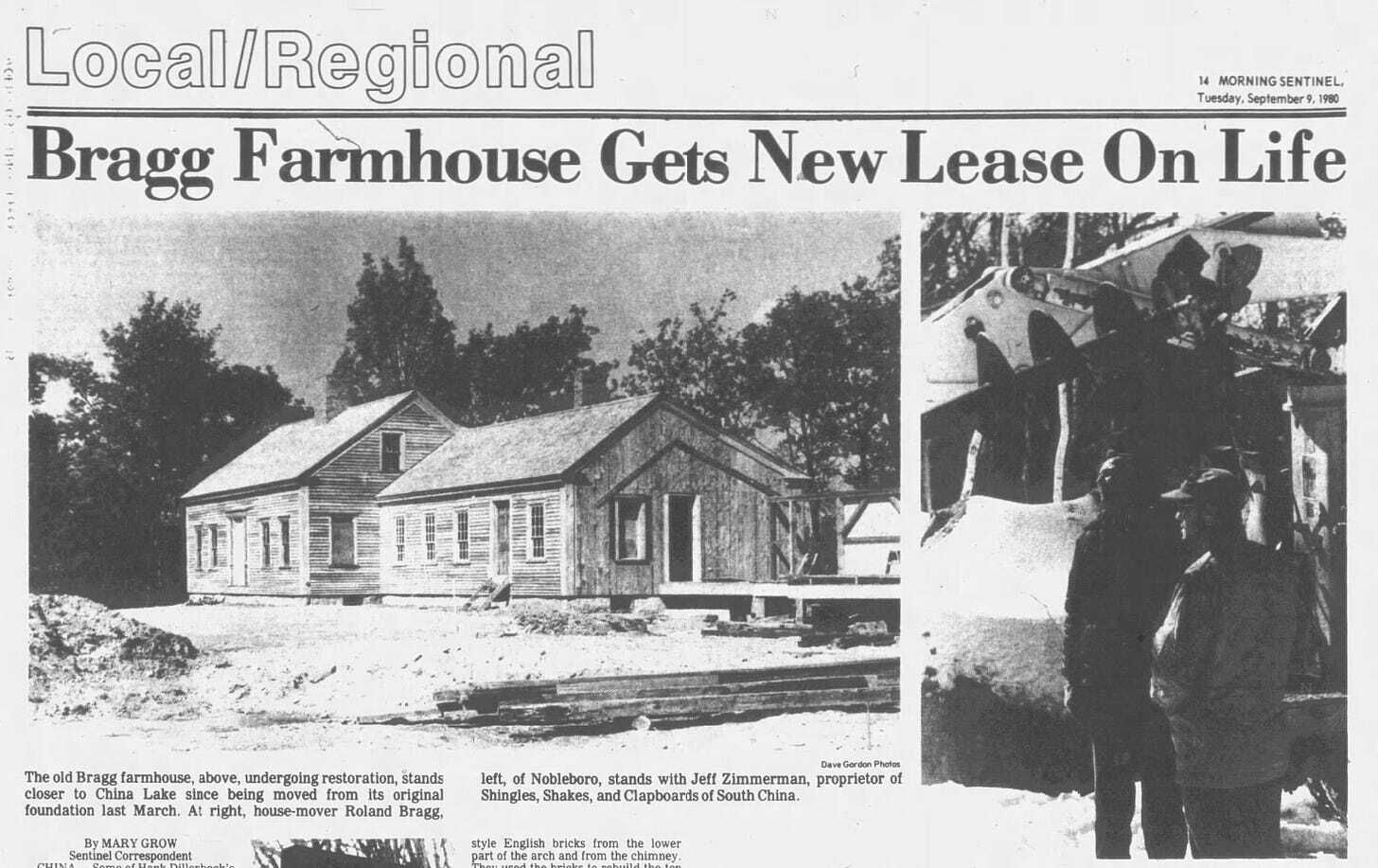

During his career, Roland Bragg was perhaps best known for moving a lot of houses. Not in the modern real estate investor sense of the word. He physically moved houses. Starting sometime in the 1950s, he founded what would become the Nobleboro Moving Company in Maine. The company also did demolition and construction, including the rebuilding of the Five Islands Wharf in Georgetown after a storm in the late 1970s. But it was the moving of buildings that got headlines across the state. Each job became a small-town spectacle, and Bragg would show up in the newspaper, directing traffic or driving a truck or staring at a house that was slowly creeping down the middle of a road. Bragg moved 60-ton houses. He moved old churches. The state trusted him to move a then 150-year-old barn in 1973. Once, in 1980, he cut a house into three pieces, trucked it down to the Rockland waterfront, loaded each piece on to a barge, then floated it over to its new home on the shore of Northeast Harbor. “We’ve moved bigger ones than this,” Bragg told the Bangor Daily News. “But we never moved one in three pieces before. No sweat.”

How did he decide to do this? To move houses for a living? He just … wanted to, says his daughter Debra Sokoll, who lives in a home that her father once relocated. He was a strong man with a strong mind, and “he decided he wanted to move buildings,” she says. Simple as that.

After he retired from the building-moving business, Bragg ran a portable sawmill. He also owned a body shop, and was a selectman in his hometown of Nobleboro, Maine, which has a population of around 1,800 people. Bragg was a Mason, a member of the American Legion, and ran the local Grange hall. He and his wife Barbara, the daughter of a former major league catcher, had three daughters. In the summers, their family would hold a big lobster and clam bake at their house. In the winters, Bragg would drag an old car hood down to a frozen pond. He cooked marshmallows and hot dogs on it while his kids skated. He loved spring flowers, even though he was color blind. “He was a gentle man, even though he could be stern at times,” Sokoll told me by phone. “He had to be stern because of World War II. He had PTSD.”

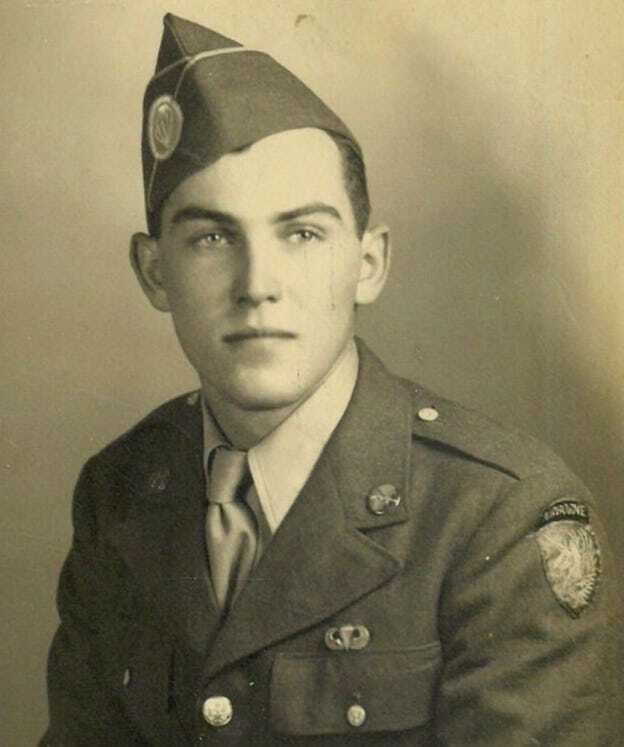

Bragg served for two years as a private first class, from 1943 until 1945. He was a paratrooper with the 17th Airborne. But for most of his life, he didn’t talk about it. Then one Christmas, in his later years, Bragg said he wanted to tell his family about his time in the Army. Sokoll perked up.

“He told us about how he stole a Jeep,” she says.

It happened after he’d been captured by the Nazis. One of his captors was a Mason. Bragg was a Mason. Upon learning that, German agree to let him go, as long as it looked like an escape. That soldier, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed German, told Bragg to hit him over the head as hard as he could. So he did. Bragg grabbed a Jeep, used it as an ambulance, and loaded up a bunch of wounded soldiers. He wore the German soldier’s uniform to get through enemy lines. “The Germans didn’t know he stole the Jeep,” Sokoll says. “And the Americans fired at him because they didn’t know he was an American!”

Bragg got the wounded men to a hospital, and then moved on. Later, when he read “The Bitter Woods,” a deep recounting of the Battle of the Bulge written by Dwight Eisenhower’s son John, he’d learned that all of those men had died. Even so, his actions earned him a Silver Star to go alongside his two Purple Hearts.

Fast forward to now. This week, Sokoll’s daughter Jennifer called her. “She said something about Fort Bragg being named after my father,” Sokoll says. “I thought it was a hoax.”

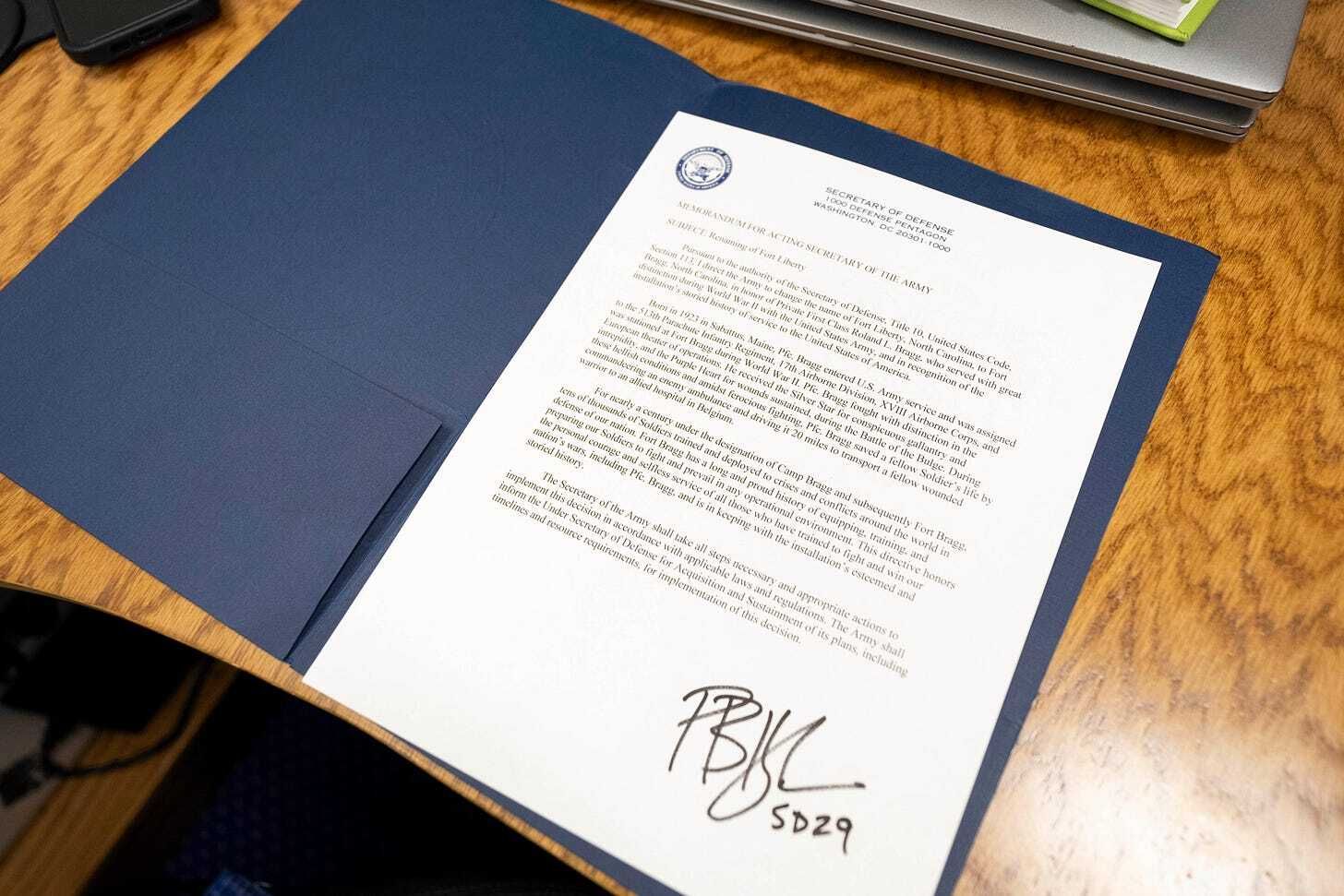

It was no hoax. On Monday, Former Fox News weekend morning anchor Pete Hegseth, in his new role as, uh, U.S. Secretary of Defense, signed an order changing the name of North Carolina’s Fort Liberty back to Fort Bragg, sort of. The full name will be Fort Roland L. Bragg. “That’s right,” Hegseth said in a video. “Bragg is back.”

Let me step back for a moment, because this story is going to be equal parts heartwarming and cynical. Heartwarming because it seems, by all accounts, that Roland Bragg lived a quiet, hard-working life in Maine, punctuated by a brief and amazing act of bravery. His World War II story is inspiring, selfless, and memorable, and it’s been great to see it spread.

And cynical because if Roland Bragg was, say, Roland Smith, you probably wouldn’t be reading this story at all. Circumstantial evidence would strongly suggest that Bragg’s last name is the main reason why he’s now the namesake of one of the world’s largest military installations. Hegseth and his boss, Donald Trump, have been saying for months that they wanted to bring the Fort Bragg name back. They were barred by law from using the base’s original Confederate namesake. To get around it, they found another soldier named Bragg.

Now look. I don’t know this for sure. I did, for the record, submit a Freedom of Information Act request with the Secretary of Defense’s Office for any records having to do with the re-naming. My request to expedite the processing was denied, and the Defense Department informs me that they have 4,675 requests to get to before mine.

It’s also safe to say that Roland Bragg wasn’t a well-known name in Army lore. Before a few days ago, hardly anyone outside of tiny little Nobleboro, Maine had ever heard of him. He died of cancer in 1999. His grave site is humble. There are no monuments or markers honoring him. The man who’s now the Bragg in Fort Bragg wasn’t notable enough to have a Wikipedia page before one was hastily thrown together the day after the announcement. Since the news broke, Debra Sokoll has gone through her house to find some old pictures of her dad, because the Army didn’t initially provide one to the public. She sent her husband Chris into town to have them scanned while he ran errands. Her phone’s been ringing off the hook. At 72, she said she’s had trouble remembering which stories she’s told to which reporter, although she did tell others that her father probably wouldn’t have sought out the honor.

So how did this happen? How did the Department of Defense find out about an amazing but obscure story about a soldier from Maine? Why did they change the name without telling the family first? Why now? Why him?

The First Bragg

First off, the original Bragg in Fort Bragg was a Confederate general. His name was Braxton Bragg, and nearly everybody agrees on one thing: He sucked.

In 2016, a historian tried to look at Braxton Bragg’s record and give him a fair shake. Sure, the historian wrote, Bragg was really disliked by his soldiers, colleagues, and superiors, but he wasn’t that bad of a military tactician. That said, the name of the book was “Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man in the Confederacy.”

Another Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest, supposedly called Bragg a coward. Even his own subordinates would troll him. Once, he lashed out at a private who had escaped from Union capture and came to tell him that the opposing army was retreating. “How would you know what a retreat looks like?” Bragg said sarcastically. “I should know,” the soldier supposedly replied, “I've been in your army almost two years.”

Bragg won a few battles but lost far more, and lost his post in 1863. After the war he sold life insurance and worked on the railroad before he died at age 59.

So how did that guy’s name end up on an U.S. Army base? Well, according to the Pentagon:

Some Army bases, established in the build-up and during World War I, were named for Confederate officers in an effort to court support from local populations in the South. That the men for whom the bases were named had taken up arms against the government they had sworn to defend was seen by some as a sign of reconciliation between the North and South. It was also the height of the Jim Crow Laws in the South, so there was no consideration for the feelings of African Americans who had to serve at bases named after men who fought to defend slavery.

A 1918 Raleigh News & Observer story said the new Camp Bragg near Fayetteville honored Bragg’s expertise as an artilleryman during the Mexican-American War. It also said that it helped that Bragg was born in Warren County, North Carolina, and was the only member of the Army from this state to become a Confederate general. The newspaper, which has since reckoned with its role in North Carolina’s white supremacy movement, seemed to be in favor of the name at the time. There was no mention of the fact that Bragg enslaved people.

The First Change

In 2020, after police killed George Floyd, the ensuing uproar led the Army to reexamine the places that were named for members of the Confederacy. Fort Bragg’s name change was mandated by Congress in 2021, when it passed a defense budget that legally decreed that all bases with Confederate names had to go. After that, the military set up a Naming Commission in 2022 and asked the public to submit some new names. They got more than 34,000 responses. There were presidents. Generals. Civil rights leaders. But the list also included Cher, Benedict Arnold, Harambe the gorilla, Dale Earnhardt, and yes, Chuck Norris.

Those thousands of names also included five people with the last name Bragg:

Edward S. Bragg, a “Wisconsin Civil War Officer, Lawyer, Politician, ‘War Democrat’, U.S. Congressman, and U.S. Ambassador.”

Janet Bragg, a groundbreaking Black pilot. During World War II, she was “instrumental in the U.S. Army Air Corps’ opening flight training for Black pilots at five locations, including Tuskegee Institute.”

Matt Bragg. There are a lot of dudes named Matt Bragg, including a public affairs specialist with the Marines and a member of the California National Guard. There’s also a Twitch streamer.

Roland L. Bragg, who you’ve heard about.

Thomas Bragg, a former North Carolina governor and U.S. Senator who became an attorney general for the Confederate States of America (which made him ineligible!). He was Braxton Bragg’s older brother.

The commission had to whittle down thousands of potential names to about a hundred. To do so, it said that the names shouldn’t refer to a living person, should be someone who served in the Army, and should not have the same last name as the person being replaced. (For what it’s worth, that last trick is exactly what the University of North Carolina used to rename its football stadium in 2018, changing its namesake from white supremacist William R. Kenan, Sr. to his son, William R. Kenan, Jr. Kenan Stadium became … Kenan Stadium.) Hence, no Braggs were named finalists.

In the end, an Army commission went with Fort Liberty, a name championed by Patti Elliott, a Gold Star mother from Youngsville, North Carolina whose son killed in Basra in 2011. It was the only base to be renamed for an idea, not a person.

Fort Liberty got a meh reaction from a lot of folks and was slow to catch on. Some people were glad so see Bragg gone, but wished the Army would have chosen a name like Ridgway or Porter instead. It didn’t matter. The military spent more than $8 million to change everything over to the new name in June 2023.

A Technicality

Fort Liberty immediately got condemnation from the “They won’t let you say that anymore” wing of the GOP. “We did win two world wars from Fort Bragg, right?” Donald Trump said during an October rally in Fayetteville. “We're gonna get it back. We're gonna bring our country back.” On his first day in his new job, Secretary Hegseth referred to Fort Liberty as Fort Bragg. “We should change it back, because legacy matters,” he said. “My uncle served at Bragg. I served at Bragg. It breaks a generational link.”

So how did the new administration’s Defense Department settle on the name of Roland Bragg? It’s unclear. An exclusive NBC News story from Feb. 7 by Courtney Kube and Mosheh Gains noted that the Army was exploring ways to change Fort Liberty’s name back to Bragg without breaking the 2021 law banning Confederate base names. “One option is to name the base after another soldier named Bragg, like Private First Class Roland Bragg, who was awarded the Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action while serving in the 17th Airborne Division during World War II,” the article stated.

Three days later, Hegseth changed the name to Fort Roland L. Bragg. He’s mentioned Roland, but has talked more about the return of the Bragg name. “I was honored to be able to put my signature on that [memorandum,] by the way, with the support of the president of the United States, who set the tone on this and said ‘I want Fort Bragg back,’” Hegseth told reporters on Tuesday. “It's about that legacy; it's about the connection to the community, to those who've served.”

Rhode Island Senator Jack Reed, a Democrat, called the change a “cynical maneuver” that violated the spirit of the law and associates “Private Bragg’s good name with a Confederate traitor.” Some former soldiers have mentioned that they’re glad the Bragg name is back without the overt Confederate baggage. The mayor of Fayetteville doesn’t like the change, saying it’ll cost a lot of money to change the name at a time when the new administration says it wants to save money. And Patti Elliott, who pushed for the Fort Liberty name, told the Associated Press she couldn’t comment due to the non-political nature of her position as a Gold Star mother. “Believe me, I have opinions,” she said, “but at this time, I have restrictions on voicing them.”

Again, it’s impossible to know at this point what led the Department of Defense to choose Roland Bragg (who, yes, was once stationed at Fort Bragg). But it’s possible that in the rush to put the name “Fort Bragg” back on signs, stationary, maps, and websites, officials decided to undo a thorough multi-year process via a loophole in the law, and hastily chose a name that someone saw in a news story or an old report. First they told the world. Then they told Roland Bragg’s family.

The Rest of the Story

Debra Sokoll says she’s happy that her father is being honored, but she doesn’t know all of the details. The Army did get in touch with her a day after it made the announcement, but she isn’t sure if the military will hold a ceremony. She probably wouldn’t be able to go. “I don’t travel anymore,” she says.

Also, she says, there’s more to her dad’s story.

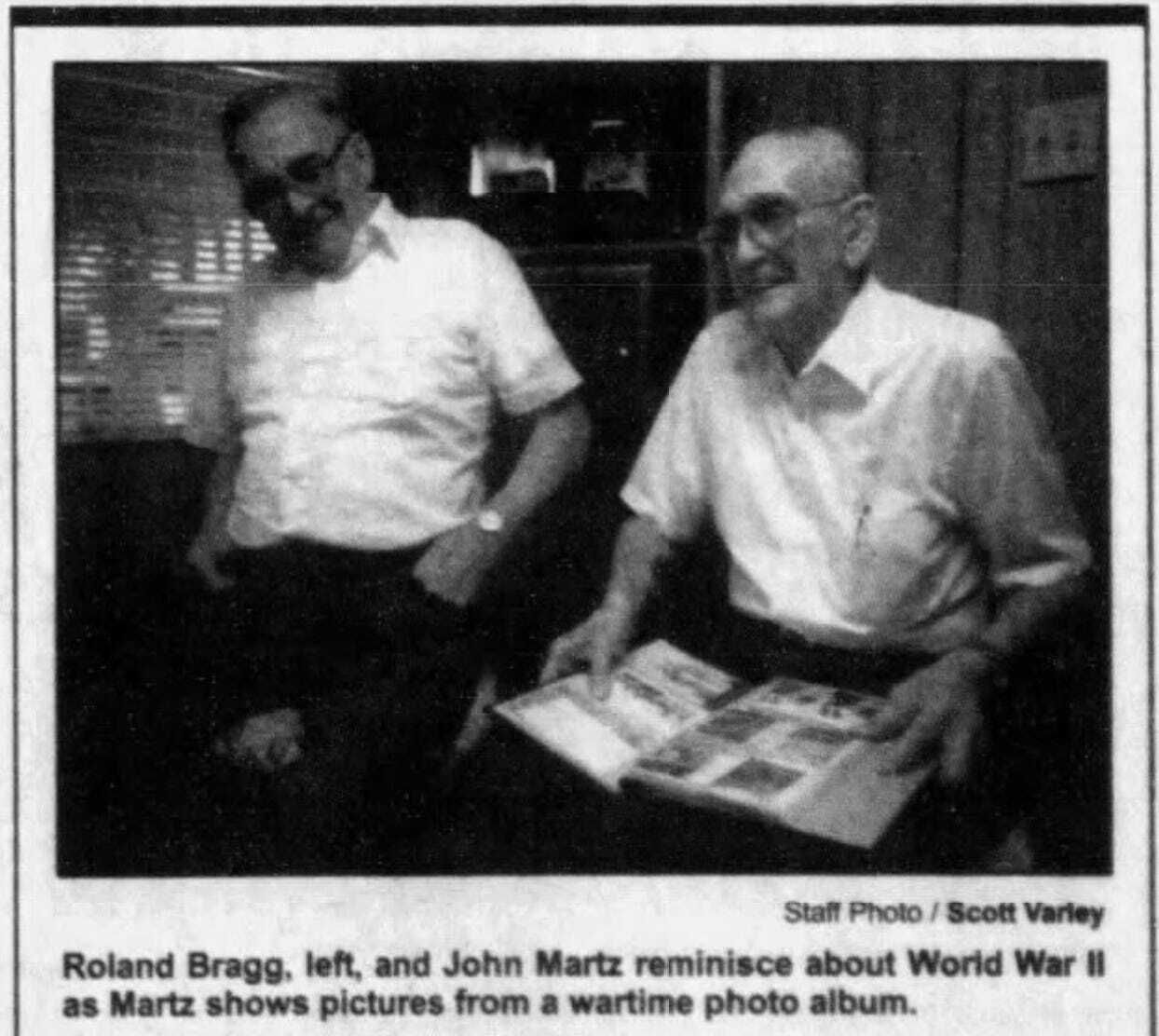

In 1993, Bragg got a piece of mail from California. “John [Martz] wrote a letter asking if I knew what happened to him,” he told a reporter for the North County Times in 1994. “I remember sitting at the kitchen table reading that letter, and the chills went up and down my spine.” John Eisenhower’s book had stated that everyone Bragg rescued during the Battle of the Bulge had died. For nearly 50 years, that’s what Bragg believed.

But it was wrong. Martz recounted lying in an old stone barn with three other wounded men. He and other members of the 17th Airborne had been hit by artillery fire and were running low on supplies. The other soldiers in his unit were moving out and had to leave him behind. He figured he’d be captured, if he lived. That’s when Bragg showed up with his stolen ambulance, loaded up the four men, and drove them 20 miles across enemy lines to safety. Thanks to Bragg, Martz lived.

The two men met face-to-face in 1994 at Martz’s home in California. They both admitted that they’d never spoken much about the war until they reunited. The reunion triggered old memories. “At that point my father started talking more to us about his war experience,” Linda French, Bragg’s late daughter, recounted in his obituary in 1999. “It opened up a dam.”

The experience also seems to have opened up a dam for Debra Sokoll. During our half-hour conversation, she talks a little about his military service, but mostly about his life in Maine. About her life. About her family memories. About what things are like in Nobleboro, and about what kind of a man Roland Bragg was.

Before I hang up, I ask her if she knows why Fort Bragg is being named for her dad. She pauses briefly. “I think he was a hero,” she says.