This edition of the Rabbit Hole was based on an episode of Away Message (now the North Carolina Rabbit Hole podcast) that I created in August 2017. If you’re not in the readin’ mood, you can listen to that episode here:

You want some Google Maps engagement bait? Well here it is:

I’m sorry, person on Twitter, you would like to know what goes on there? In the Great Dismal Swamp? Well let me, a person who has been there, start off with a shocker. This place is not nearly a great, dismal, or swampy as it once was. I know! Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, that place was much busier than you’d expect. Back then, the swamp was larger than the size of Rhode Island. Today, it’s a tenth of that size. Why?

George Washington, that’s why.

Not as Great

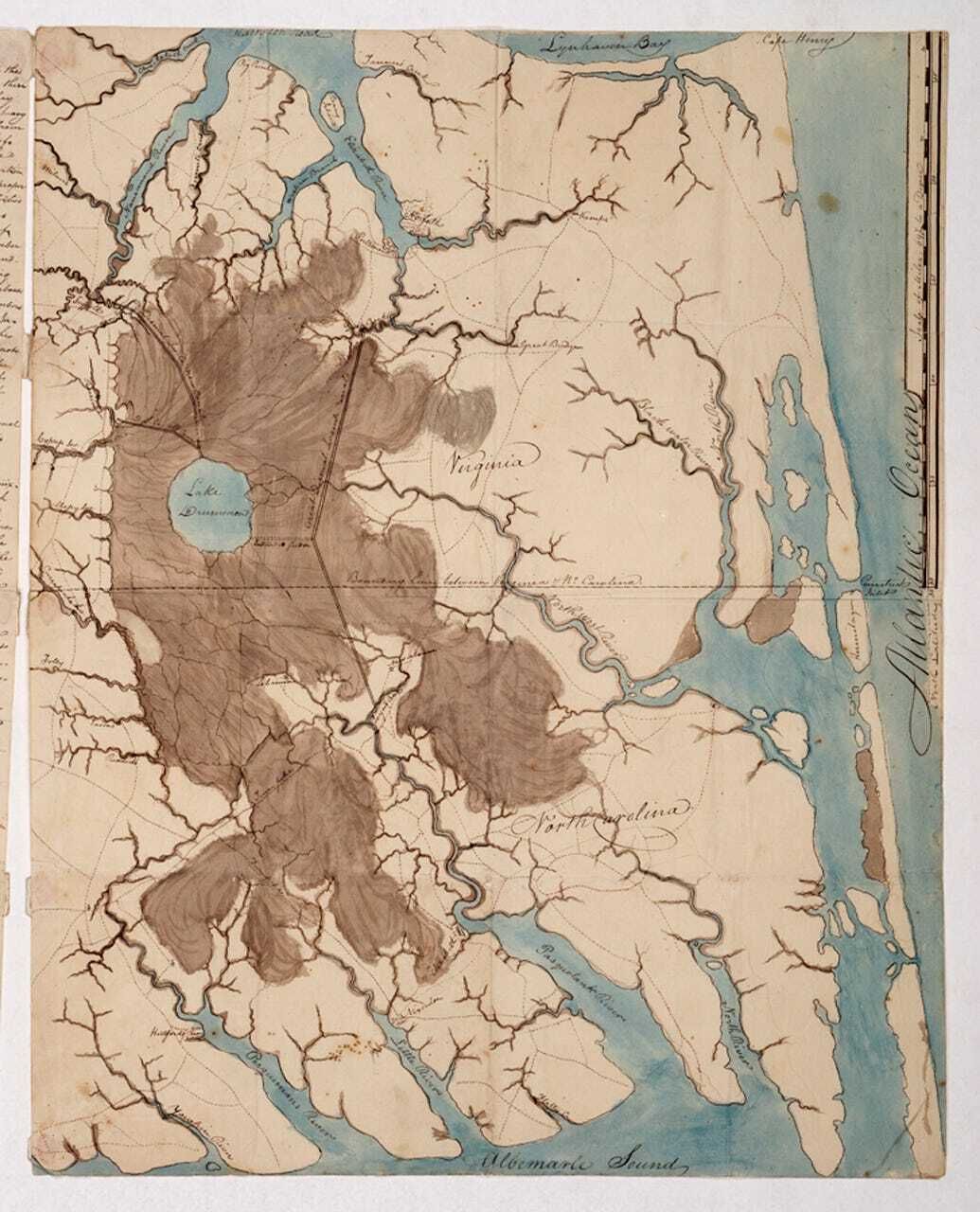

In 1763, long before he became president, Washington became an investor in the Dismal Swamp Company. The goal? Cut down trees, sell the logs, drain the swamp, turn it into farmland, and grow hemp. So the company used enslaved people to dig ditches and cut shingles from the cedar trees in the 1760s and 1770s, but the swamp didn’t, um, drain. Plus, the peat soil, which was made up of decomposed twigs and plants, wasn’t actually all that great for farming. Washington, who would go on to become busy with, uh, the whole Revolutionary War thing, later pushed for a canal to link the Chesapeake Bay and Albemarle Sound. Enslaved people dug that as well, and it opened in 1805. Eventually Washington gave up on the Dismal Swamp Company and sold off his shares in 1793, around halfway through his presidency.

In the long run, though, most of the land was drained and the cypress and cedar timber was sold off. As of 2022, the size of the swamp itself was only about 750 square miles across North Carolina and Virginia, a far cry from what it had been. In fact, most of what we today recognize as the Great Dismal Swamp is in Virginia. That includes Lake Drummond, which is the place most people associate with the area, and is one of only two natural freshwater lakes in the entire state.

So what happened to the rest of it? Well, big chunks of it did become farmland. Other parts are now neighborhoods in Suffolk, Norfolk, and Chesapeake, Virginia. You can see on a Google Map where the drainage ditches used to be in the Culpepper Landing neighborhood, which sits right next to the refuge and the canal.

In Culpepper Landing, the hand-dug ditches were filled in, but in a lot of other places they’re still intact. In fact, you can’t go too far in the refuge without seeing the literal scars of history—scars that were created by enslaved people, who later would see the swamp as a place where they could find their freedom.

Not as Dismal

Back in the day, the swamp had a reputation for being dismal. It’s in the name! William Byrd II, the fancy-pants Virginian in charge of surveying the North Carolina-Virginia border in 1728, was the first to refer to the area as the Great Dismal. It was “Great” because of its size: It once reached all the way to Virginia’s Back Bay. And “Dismal” because people often called swamps “dismals” at the time. Byrd himself called the Great Dismal “a miserable morass where nothing can inhabit.” (He also thought North Carolinians were lazy and ate too much barbecue). Byrd really hated the swamp, and his underling surveyors were mercilessly attacked by yellow biting flies, chiggers, and ticks, which are still quite present in the swamp today (I used so much bug spray during my visit in 2017.) Byrd, who was a real piece of work, didn’t join his men for this arduous journey through the swamp. He went around it.

Byrd’s view was consistent with the colonial, European view of the swamp. “They did a really good job of portraying it as a desert actually, as being devoid of life, as being uninhabitable,” Dr. Becca Peixotto, an archaeologist, told me during my visit. “It really wasn’t devoid of life as all.” There was plenty of wildlife and food in the swamp: turtles, frogs, fish, bears, birds, deer, paw paw, blackberries, wild rice, and more. “All of these things are available in the swamp if you know what you’re looking for and where to find it,” said Peixotto.

You know who knew where to find that stuff? Escaped enslaved people. Many of them were familiar with the swamps of West Africa, and knew that slave catchers wouldn’t go too far into the swamps to find them. Because of that, those escaped enslaved people, called maroons, went into the swamp to hide, and to live. Some built cabins. Others built entire communities. Some of them were only two miles from either a canal or the edge of the swamp.

Often, maroons interacted with the enslaved people that were sent into the swamp to cut shingles. “Sometimes these slave laborers would come back to their headquarters with way more shingles than any individual could turn up in that amount of time,” Peixotto told me. “That’s one way we know that the enslaved laborers and the maroons were working together out in the remote areas of the swamp. They would subcontract to get shingles made. And in return, the enslaved laborers might get supplies from the outside world like glass, or perhaps some food, or just the idea that their location where they were was going to be kept secret. A bit of protection.”

The story of the maroons in the Great Dismal Swamp wasn’t widely known. One problem with telling it: Maroons didn’t keep journals, and only a few of their stories were written down. But Peixotto and a team from American University led by Dr. Dan Sayers made a lot of trips to the swamp to learn what they could through digging.

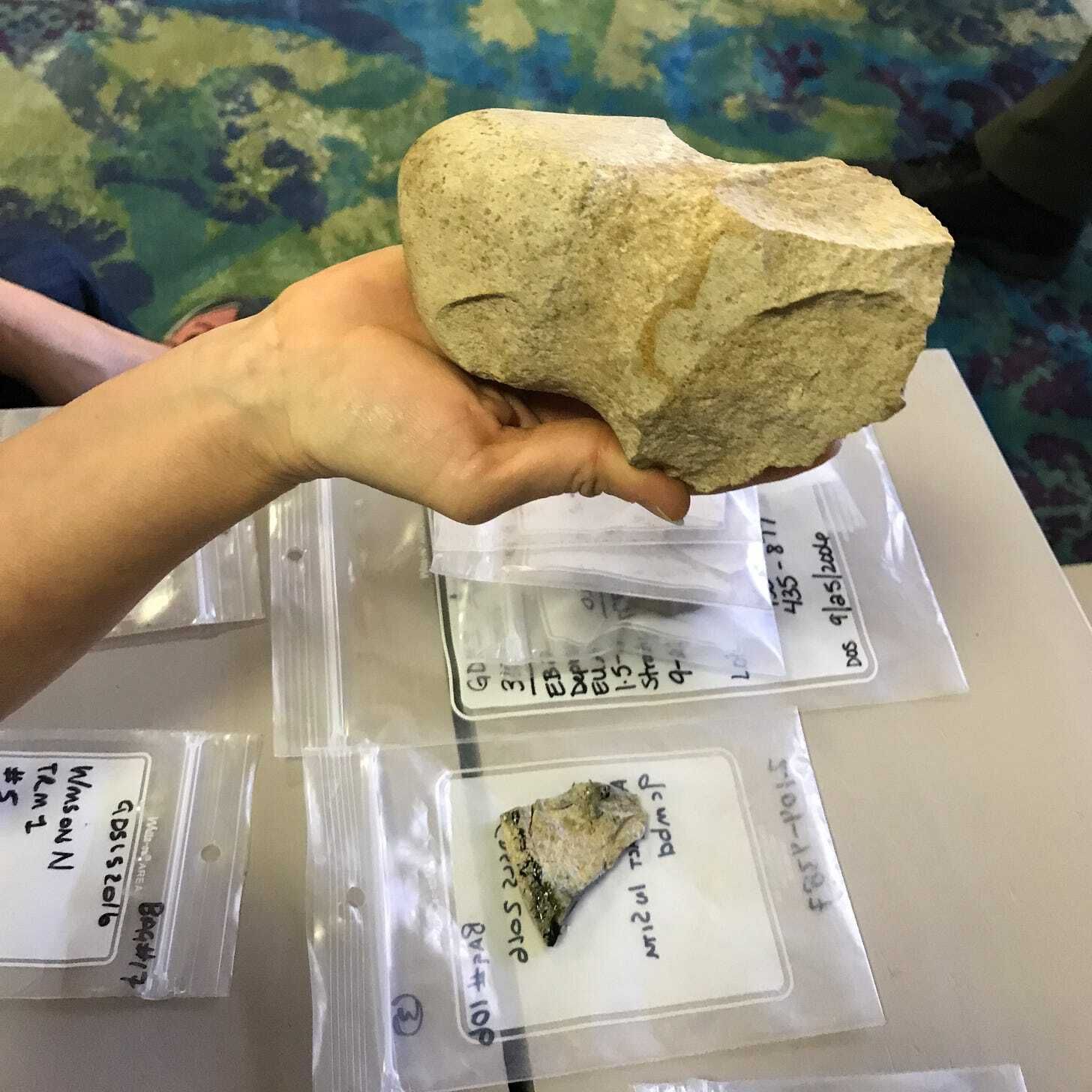

When we met in 2017, Peixotto opened a bag and pulled out meticulously-labled plastic baggies full of what seemed to be pebbles, shards, rocks, and flakes. How did she and her fellow archaeologists know that these little stone pieces were actually artifacts? “Any rock that’s in the swamp today had to have come from somewhere else,” she said. Rocks are found below the peat soil but not in or above it. Anything that looks like a rock is actually something that was carried in and left behind by someone who lived or hunted here.

Next question: How do you know where to dig? Peixotto laughed at this one. “You don’t?” she said. “In the swamp, it’s tricky. We look for islands because they’re the easiest to dig on. It’s very hard to dig where it’s wet and muddy.” Everything Peixotto laid out in front of me had been found in the top two inches of peat soil.

Some things, like a stone axe, were easy to identify. There were also nails, bits of scorched rock, and shards of glass. Peixotto got out a small piece of soapstone that had been carved into a pendant. “These are not just people who are worried about making projectile points to hunt,” she said. “They’re having families, they’re having lives, they’re having reasons for personal adornment and all of that.”

She flipped the soapstone in her hand. “You know, when we first excavated this soapstone pendant, the last person that touched it picked it up out of the ground was probably a maroon in the 1800s,” she said. “That’s an interesting connection to those people, whose lives I will never be able to understand. But I can hopefully interpret what we know about their lives in a way that other people can relate to, and see its importance in African-American history. In american history.”

Not as Swampy

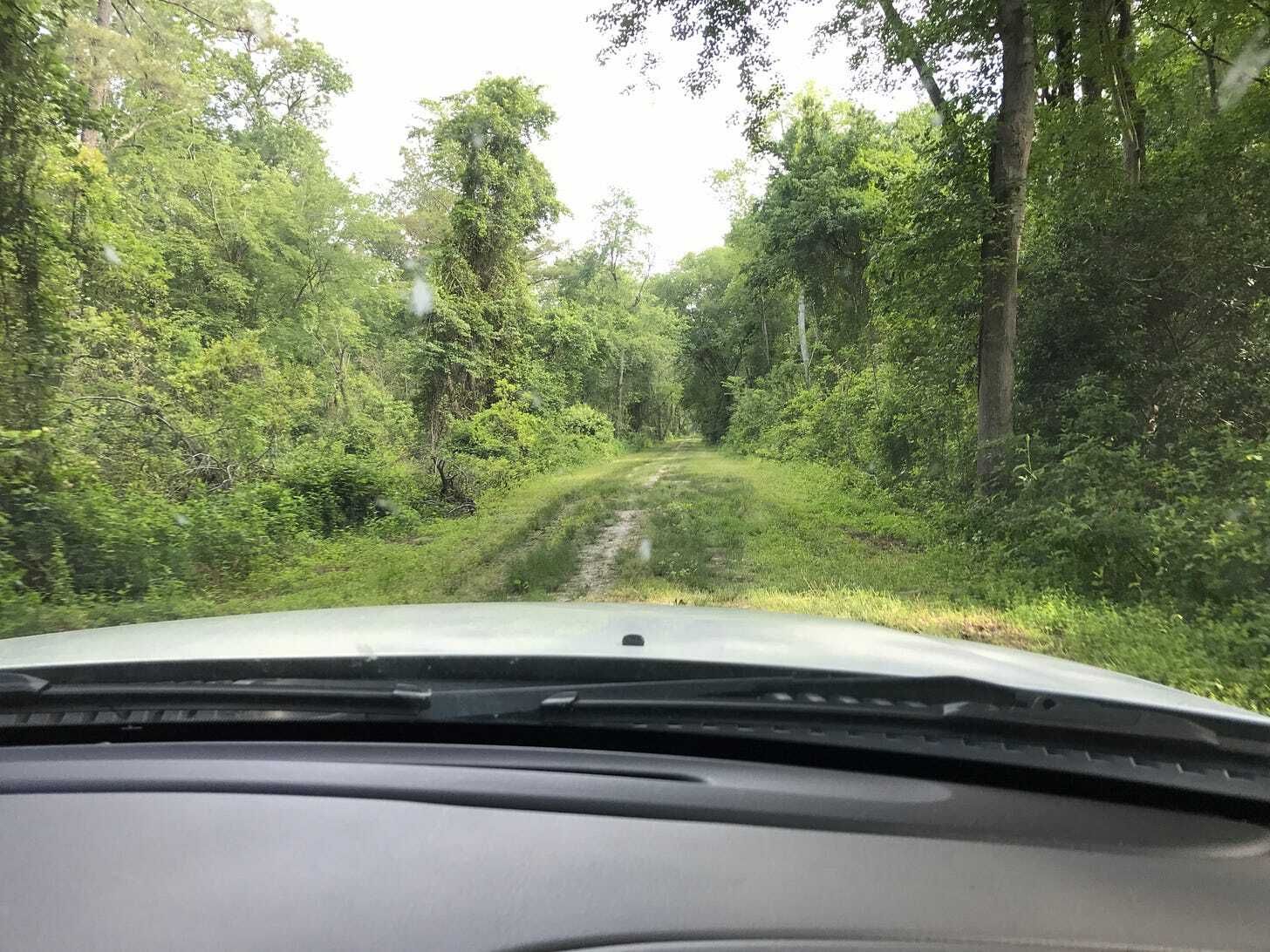

If you want a super-swampy swamp experience, Merchants Millpond State Park is probably the place to go, along with Congaree National Park down in (ew) South Carolina. You can find it in the North Carolina’s Dismal Swamp State Park too, but most of it looks like really thick woods. The trails in the park are mostly straight gravel roads, cut in next to some of the bigger drainage ditches.

That’s the initial view I got from the passenger seat of Adam Carver’s pickup truck back in 2017. Carver was (and still is) the park’s superintendent. “Great big cypress trees, great big cedar trees, that’s what the swamp used to be,” he told me. “It’s just not what it is today.”

Carver wanted to look for the remnants of an old rail line that was once used to haul logs out of the swamp. So we stopped the car and walked into the brush, which was incredibly thick and thorny. We swatted away yellow biting flies. I pulled at least four ticks off of me. A vine tangled itself around the gun strapped to Carver’s belt. I asked if the swamp has ever actually pulled the pistol out of his holster. “A couple times,” he said.

It took us 10 minutes to travel maybe 50 yards through the brush.

Of course, it’s not all gravel roads and thick brush. In another spot, Carver showed me a mature stand of extremely tall Atlantic white cedar trees. The sheer height of those trees meant they were at least 200 years old. They’re a rare find. They like the soggy peat soil, which felt spongy under my feet. After standing for a few moments, I’d sunken a few inches into the ground.

In the past, that peat soil has become a big problem. In August 2011, a lightning strike set off a huge wildfire on the Virginia side of the swamp The dried out peat soil was extremely flammable, and the fire basically burned down into the ground and created a gigantic six-foot-deep hole that butted up against the state line. At times, the smoke blanketed the entirety of Outer Banks on otherwise sunny days.

The fire burned for three months. Firefighters couldn’t really get back into the thickest areas to stop its spread. It was so persistent that even after Hurricane Irene dumped 10 to 15 inches of rain on the fire, it still wasn’t completely out. Smoke didn’t completely disappear until November, and the fire torched more than nine square miles in total.

It’s easy to see the remnants of that fire, even years later. Water has filled in the hole, which means the northern edge of the state park looks like a lake full of brush and ghost trees. “That peat soil is organic leaf matter and decaying trees,” Carver said. “It takes millions and millions of years to produce it, and in a matter of three months a fire comes through and it’s gone.”

That part isn’t really a swamp though. It’s more of a fire-made lake. In other parts, the state park and the wildlife refuge are trying to make the swamp swampy again. At one point, Carver showed me one of four metal dams in the park. He and the other rangers could put in metal slats, block up ditches, and hold water back. Black liquid pooled up behind one of them and a little bit flowed over the top and created foam thick enough to pick up. It looked like a Guinness-filled bubble bath.

Believe it or not, the water is really, really clean. The decaying vegetation in the swamp turns it black, and also puts tannic acid in the water, which keeps bacteria from living in it. One of Adam’s buddies, a tour guide, was known to dip a cup right in a canal, and take a big gulp of water.

You know who still isn’t convinced though? Kids. “Nine times out of ten their reaction is ‘Eeewwwww it’s black water! Look at the foam on top of the water! It looked like somebody peed on it!’” Carver told me. “And as soon as they say that, I turn around and ask them if they like sweet tea from Bojangles or Hardee’s or McDonalds or any of the fast food places that have sweet tea. Because sweet tea has the same tannic acid that the Dismal Swamp water has. If you take the lid off the sweet tea dispenser, it’s gonna have the same foam. That’s where it comes from, the tannic acid.”

(That isn’t even the funniest thing that people say to Carver. Some people have asked him if if there are sharks in the freshwater swamp. I wondered what Carver’s response was. “It’s hard to keep a straight face,” he said.)

You know what you don’t see a lot of in the Dismal Swamp State Park? People. During our deep trip into the swamp by truck (FYI, only rangers can drive through the park), the only people we saw were a few hikers within a half mile of the ranger station and visitor center, which sit on the other side of the main canal. There’s a lot of interesting stuff to see if you’re up for a hike and know what you’re looking for. But yes, it’s still buggy. And unless you’re already heading up U.S. Highway 17, it’s fairly remote. “In my opinion, that’s kinda the beauty of the Dismal Swamp,” Carver said. “You can go out there and not see anybody. And that’s what you need, to get away from everything.”