The best stock tip: Buy Food Lion shares in 1957, then forget all about them.

We're all talking about GameStop, but it turns out that one of the greatest investment opportunities in American history involved a grocery store chain that started in Salisbury.

NOTE: Twin powers unite! A shorter version of this story also appears in this morning’s edition of The Charlotte Ledger, a fantastic newsletter that provides essential and original business reporting, as well as updates on DaBaby’s living situation on Lake Norman. I wholeheartedly encourage you to subscribe here.

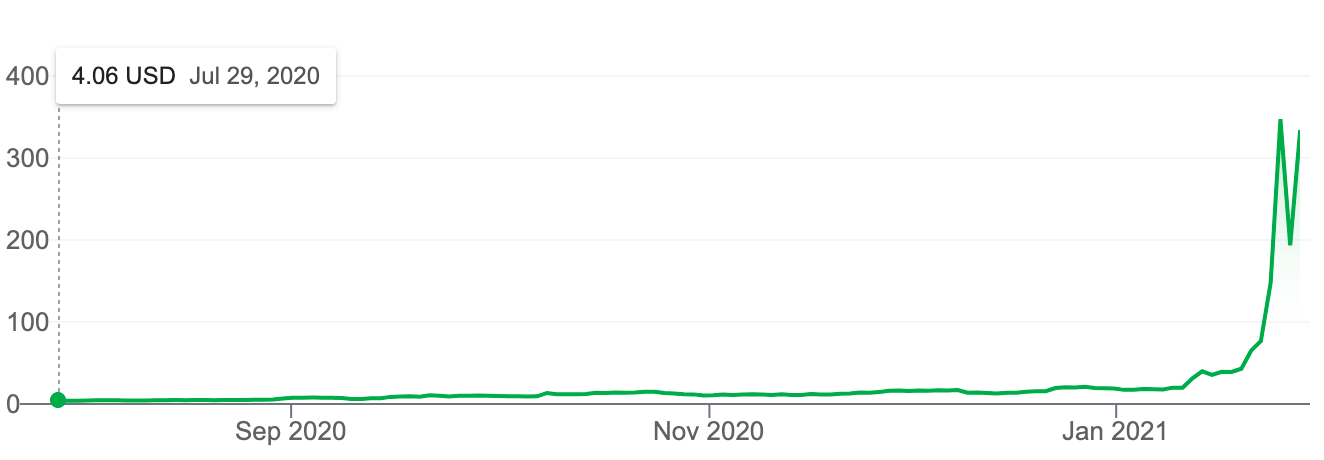

Back in August, I was in a GameStop for five minutes. I went in briefly to see if they had a good deal on used iPads. They did not. I left. If I had known then what I know now, I would have asked the teenager behind the counter if I could buy some shares of the company instead, because here is what has happened to GameStop’s stock price since the summer:

The short version is that some Wall Street hedge funds made financial bets against GameStop, so that the worse the company’s stock performed, the more money those hedge funds would make. In other words, they “shorted” GameStop stock. But the risk was that if GameStop were to start performing well, the losses for those hedge funds could be gigantic. Basically, if you own stock, you can only lose as much as you invest. But if you short a company, those losses can technically be infinite. (BUST Magazine did a quick Twitter thread explaining how shorting works using a Target dress as an example).

A while back, some folks on Reddit figured out a way to wreck those hedge funds while, at the same time, making gobs of money. They did this by convincing a lot of regular folks to use Robinhood and other apps to invest in GameStop. That sent the stock price soaring, which sent those hedge fund losses into the stratosphere. To keep from going bankrupt, those funds had to actually buy more GameStop shares, which caused the share price to go even higher. Hence the stock, which was trading at around $4 a share six months ago, has been somewhere around $300 lately, which made those Redditor investors (Invedditors? Reddistors?) a lot of money and caused billions of dollars in losses for hedge funds.

tl;dr - The GIF version of the GameStop story

Imagine hedge funds are Indiana Jones, the stone pedestal is GameStop, and the temple is the stock market. Dr. Jones is making a risky personal bet that by decreasing the value of the stone pedestal (by taking the priceless golden idol that sits on top and replacing it a bag of worthless sand), he can personally profit.

But the hedge funds don't know that the Redditors have set a trap underneath the pedestal, which then causes the market to react to Dr. Jones.

Jones narrowly escapes the temple with his life (barely outrunning the Large Rolling Boulder of Public Opinion), only to have to hand over the idol and any of its future profitability to René Belloq and the tribesmen waiting outside of the temple (the Redditors).

Just like in Raiders of the Lost Ark, there are still a lot of unknowns. We never actually find out whether Belloq can sell the idol for a profit. It’s possible that there is a glut of small, golden, South American statues already on the market. (A Chachapoyan Fertility Idol bubble!) The temple seems to have been left in shambles but still may be structurally intact on the whole. That would mean only bankrolled treasure hunters (wealthy investors) would henceforth have the resources and ability to get inside, shutting out potential future tourists (us regular Robinhood folk). The stone pedestal seems to have been ascribed some value (we’re all talking about the stone pedestal right now!), but will probably go back to being, well, a regular-ass stone pedestal again. And, to repeat, Dr. Jones is not dead. He still gets to go all over the world to plunder priceless antiquities for his personal profit and glory. Remember, he regroups from this and then steals the damn Ark of the Covenant.

That all seems insane. Is there a safer bet?

Index funds?

Boring. What else ya got?

Well, you could build a time machine out of a Delorean, go back to 1957, and invest a small amount of cash into Food Lion.

That’s impossible, yet exciting!

Well, it’s exciting now, but it wasn’t at the time. Back in 1957, a man named Ralph Ketner and his business partners wanted to open a grocery store in Salisbury, but didn’t know anyone who could give them a lot of money. So they started calling people they found in the phone book, asking if they might like to invest a little bit of cash in their new store. They started at $10 a share. Of the roughly 250 people Ketner and his partners called, about half of them bought in, including mill workers, a doctor, a builder, and a linotype operator. They took down names and amounts on a legal pad.

Food Lion (then Food Town) didn’t make much money at first. Then Ketner figured out that he could lower his prices and cut his overhead, and save by buying in bulk. Ketner later explained it by saying he’d rather make “five fast pennies instead of one slow nickel.” That low cost, no frills mantra made the company into a wholly inglorious place to work (executives never flew first class and Ketner had linoleum flooring installed in his office). It also transformed Food Lion into the fastest-growing grocery store chain in the country. What once was a small company with seven stores in 1967 added hundreds more over the next two decades. Sales grew 37% per year during that time. “It's a machine,” a stockbroker remarked to Fortune in 1988. “Year in, year out, with no variation. It's the most consistent growth company I've ever seen.”

To keep stock prices low to encourage more investment, Food Lion split its shares over and over again. That exponentially increased the amount of shares held by the people who’d originally bought in back in 1957. By 1988, the stock had split 12,960 ways. That meant anyone who’d bought and held on to at least $28 worth of original Food Lion stock was a millionaire. Some 87 people had.

It was one of the most insanely lucrative investments in American history, outperforming Walmart and Microsoft. The people Ketner picked out of a phone book became fabulously wealthy. Salisbury had more millionaires per capita than any other city in the country.

At one point, Ketner figured that one out of every four of those millionaires had no idea what they were worth. A few years ago, I wrote about the case of Zeda Barger for Our State magazine. Barger was an 81-year-old widow who, one day, got a visit from Ketner, who came to her house asking for a large donation to renovate a dorm at Catawba College.

“I don’t have any money,” she said. To get by, her sister had been sending her money to supplement her Social Security checks. Still, Barger knew who Ketner was. She and her late husband, a druggist named J.J., had made a $500 loan to Ketner way back in the summer of 1957, when Food Lion (then Food Town) was struggling to open its first grocery store in Salisbury.

“Zeda, you didn’t loan it to me,” Ketner said of the money. “You bought stock in the company.” That $500 was now worth $2.5 million. The original stock certificates had been sitting in her dresser drawer.

Barger’s name is still on a dorm at Catawba College today.

If you’ve been to Salisbury and are wondering why it seems so well preserved, Food Lion stock is why. Many of the original investors put their money back into town by making large investments or charitable donations. The gorgeous train depot downtown was preserved, in part, by money from Food Lion stock. Ketner himself built affordable housing. He renovated a 7-story building downtown. He donated 35 percent of his wealth before his death. Today, Salisbury, population 33,727, has a symphony orchestra. It has public art. Historic homes and landmarks have been preserved. Catawba College and the local hospital have all received large gifts of Food Lion stock. The Norvell Theater is named for Lucile Proctor Norvell, who called her shares her “givin’ away money.”

If you’re looking to get in on Food Lion’s meteoric growth, that time has passed. The company was bought in 1974 by Delhaize, a Belgian company that has since merged with Dutch-owned Ahold. The growth started to slow. The philosophy changed after Ralph Ketner’s retirement (he groused that executives had started flying around in private jets). All of the missing millionaires have been found, and many have died, which means their fortunes have either been donated or split up among family. Salisbury can no longer reliably rely on people with stock to help out around town. “The Food Lion era is coming to an end,” Ronnie Smith, a former shareholder and son of co-founder Wilson Smith, told me back in 2016.

But, literally, the best thing that could have possibly happened to you was to have bought a few shares in the early days of Food Lion, and then forgotten about them for the better part of two or three decades. As a Fortune reporter found back in 1988, not everybody did that:

Jim Woodson tired of pushing a mower around his two-acre backyard. Eyeing Food Lion's stock in the early 1970s, he thought, ''Maybe I can make a couple of dollars and buy me a nice riding mower.'' He bought about 400 shares, took several thousand dollars in profits shortly after, and, pleased with himself, bought the mower. Thus, the 72-year-old attorney's Food Lion tale became the saddest in Salisbury: That stock would be worth $3 million today. “I would think it's one of the most expensive riding lawn mowers in North Carolina,” he says laconically. At least it has run faultlessly. Says Woodson: “If it ever gives me any trouble, I think I'll call Ralph and ask him to have it fixed.”

So what you’re saying is, it paid off to ignore glittering, shiny stocks that offered quick payouts and instead stick it out with an unadorned company that was built to last.

Yes.

Is there a GIF for that?

—

I, Jeremy Markovich, am a journalist, writer, and producer based outside of Greensboro, North Carolina. I do not give actual investment advice. If you liked this, you might like Away Message, my podcast about North Carolina’s hard-to-find people, places, and things. Season 4 was all about the Mountains-to-Sea Trail.

Author avatar by Rich Barrett.

If you enjoyed this edition of the North Carolina Rabbit Hole, share it with your friends and mash that subscribe button below.