NOTE: For this edition of the Rabbit Hole, I’m turning over the newsletter to David Fleming, a Charlotte-based writer for ESPN who just published a book about the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. I’ve been kidding for years about the inability of anyone to actually find the MecDec, a document that predates the 1776 Declaration of Independence that we all grew up learning about. David’s book changed my mind. He does a great (and entertaining) job of laying out why the MecDec is actually our nation’s true founding document, why Thomas Jefferson sucks, and why we don’t hear about it more often (even though the date of the MecDec’s signing is on the state flag!). So for you MecDec believers who may have been irritated with me around May 20th every year: My bad.

As part of my penance, I’m sharing an excerpt of David’s book. It’s not about the 600-mile ride made by Capt. James Jack to take the MecDec from Charlotte to Philadelphia in 1775, but the bicentennial re-creation of that ride 200 years later. It includes a backflip, some Philadelphia-style boos, and a well-timed arrest. Hope you enjoy. -

H. A. “Humpy” Wheeler was the longtime and beloved former president of the Charlotte Motor Speedway and a man who single-handedly pushed NASCAR to its peak popularity in the early 2000s with his own unique approach to PR. (A method that was, shall we say, equal parts pro wrestling, patriotism, and Ringling Brothers.) When I first moved to Charlotte, I did a lot of local sports radio, which meant endless “arguments” on air with cohosts like Humpy about my outrageous NASCAR takes on issues like, you know, increasing driver safety and banning the Confederate flag. Once, during a commercial break, the silver-haired and self-deprecating Humpy confessed to me in his classic Carolina drawl that he had actually inherited his nickname from his dad, who got caught smoking Camel cigarettes when he was a kid. I have no earthly idea if that’s true or if Humpy made that up on the spot. What I can confirm is that Humpy is impossible not to like. He was 40-2 as a Golden Gloves boxer as a kid, and in the late 1950s he played defensive line for the University of South Carolina Gamecocks before carving out a Hall of Fame career in PR in Charlotte.

To this day people still talk about Humpy’s insane pre-race publicity stunts. Like the time one Memorial Day weekend when he staged a full-scale military reenactment of the invasion of Grenada on the infield at Charlotte Motor Speedway, complete with a squadron of Apache helicopters. It was so authentic, in fact, Humpy had to call the local sheriff and convince him we weren’t experiencing a Red Dawn–style incursion.

But even Grenada couldn’t top Humpy’s greatest PR stunt of all time: Jerry Linker.

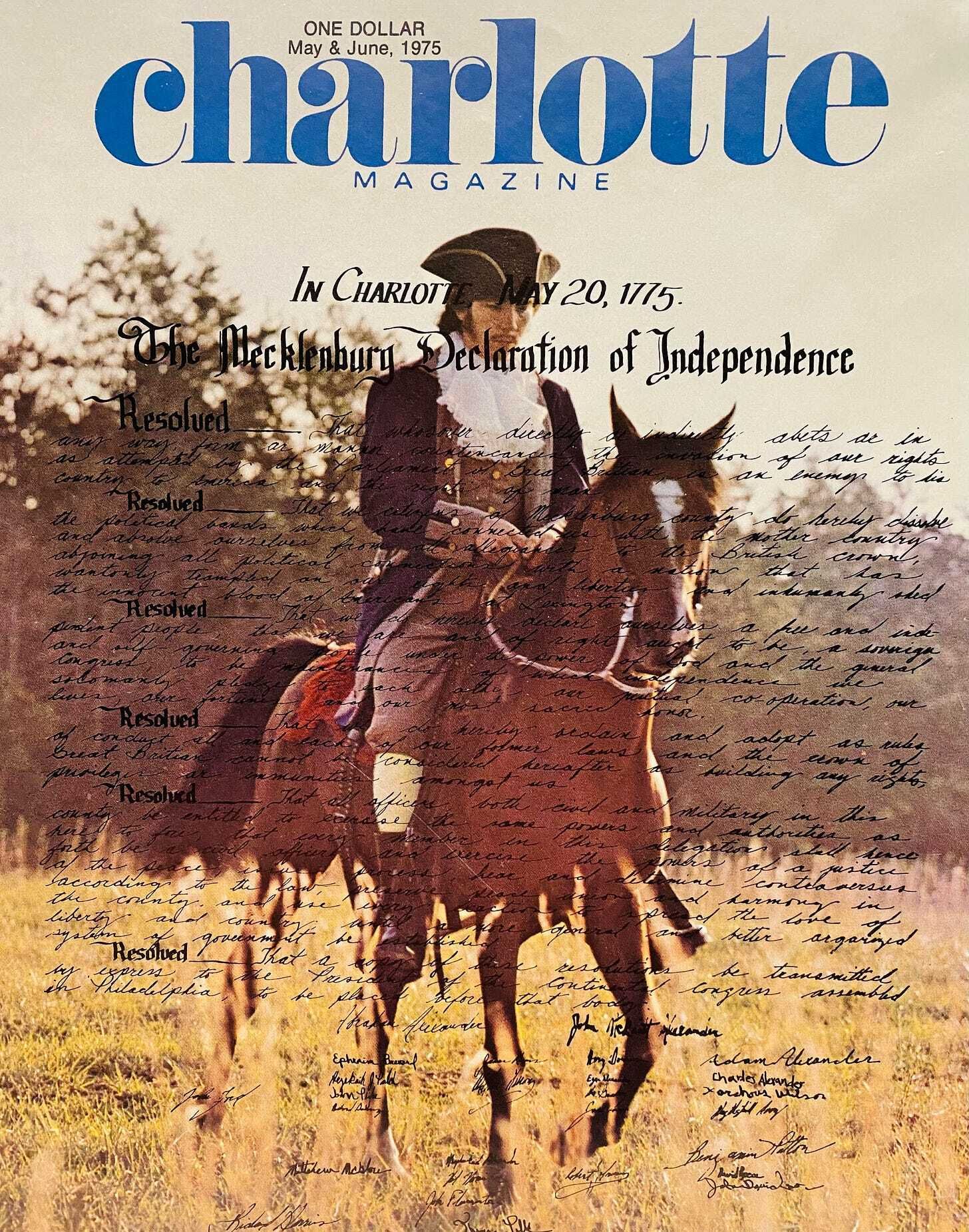

In May 1975, as vice chairman of the committee in charge of Charlotte’s bicentennial celebration of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, Humpy, then thirty-six, came up with the brilliant (and slightly deranged) idea of promoting the event by having a local equestrian dressed in authentic Revolutionary garb recreate Captain Jack’s entire six-hundred-mile ride to Philadelphia, where he would then deliver the MecDec, for a second time, on its bicentennial anniversary. This was Humpy the PR Hall of Famer at his absolute best, bringing one of America’s original true patriots back to life in spectacular fashion for a country chomping at the bit to start its own bicentennial celebration in 1776.

So, it turns out, there was no need for me to jump in my MINI and re-trace Captain Jack’s adventure myself.

Someone far crazier had already attempted it.

For Humpy and the 1975 MecDec Bicentennial Committee, picking the horse was the easy part. A local owner and trainer was happy to provide a seven-year-old blood-red Arabian bay stallion. Named Sharek, the horse became an instant celebrity in the buildup to the bicentennial. At 850 pounds and fourteen hands high, every day in preparation for his marathon ride to Philly, Sharek consumed two gallons of oats, barley, and corn along with two bales of hay laced with calf manna protein. Expected to average twenty-five miles a day, Sharek, whose face was split by a racing strip of white hair, was outfitted with custom, diamond-strength tungsten carbide horseshoes for better grip on the pavement.

Finding a rider was another story.

There would be a small support crew riding along with “Jack” in a classic 1970s Partridge Family–style RV. To keep the ride as authentic as possible, however, Captain Jack 2.0 would be required to stay in period garb and tack, and all lodging and stabling would be done by 4-H groups along the route. As grueling and unglamorous as that sounds, Humpy still received seventy-two applications for the role of Captain Jack. When it came time for the live auditions, though, most riders struggled with the American Saddle-bred horse that was chosen specifically for the tryout because of its unruly size and demeanor.

Things were looking rather bleak, and the entire stunt seemed to be in jeopardy, when, in a scene straight out of a movie, in sauntered twenty-two-year-old Jerry Linker, a third-generation farrier who had been shoeing horses and riding bulls since he was nine. Oozing Rip Wheeler Yellowstone vibes, without asking permission Linker tore off the saddle, tossed it aside, and leapt up on the massive, stunned horse. After effortlessly commanding the suddenly submissive beast around the ring, Linker stopped on a dime in front of the judge’s dais, stood up on the horse’s back, and, to a chorus of gasps, dismounted with a backflip.

Humpy Wheeler was in love.

He had found his Captain Jack.

“Jerry was brash and totally bad to the bone, which is kinda how I had al- ways imagined what Captain Jack must have been like,” says Karen Linker, Jerry’s eighth (and final) wife. “To just stand up in a bar and go, ‘Sure, I’ll ride five hundred miles and risk my life for this cause. Why not?’ That was Jerry too. He was unnaturally strong. He was a frontier justice, Let’s Freakin’ Go kinda guy too. They totally picked the right guy for this ride—both times.”

In some ways Captain Jerry was every bit the legend Captain Jack was. He was supposed to grow a full beard for the 1975 ride but couldn’t because his cheeks were covered in scar tissue from a fire when he was sixteen. At eighteen a bull fell on him and crushed his spine. Scheduled for surgery, Jerry waltzed out of the hospital with the back of his gown flapping in the wind. He let his back heal on its own, which resulted in a curved and calcified spine that shrunk him by a full two inches.

Today, Jerry lives in a tiny apartment in Georgetown, Kentucky, with a long-since-retired horse trailer and truck parked out front. He’s only seventy. But just like that banged-up, rusted-out pickup of his, Jerry packed a ton of miles into those seventy years, and they seem to have finally caught up to him. After months of back-and-forth scheduling, we finally found a window to talk in person in between his bouts of Covid-19, a stroke, and surgeries to place a shunt in his brain. “Back then I didn’t believe in fear, and I didn’t believe in pain,” Jerry tells me. “Back then if it didn’t have two legs and was hot, or four legs and was wild, I didn’t want nothing to do with it.”

In the weeks leading up to his 1975 ride, Jerry was described by reporters as a trucker, a college student, a rodeo rider, a blacksmith, a horse trainer, and a salesman—none of which was completely true. A third of his family members back in Texas were said to be in jail, except his grandma, who was locked away in an asylum. Jerry was a standout quarterback in high school. But when he begged to skip his farm chores for a day to attend his football team’s award ceremony, family legend says his father decked him just for daring to make the request. Jerry got up, walked to the banquet, and never returned home. Of his seven marriages before he met Karen, the longest one lasted two years. The shortest, two weeks.

“At times, like with the MecDec, he did seem like a larger-than-life superhero, just a slightly deranged, schizoaffective, not necessarily all that pleasant superhero,” says his daughter Valerie Linker who, if you couldn’t tell, is studying psychology at the University of Kentucky. “He was very much the center of attention everywhere he went. So, naturally, he loved being Captain Jack. And he was great at it, he really was. I’m his daughter and I wouldn’t say I necessarily like him all the time, but even I have to admit he was pretty darn charming.”

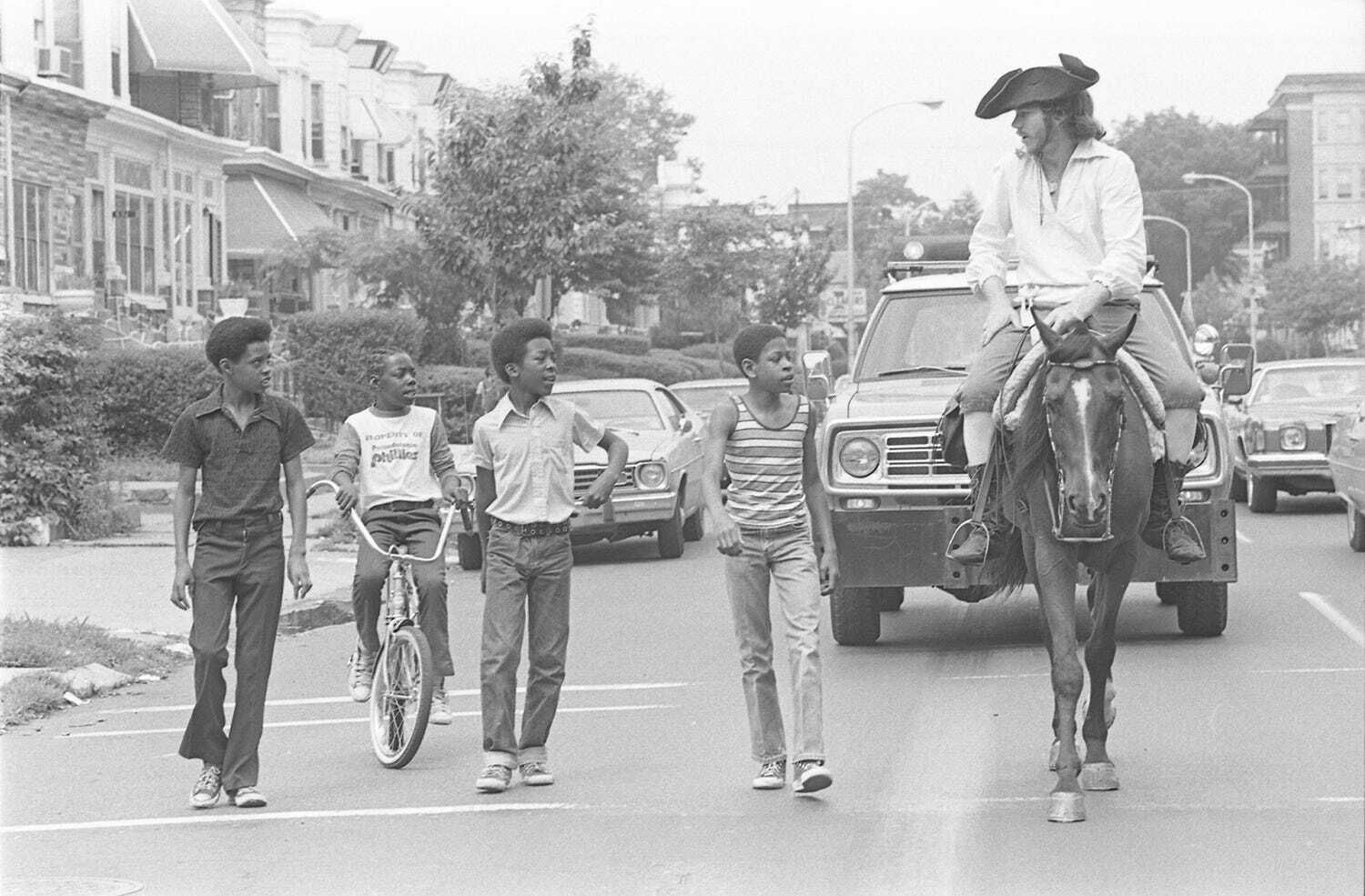

From the moment that backflip literally landed him the job, Linker was all-in on the role of his lifetime. For two months, he rode Sharek through downtown Charlotte to acclimate him to traffic, noise, and well-wishers. In preparation for his press conferences and public speaking along the route, Linker read all he could on Charlotte and the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. And to help him recover from the extreme heat, the committee stuffed his saddlebag with salts, potassium pills, and extra vitamins, which Linker may have occasionally supplemented with his own stash.

It was the ’70s, after all. And this poor guy had to sleep in farmhouses and ride an 850-pound horse down a highway shoulder for a month while looking like a member of the Village People in wool knee britches, a tri-cornered hat, and a puffy shirt. “Hated the outfit,” says Valerie. “Said it made him look like a sissy.” A new, up-and-coming Vegas oddsmaker named Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder gave Linker and Sharek only a fifty-fifty chance of completing the MecDec mission. “It’s hard to grasp how deadly it was what Captain Jack did. The British woulda killed him in a heartbeat, no questions asked,” says Jerry, who today looks like an older version of John Adams if he were on vacation at a dude ranch. “I just wanted to make it so that people could get a grip on what Captain Jack did for his country. I needed people to know that.”

As part of the bicentennial celebration, Humpy’s committee built a full-scale re-creation of the original Charlotte courthouse featuring a stair- case identical to the one where Thomas Polk formally proclaimed our in- dependence on May 20, 1775. Two hundred years and eleven days later, in front of fifty local dignitaries and the marching band from Independence High School, Linker stuffed a copy of the MecDec in his saddlebag and trotted off north on Tryon Street to Route 29 where, a few miles up the road, he and Sharek passed Sugaw Creek Presbyterian Church on their way to Winston-Salem.

Moments earlier, in a press conference before his departure, Linker, looking (and sounding) like a Revolutionary version of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Ronnie Van Zant, told reporters, “Now there’ll be some people who’ll think this is great. And they’ll be some people who’ll say, ‘Who in the hell is this turkey?’ But the people I’m worried about are the lunatics that don’t believe in the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. There’s no telling what they might do.”

He’d find out soon enough, just as soon as he and Sharek stepped foot into Thomas Jefferson’s home state of Virginia.

Both Captain Jack and Captain Jerry crossed into Virginia via the Dan River, but their routes diverged from there. Jack had no choice but to follow the only path available and ride northwest toward Big Lick (Roanoke) and then, following what’s I-81 today, up the Shenandoah Valley and through a loosely connected trail of Irish and Quaker communities toward Staunton and Winchester. In northern Virginia, when he reached the main section of the Great Wagon Road, about 150 miles west of his destination, Jack would have finally been able to exhale a tiny bit, blending in with the crowds of merchant wagons and livestock and making good time on what was the 1775 version of a superhighway. From there he would have headed east through Gettysburg, York, and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where his family first settled after fleeing Ireland.

After Linker crossed the Dan, he rode northeast through Halifax and Charlotte Court House, Virginia, where, soon enough, the herculean task of what he (and Captain Jack) had signed up for began to sink in. With fifteen appearances scheduled in Virginia, the sunburned Linker was spending up to fifteen hours a day in the saddle (more on days when he got lost, which was often), and he had already gone hoarse from spreading the news about the MecDec. Sharek was in similar shape. He had already worn through a set of tungsten horseshoes, was limping slightly after tripping in a pothole, and had begun to struggle with the increase in altitude.

“Jerry always said when the ride got rough, that’s when he really could feel Jack’s spirit right there with him,” says Karen Linker. “Jack was nothing special; what I mean is he was just a normal person who volunteered to do a job and risk his life for his country. Jerry really related to that. You talk about walking a mile in someone’s shoes? Try five hundred. Every day that passed he had more respect and admiration for what Captain Jack did and what he represented, and one of the reasons Jerry never even thought about quitting was it angered him so much that the world didn’t recognize and appreciate what Captain Jack had done.”

Trying to correct that would push Linker to the brink. The next obstacle came on June 11 when he arrived in Palmyra, south of Charlottesville, Virginia. In the morning he and Sharek were scheduled to ride eighteen miles for a ceremony at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s mountaintop plantation and national historic site. The detour was explained to reporters as a gesture of goodwill. Truth be told, Humpy couldn’t resist the chance to parade the first, true declaration of independence all over the manicured grounds of Jefferson’s beloved Monticello.

“That Humpy Wheeler, he’s slicker’n snot on a doorknob,” says Jerry.

When Linker arrived in his Revolutionary finest, the Monticello curator informed him of an obscure rule (perhaps written that morning) that prohibited people in colonial costume from entering the site or even being photographed with the president’s home in the background. Unwelcome at Monticello, Linker and a large crowd of local government officials, representatives from the Daughters of the American Revolution, and close to fifty 4-H members and MecDec groupies found refuge across the street in Michie Tavern, a place far more suited to Captain Jack and Captain Jerry anyway. (The pub opened in 1784 when Corporal William Michie returned from a tour at Valley Forge. And, says Valerie, “bars and bar fights were kind of my dad’s thing.”) Standing in the rain, Linker calmly read his copy of the MecDec to the assembled crowd of Virginians who then awarded him with two replica quill pens. The same kind of quills, one would assume, that Jefferson would have used while copying passages from the MecDec over to his own declaration draft.

The dust-up at Monticello didn’t quite garner the national attention the Charlotte MecDec bicentennial committee was hoping for. Two days later, near Culpeper, Virginia, with almost no press coverage, the ride halfway over, and Sharek badly in need of rest, Humpy Wheeler performed one of the greatest PR resuscitations of all time.

With its rolling green hills and endless white-fence ranches, Culpeper is the unofficial capital of Virginia horse country. Acting anonymously, it wasn’t that hard for Humpy to convince a local busybody and horse-loving humane officer to swear out an arrest warrant on Linker for “overriding” Sharek. “Whenever you needed dirt, Humpy knew exactly where to dig,” says Jerry. Linker and Sharek were both taken into custody. The local sheriff then con- firmed for the growing throng of media that the name on the arrest warrant was “John Doe Captain Jack.” (Humpy must have been dancing on top of his desk at this point.) Released after an hour in jail, Linker defiantly jumped on a borrowed Appaloosa and, facing a $1,000 fine and a year in prison, rode off triumphantly toward Leesburg, Virginia, on the Potomac. Meanwhile, a district court judge in Culpeper ordered that Sharek had to rest and recuperate until an independent veterinarian could examine him. The following day, when the doc reported the horse to be in good physical condition, the now-refreshed steed was put in a trailer and driven north to be reunited with Linker before he reached Gettysburg. The charges were then dropped.

“Humpy only told him later that he was the one who had him arrested because the ride wasn’t getting enough attention,” says Karen Linker. “I don’t think Jerry was very happy about that, but it sure worked. By the time he reached Pennsylvania it had reached national notoriety. For a while Jerry was famous-famous, ya know? Put it this way: he was famous enough to know that he hated being famous.”

After the Associated Press picked up on the saga—Arrest Delays Captain Jack’s Declaration of Independence Ride—Linker, Sharek, and the MecDec were front-page news across the country for several days. “The South returned to Gettysburg Tuesday, but this time there was no battle,” pro- claimed the Evening Sun in Hanover, Pennsylvania. “It returned in the form of Capt. James Jack, portrayed by Jerry Linker.” Bags of fan mail, mostly from school kids, started arriving in Charlotte for Sharek and Captain Jack. Now, when Linker stopped in Gettysburg or Chambersburg, where he laid a wreath on the grave of Colonial Army Colonel Patrick Jack, a relative of Captain Jack’s (and a fellow bar owner), there were several hundred fans waiting to greet him.

The ride was featured in Sports Illustrated, The Mike Douglas Show requested an appearance, and Linker was now on a first-name basis with President Gerald Ford. More importantly, the correct version of the MecDec story was finally being shared far and wide.

That week on the popular game show Hollywood Squares, one of the stars was asked “if a Declaration of Independence had been signed before the one in Philadelphia?”

They got it wrong.

The correct answer was “yes.”

With Linker’s six-hundred-mile journey nearing its end, a newspaper in Lancaster, Pennsylvania,noted that he was carrying copies of the MecDec, “the first declaration of independence by any Americans from Great Britain.” And in covering Linker’s arrival, even the Philadelphia Inquirer went on record, declaring, “Because Captain Jack was successful in his long ride, many of the Mecklenburg ideals were expressed in the Declaration of July 4, 1776.”

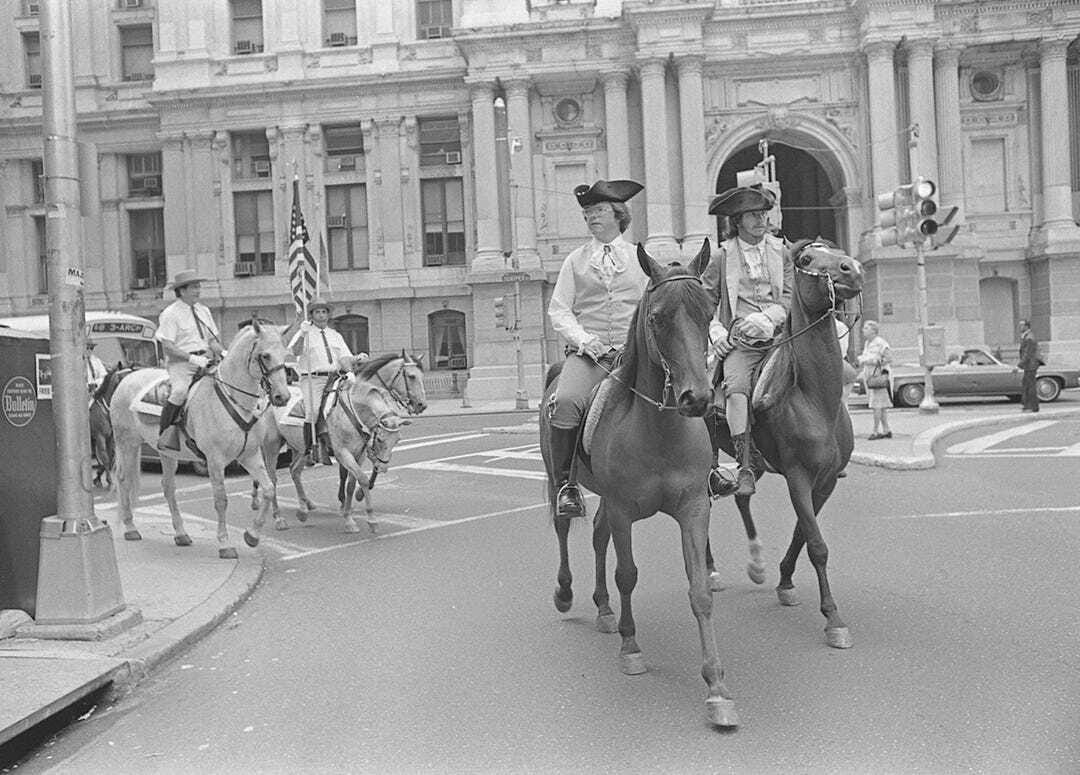

When Linker finally reached Independence Hall at 2:30 p.m. on June 29, 1975, a raucous crowd of 1,500 was there waiting in a steady rain to welcome Captain Jack 2.0 back to Philadelphia. Linker’s arrival was delayed slightly by an urgent pit stop at a Philadelphia hotel that tried to charge Captain Jack twenty-five cents to use the bathroom. “Me? I climbed over,” Linker laughs. Afterward, members of the 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Line, dressed in authentic red and blue colonial uniforms, saluted Linker with a deafening cannon blast. An emotional history buff in the crowd, using the lexicon of the times, put the entire scene perfectly into perspective. “This is really far out!” the guy shrieked as Linker climbed off Sharek, reached into his soggy saddlebag, and presented the MecDec to a handful of Philadelphia dignitaries.

Gentlemen . . . bear it in mind, the original Captain Jack declared in this same spot two hundred years earlier, Mecklenburg owes no allegiance to, and is separated from the Crown of Great Britain . . . forever.

Linker was then presented with an eight-inch replica of the Liberty Bell, which sits in his living room to this day. It was an appropriate gift since it was Thomas Polk who likely saved the Bell during the Battle of Germantown. In front of the media, whenever Linker could he deflected praise and attention back to the OG, Captain Jack himself. “He did it alone,” Linker reminded reporters. “And he could have lost his life at any minute.” It’s true, Jack had to constantly be on the lookout for Tories, whereas Jerry’s biggest concern was tractor trailers. Jack also had to turn around and ride all the way back home. A car would speed Linker back to Charlotte where he would be “knighted” for his service, and one of Sharek’s horseshoes would go on permanent display in City Hall. Another stark contrast between the two rides? While Sharek had lost some weight, Linker actually gained ten pounds thanks to the countless parade of people along the route who “were waiting in their yards with beer and lunches.”

But the most touching moment of the ceremony at Independence Hall in 1975 came when the rain started up again after Linker’s arrival. In a gesture that was indicative of the overwhelming gratitude and pride swelling up back home in North Carolina, when the skies opened up, Charlotte mayor John Belk quietly moved next to Linker and used his own umbrella to keep his city’s favorite son dry.

Mayor Belk’s act of brotherly love had accidentally blocked local press photographers from getting any good shots of Captain Jack, and before long someone in the press pool in front of the stage yelled out:

“Hey, you with the umbrella! GET OUTTA THE DAMN PICTURE!”

Linker and Belk shared a laugh at the authentic Philly-style welcome, the kind only Santa Claus at an Eagles game could truly appreciate.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can order David’s new book about his quest to uncover the true history of the MecDec by mashing the button below. (NOTE: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)