant that people in one neighborhood could ask police not to park in their driveway, while the people across the road could not.