At 8:45 a.m. on the morning of October 15, 1954, a 28-year-old reporter named Julian Scheer called his editors at the Charlotte News to tell them what he was seeing. Scheer was in Carolina Beach to cover Hurricane Hazel, which had not yet made landfall. He told his editors that half of the people in town had been evacuated. The power was out. The winds were whipping around at 60 to 65 mile per hour. The flooding was widespread. A few cottages and a pier had already been washed away.

After Scheer hung up, he and 33-year-old photographer Hugh Morton headed back out into the storm. They huddled behind a brick structure and watched as a three story building collapsed from the wind and storm surge, which was made worse by the high tide. The town manager, police chief, and Red Cross manager were on their way out of town. The Marines were coming down from Camp Lejeune to help.

Scheer and Morton headed north, and came upon one of the last families still left in Carolina Beach. By this time, it was 10:45 a.m., less than an hour after Hazel had come ashore near Calabash. The family was running in and out of their new ranch house on the sound, a quarter mile from the beach. Water was already covering a low red fence that was supposed to protect the flower beds, and lapped at the pole holding up a basketball hoop. The parents and their two teenage boys were pulling out clothes and loading up their car which was parked on some high ground across the street. Scheer watched as the boys shivered in the wind. One slipped and fell, and dropped a blouse. It floated away.

The parents were worried, but optimistic. “We’re just getting the good clothes,” the mother said as a few volunteers showed up to help. “We’ll let the others get wet. I can always toss them in the washer.”

“Hurry,” the father said, “or we won’t be able to drive out of here.”

The water got deeper, and the wind picked up. The family made one last scan of the house.

“The bike!” one of the boys said.

“Leave it on the porch, son,” the dad replied. “It’ll just get wet. Hurry!” The dad grabbed one last item and moved it to higher ground, away from the rising flood waters. Then he turned off the light switch. “When the power comes back on we won’t have all the lights burning until we get back here,” he said.

Just before the father left, he smelled a strong odor in the living room. “Looks like the gas line broke,” he said. The dad slammed the front door, jumped in the car with the rest of his family, got the water out of his shoes, and drove north, toward Wilmington.

Not even 15 minutes later, there was a flash, and the house was engulfed in flames. An hour later it was gone.

Scheer wrote about the whole scene in vivid detail, and his story appeared on the front page of the Charlotte News three days later. “The next day they came back,” he wrote at the end of the story. “A family of four, looking at a house that was only a black chimney.”

The story wasn’t the thing people remembered, though. It was the picture that ran alongside it on the front page, taken by Morton. In it, Scheer wades through the water as debris and a mattress float by. The wind whips the trees in the background. Flames leap from the house itself.

You can clearly see something in Scheer’s hand. “He’s carrying something,” says Virginia Scheer, Julian’s granddaughter. “Maybe he ran into the house? There’s some kind of story there.” Alas, she doesn’t know what the story actually is, and refers me to her dad.

“There’s a lot of speculation on what he was carrying,” says George Scheer, Julian’s son. He doesn’t know for sure either, though. The picture was taken five years before he was born.

Even though we don’t know exactly what Scheer was carrying, we do know why he was walking in front of the house: Morton said he put him up to it:

Hazel was a very stormy thing. And when it came ashore at Carolina Beach, Julian Scheer and I were covering it for The Charlotte News. I asked Julian to walk through my picture, and the photo won first prize for spot news in the Southern Press Photographer of the Year competition.

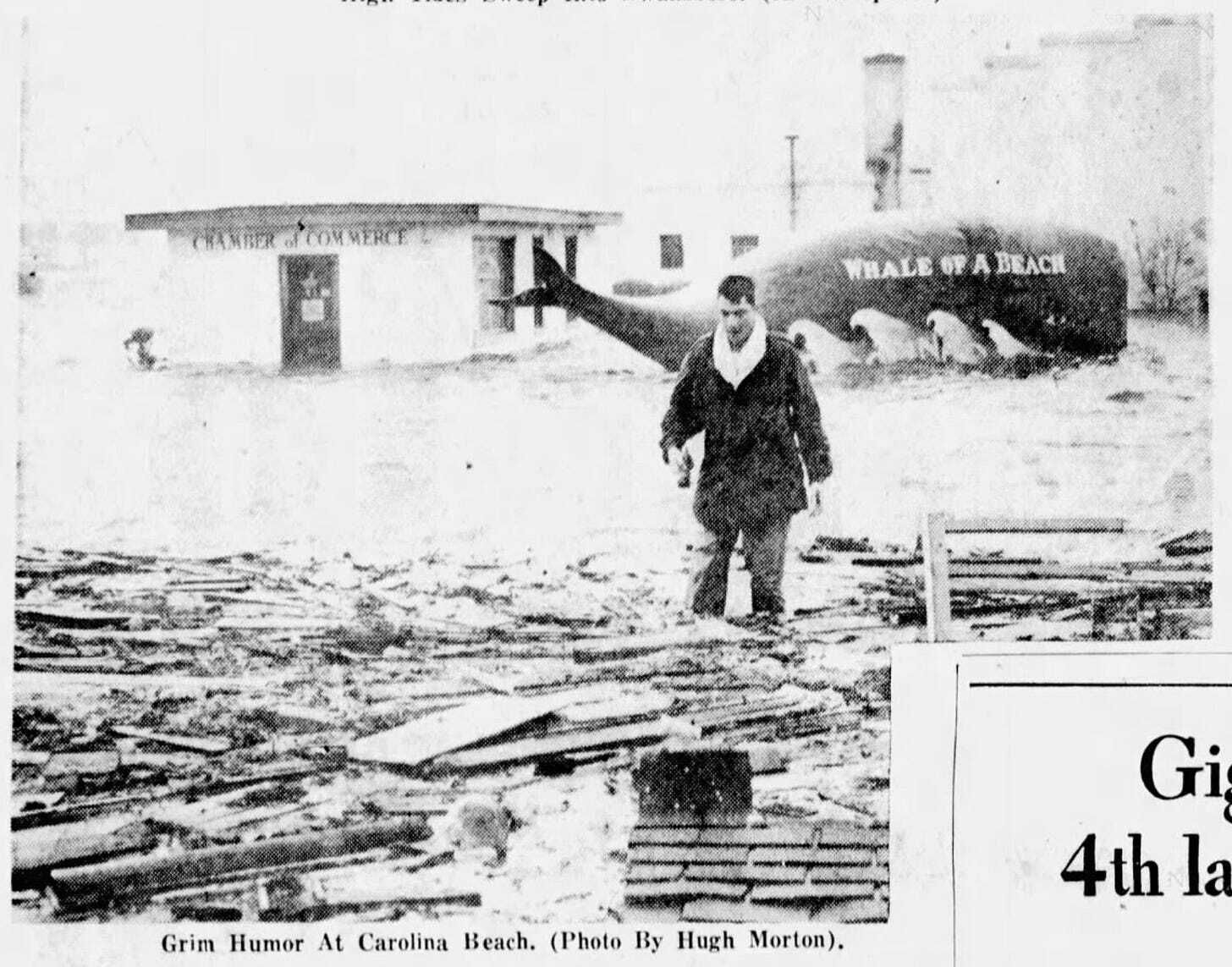

The award was one of many honors for Morton, the longtime owner of Grandfather Mountain whose prolific photos chronicled North Carolina for decades (and were later given to the University of North Carolina). But Morton, who lived in Wilmington, wasn’t the only photographer who took pictures in Carolina Beach during the storm. Life magazine’s Hank Walker was also there, and even got an image of the same house on fire, albeit slightly later than Morton. And this isn’t even the only one of Morton’s storm pictures with Scheer in it. Another photo from the Charlotte News shows him wading through the water near the town’s chamber of commerce, with a large parade float of a whale behind him. “Whale of a Beach,” it reads.

But the photo of the house on fire is one of the defining images of Hurricane Hazel, a Category 4 storm that killed dozens of people even as far north as Toronto and was described by my friend and writer Mike Graff as “the hurricane that changes the way the country thinks of hurricanes.” Morton’s timing, framing, and staging are immaculate. The image has had incredible staying power in the seven decades since it was taken. And while some of the details—the exact location of the house and the identity of the family who lived there—may have been lost to time, the man in the picture, wading his way through chaos, has a remarkable story of his own.

It turns out that Julian Scheer is the reason why hundreds of millions of people around the world were able to watch man take his first steps on the moon, live on television.

Julian Scheer was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1926. At age 17, he joined the Merchant Marines and served during World War II. Afterward, he enrolled at the University of North Carolina, and graduated in 1950. He spent the next few years working as an assistant to UNC’s sports information director. It’s likely that Scheer met Morton during that time, as Morton frequently took pictures of Tar Heel games in Chapel Hill. They definitely got to know each other after Scheer took a sportswriting job with the Charlotte News in 1953. Scheer soon became a reporter and columnist, and covered Morton’s fight to keep a road from crossing the top of his Grandfather Mountain property in August 1954, two months before Hazel. When Scheer later co-wrote a book about legendary UNC running back Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice, he relied extensively on Morton’s photos. He would later talk about hanging out around Morton’s campfires on Grandfather Mountain. The men became friends.

Scheer, however, wouldn’t stick around Charlotte forever. In 1956, a friend who worked for WBTV convinced Scheer to head to Cape Canaveral to watch the Air Force launch some rockets. Scheer was fascinated, but his editor didn’t think it was worth writing about. So Scheer made the trip on his own dime and wrote about them anyway.

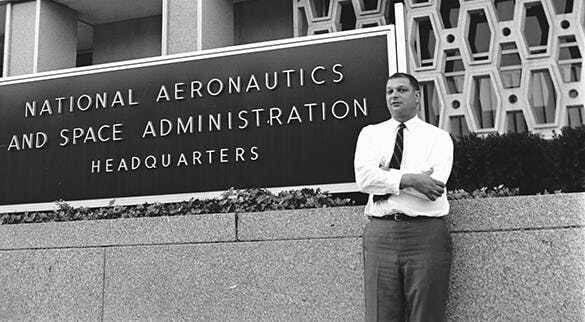

He continued writing extensively about the brand new space program. His reporting and his 1959 book, “First Into Outer Space,” caught the attention of the higher ups at a brand new federal agency: NASA. James Webb, the agency’s administrator, called Scheer up and convinced him to move to Washington, DC. In 1962, he took a job as a NASA public affairs consultant, just a few months after John F. Kennedy declared that “we choose to go to the moon” in a speech. “It’s about marketing the moon,” says Julian’s son George. “That’s what my dad was hired to do.”

Scheer quickly moved up the ranks at NASA, stressing the importance of transparency and authenticity, especially after a fire killed all three Apollo 1 astronauts on the launch pad in 1967. From then on, Scheer made sure that the news media had everything it needed to cover NASA’s missions to send astronauts to the moon. And he had a big hand in the mission that put Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface: Apollo 11. Scheer was the one who suggested the command module be named “Columbia.” The module’s pilot, Michael Collins, liked the name, and it stuck. Scheer helped come up with the wording of the plaque on the lunar lander that says “We came in peace for all mankind” (and famously ignored a request from President Nixon to insert a mention of God). He also was part of the discussions over whether astronauts would put an American flag on the moon, and, most importantly, insisted that the landing be carried live on television. Engineers though a TV camera would weigh too much. Scheer, who had become a powerful force in NASA, overruled them. From an essay published in 2016:

Embedded within NASA’s formative charter was a congressional mandate to report—freely and openly—the program’s activities and accomplishments to the world, unlike the secretive, closed military program in the Soviet Union at the time. “I insisted,” said Julian Scheer, the head of NASA Public Affairs during Apollo. He would not accept any dissent, either from the engineers or some of the astronauts. “They could never see the big picture. But they weren’t landing on the moon without that camera on board. I was going to make sure of that. One thing I kept emphasizing was, ‘We’re not the Soviets. Let’s do this thing the American way.’”

“Without television, Apollo would have been just a mark in a history book,” says Gene Cernan, the last man to walk on the moon during Apollo 17, when reflecting on the importance of television on board Apollo. “The thing that meant so much and brought so much prestige to this country is that every launch, every landing on the moon, and every walk on the moon was given freely to the world in real time. We didn’t doctor up the movie, didn’t edit anything out; what we said, was said.”

Scheer and his public affairs team were largely ex-journalists and writers, but they insisted that anything that came from astronauts be in their own words. Hence, he did not script Neil Armstrong’s most famous declaration: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” In an interview decades later, Armstrong said that Scheer “was absolutely adamant that Headquarters never put words in the mouths of their people, not just astronauts, but anybody, that they let people speak for themselves. They made it known sort of what the party line was and what the NASA position was, but beyond that, they never, to my knowledge, controlled the … public statements of others.”

After NASA finished its last mission to the moon in 1972, Scheer left the agency. He came back to North Carolina to work as the campaign manager for U.S. Senator Terry Sanford, who was running for president. Afterward, he became a communications consultant in Washington. In 1976, he joined LTV Corp. as a vice president, and became its public face through antitrust actions and bankruptcy. He left the company in 1992 and returned to consulting. During his career, he also wrote children’s books, fought for environmental causes, and was instrumental in keeping Disney from building an American history-themed park in Northern Virginia.

Through it all, Scheer remained a friend to Hugh Morton, and often invited him to photograph NASA’s rocket launches. Morton, in turn, honored Scheer with his own overlook at Grandfather Mountain.

Scheer lived in Virginia until he died in 2001 after a tractor accident.

The man responsible for bringing the moon landing live to the world may also have accidentally lent credence to conspiracy theories that the whole thing was faked. Scheer was a founding member of the Man Will Never Fly Memorial Society, a group that was founded in 1959 and dryly insists that planes aren’t real. The society met yearly in Kitty Hawk to make tongue-in-cheek declarations like: “Man will never fly, and if he does he won't come from Dayton.”

During a meeting in December 1969, the New York Times showed up and later wrote a story entitled: “A Moon Landing? What Moon Landing?” The reporter noted Scheer’s role that year:

Mr. Scheer narrated films showing what appeared to be the moon's cratered crust outside a spacecraft window and astronauts walking on a bleak moonlike surface, loping about in one-sixth gravity and floating in raw space. Other pictures showed an array of scientific instruments among boulders and small craters. Actually, the movies were of simulations at space agency training facilities. The scientific instruments were set up not on the Sea of Tranquillity but in a rock quarry in Michigan.

“The purpose of the film,” Mr. Scheer said, “is to indicate that you can really fake things on the ground-almost to the point of deception. You can come to your own decision about whether or not man actually did walk on the moon.”

The whole thing was a joke, but theories that the moon landing was faked have been hard to dispel. The conspiracies even inspired a movie last year entitled “Fly Me To The Moon,” in which the lunar landing was mocked up in a television studio in the event that the mission wasn’t successful. The person in charge of the whole project is played by Scarlett Johannson, whose character was loosely based on Scheer. “Scarlett Johannson, she was my granddad,” says Virginia Scheer.

In the end, Scheer helped create one of the most important images in world history, and before that, in North Carolina history. The shot of a young Julian during Hurricane Hazel is hung up in his son George’s study in Lenoir. His granddaughter Virginia has one too. It’s personal to her. “Everyone in the family has a framed copy,” she says. "It’s kind of one of those classic family photos.”