NOTE: Kids, we’re gonna swear today. A lot.

Earlier this month, I got an email from Ashevegas’s Jason Sandford, who asked me if I’d “ever written about a famous speech given in 1973 by N.C. Rep. Herbert Hyde of Buncombe County, who argued that it should be legal to cuss in Swain County.” No! I had not! For what it’s worth, I’ve been to Bryson City a few times, and nobody there has ever tried to swear at me. Those folks seem real damn nice.

But still. I did not know that a state senator once rose to passionately defend the right to drop expletives across a small swath of the Great Smoky Mountains. I also didn’t know that, at one point, profanity was considered to be illegal across 98 of North Carolina’s 100 counties. I was surprised … a little. A lot of the oldest laws on the books are a direct line to North Carolina’s old-timey Bible Belt past. This is, as I’ve explained before, the reason why we still have to deal with this state’s weird-ass system of state-run liquor stores. It’s also why our state constitution still says you have to believe in “Almighty God” to hold public office, even though Supreme Court cases have neutered that particular section.

It would seem like a law that made it illegal to swear in public would be unconstitutional, what with the First Amendment and all. But no! This particular law, which banned profanity on public roads and highways in North Carolina, was on the books for 102 years and enforced (albeit sporadically) for most of that time. During that period, some folks slowly but successfully made it applicable to more people, while others called for it to be tossed out entirely. And yet, for a century, it remained.

It’s worth talking about the legality of profanity now, mostly because cussin’ is having a moment. Politicians, who could once have rightly considered a publicly-delivered f-bomb to be a career-ender, are now dropping them because regular words fail to convey the right level of anger or urgency. Earlier this month, Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey told ICE to “get the fuck out” of his city after federal agents shot and killed Renee Good, calling ICE’s side of the story “bullshit.” President Trump, who has talked about “shithole countries,” may have made it possible for other public figures to respond with what was once considered to be profanity, especially angry Democrats. "If … Trump opened the door to swearing, Trump is getting a dose of that back now because other people are swearing to express their frustration at things they believe he's responsible for," Michael Adams, an English professor at Indiana University Bloomington and the author of "In Praise of Profanity,” told Axios.

It’s not just politicians. People are using profanity more often in movies and films, according to one study, which notes that f-bombs are deployed to show emphasis and emotion, or to demonstrate informality and camaraderie. Two years ago, linguistics experts told The Guardian that swearing was becoming much more socially acceptable. One, Robbie Love of Aston University, noted that words aren’t inherently bad—it just depends what you do with them. “If I say, ‘who the fuck did that?’, as opposed to ‘who did that?’, what does ‘fuck’ actually mean?” he said. “It’s just emphasising the general sentiment.”

So sure, things are different now. But how, exactly, did North Carolina end up with an anti-cussing law in the first place? Why did it hold on so long? Who finally made it go away? Get ready, you’re gonna hear all about it, along with some fantastic swearing. As the youths say, let’s fucking go.

Clean Living Through Clean Language

In January of 1913, William Devin introduced a bill that he thought would make the roads of his county safer. Devin was 41 years old, a former mayor of Oxford, North Carolina who’d been a lawyer in town for more than a decade and was well known in both legal and military circles. Locals referred to him as captain. Later that year, he left the General Assembly after he was appointed as a superior court judge, and would go on to become chief justice of the state Supreme Court. Lake Devin, which was created in 1954 to supply Oxford with water, is named for him.

But in 1913, Captain Devin was a member of the state house of representatives who seemed concerned mostly with taking care of local issues (and, occasionally, making speeches on the house floor about the life and times of Robert E. Lee). Early in the session, he introduced legislation that would “prohibit boisterous, profane, and obscene language” on the roads in Granville County. The idea, according to newspaper accounts, was to make the highways safer near his home. The Committee on Propositions and Grievances (!) recommended it to the full house for a vote.

But word got out about the bill, and a bunch of other representatives rushed to have their counties included as well. Within a few weeks, a bill that would have banned swearing on the public highways of a small county near the Virginia border was expanded to include the entire state. Just as quickly, other lawmakers asked for their counties to be left out. Hence, the bill that passed on March 3, 1913 made profanity on public roads (as long as it was in the presence of two or more people) a misdemeanor, but it also exempted 21 counties across the state, from the Outer Banks to the mountains. The lawmaker who got the bill across the finish line, Senator Quincy Nimocks of Fayetteville, was also overly concerned with swearing. In that same session, he also helped pass a bill to make it illegal to swear at “any female telephone operator.”

Neither man left behind any clues as to why they felt so compelled to ban swearing with a state law, but it came it at a time when there were organized anti-profanity movements across the country. “At the dawn of the 20th century, a growing number of Americans viewed public profanity not just as a social nuisance but as a threat to the nation's moral fabric,” writes Evan J. Christensen, a student at the University of New Hampshire who researched anti-profanity leagues. In the early 1900s, seemingly everybody was cussing. Sailors, soldiers, and mechanics used “loud and boisterous” profanity. Others swore to express both joy and anger. Women did it. Kids said some “exceedingly evil” words and phrases. Farmers were swearing at their cows. Fishermen cussed at their lines. Workers swore at their bosses. Actors cussed in plays. “It was noted that some swore naturally, others from provocation, some without provocation, and others seemingly ‘for the love of it,’” writes Christensen.

What counted as profanity then? Mostly the stuff we consider to be “swear words” today, along with religiously-tinged exclamations like “Jesus H. Christ!” or “Oh God!” Churches, as arbiters of morality, had always seen themselves as referees of proper language. But they really found their footing in the Progressive Era, whose leaders wanted to fix society’s ills. The enormous boom in things like industrialization and the growth of cities also led to questions about inequality and morality. That led to social justice, the public good, and labor rights being seen as good things during a time when Teddy Roosevelt was out there doing stuff like creating national parks. (The South’s version of Progressivism also led to things like “separate but equal,” poll taxes and literacy tests, and other legalized segregation). Morality was also having a moment, and a bunch of “anti” societies popped up to get rid of vices and offer temperance instead. The Anti-Saloon league led, eventually, to prohibition. Anti-imperialism movements sought to stop American colonization. Anti-evolution folks sought to stop scientific discoveries from overwhelming the old teachings of the church (See: the Scopes Monkey Trial).

And then there were the Anti-Profanity Leagues, which were pitched as a way to restore morality to the way people spoke. They’d been around since the mid-1800s, led mainly by preachers, but really started to take off in the early 20th century. Students got involved. People began to distribute leaflets, postcards, and signs urging people not to swear. Some leagues told women not to marry a man who cussed. “By saturating public and private spaces with visual reminders of moral discipline, anti-profanity leagues aimed to make clean speech a civic expectation,” writes Christensen. Teddy Roosevelt himself was a fan of Anti-Profanity Leagues.

The effect? People started to get scolded whenever they swore in public. Newspapers across the country ran stories complaining about “obscene language.” Cussing was seen as a moral weakness. An article in a paper in Asheboro in 1915 stated that “profanity is a useless waste of words.” Another story from Asheville said the Anti-Profanity League should go after the throngs of people who were swearing while caught in ever-increasing traffic jams on Liberty Street.

The no-cussing-on-the-road law, which threatened a $50 fine and 30 days in jail, began to be enforced, along with any number of local anti-swearing ordinances. In 1913, a Black man was arrested for using “profane language” in front of women in a store in Asheville (the store owner, who hit that man with a brick, was not charged). In 1920, two white men were arrested in Greensboro for swearing in front of women on a streetcar. In many other cases, a profanity charge was tacked on to something more serious. In 1922, Charlotte’s police chief was charged with assault, and prosecutors topped it off with a profanity charge. The chief replied he didn’t swear, but merely said that if someone slandered him, he’d kill them. And in 1933, a man accused a Charlotte police officer of swearing in front of women at the police station. The officer then confronted his accuser, who said “you keep your damn mouth out of my business.” The officer then arrested his accuser and charged him with … using profanity.

Over the years, more and more cities and towns passed ordinances banning profanity, and more and more counties opted into the state profanity law, often at the request of the local sheriff. A sponsor of one bill stated, in 1973, that the lack of a statue in her county “was being abused by people who erroneously thought it to be legal to curse anyone, especially law enforcement.” At one point, local leaders in Asheboro toyed around with an idea to add road signs at the county line that read “Entering Randolph County—stop cussing.”

By 2010, all but two counties (Pitt and Swain) had banned profanity on roads and highways. And then a woman in Chapel Hill changed everything. How? By calling some cops assholes.

Accidentally Challenging the Law By Swearing At The Cops

Most of what we know about Samantha Elabanjo comes from the court filings of lawsuits that she’s filed over the last two decades. She described herself, in a since-dismissed lawsuit against her former apartment complex, of having “depression, post-traumatic stress disorder ("PTSD"), bipolar disorder, and paranoia.” In 2008, she was arrested in Chapel Hill after she and a man were walking past I Love New York Pizza on Franklin Street, and started swearing at the people inside. When the police showed up, she walked out into the street and held up traffic. In court, she represented herself and was successful in getting the drunk and disorderly charge thrown out, but court later dismissed her lawsuit, which accused officers of roughing her up while trying to drag her out of their squad car. Two years later, in 2010, one of the same officers heard Elabanjo yelling and screaming at a bus stop on Columbia Avenue. The police told her to stop yelling in front of the kids nearby and move along. When they started to pull away, Elabanjo was walking in the street and told them to “leave me alone and go wash your damn dirty car.” After she got back to the sidewalk, she called the officers assholes. They wheeled around and promptly arrested her for disorderly conduct at a terminal and, you guessed it, using profane language on a highway.

In district court, the disorderly conduct charge was thrown out, but Elabanjo was convicted of using profanity. At this point, the ACLU got involved. On appeal, Superior Court Judge Allan Baddour found that it didn’t matter that Elabanjo called the cops assholes, because she was on the sidewalk and not on the roadway when she said it. That left the word “damn.” From Baddour’s ruling:

N.C.G.S. Sect. 14-97 defines neither "indecent" nor "profane," and thus leaves to the imagination, or an officer's discretion, what those terms mean, and which words, used in what context, would be prohibited. There is no longer any consensus, if there ever was, on what words in the modern American lexicon are "indecent" or "profane." A reasonable person cannot be certain before she acts that her language is not violative of this law, and it is therefore unconstitutionally vague.

Is “damn” a swear word? In this era? Yes? No? If you can’t agree that it’s profanity, then how can you be charged with a crime for saying it?

Baddour dismissed Elabanjo’s case in January 2011. “We are lucky to live in a country in which even offensive and unpopular statements constitute protected speech, as the alternative is a country in which conformity is required and dissent is not tolerated,” said Matthew Quinn, who represented Elabanjo for the ACLU.

Four years later, in 2015, the General Assembly quietly repealed the law.

So if it was fairly easy to get a judge to agree that it was unconstitutional, then why did the law stick around for so long?

F-Bombs By The Baker’s Dozen

For that part, I’d like to refer you to a delightfully-written entry in the First Amendment Law Journal, written by a then-student at UNC Law School named Alexandra Bachman. The piece, entitled “WTF? First Amendment Implications of Policing Profanity” starts off with Bachman describing her childhood love of swearing, which was inspired by George Carlin. Her parents didn’t like it. But also, she realized that her parents could not convict her in a court of law:

The good news is that we were all mostly right: saying bad words is not a one-way ticket to jail. The bad news is, until 2011, North Carolina had a statute saying the opposite: it was a misdemeanor to use “indecent or profane language” in public. The worse news, at least for anyone in Virginia, is that the use of profanity in public is still a criminal offense. Fuck that.

Well then! Bachman goes on to say that anti-profanity laws have their roots in common law, which has prohibited it in public spaces for centuries. In more modern times, the case for morality in language has run head-first into the brick wall of the First Amendment, which says you can’t ban words just because you don’t like them. The best defense of anti-profanity statues, at least in the eyes of the law, comes when they could be considered “fighting words,” which doesn’t get as much free speech protection in the eyes of the courts. In other words, if you yell “bitchy bastard!” in no particular direction among a crowd of people, then you, sir (or ma’am), are going to be just fine. If you keep calling someone a “bitchy bastard” because you would like to get them angry enough to fight you, then you may not be on solid legal footing.

For what it’s worth, plenty of other states still have anti-profanity laws on the books, and some have stood up to legal review. South Carolina’s law, which bans obscene language on roads and near churches, was used to arrest a woman who called the cops to help her get her keys back to a family member. While there, an officer heard her say “This is some motherfucking shit.” At the time, her house was 50 to 60 yards away from a church, which meant people there, supposedly, would be able to hear her. Her later conviction was upheld by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2016, which said the law wasn’t too broad or vague to be unconstitutional because it only applied to fighting words.

That said, Bachman summed up the issue in her law review piece (which melodiously uses some form of the word “fuck” 13 times):

For three key reasons, anti-profanity statutes are fucking ridiculous. First and foremost, they are blatantly unconstitutional. In a perfect world, unconstitutional laws wouldn’t exist, but in our world, shit happens. Second, anti-profanity statutes remain on the books because they are not a legislative priority and rarely get their day in court … Finally, state residents would benefit from uninhibited use of profanity.

I contacted Bachman, who graduated in 2019 and was a winner of the inaugural James R. Cleary Prize for her article. She didn’t have much to add, and notes that she practices a different form of law now. But! “As a human, I wholeheartedly believe that censorship is a stepping-stone to tyranny,” she wrote in her article. “As a product of these many considerations, I say ‘fuck you’ to anyone who tells me profanity is un-ladylike, inappropriate, or against the law.” Goddamn!

So, can you swear without consequences in North Carolina now? Nope! In 2015, an 18-year-old in High Point was arrested for shouting “fuck the police” as he passed a traffic stop (the charge, according to news reports, was an utterance to provoke a violent retaliation). And, as we all know, you can do things that are technically legal and still have consequences at work. In 2016, a teacher in Durham was suspended for swearing at her kids in class:

As of now, it’s still illegal to swear at someone on the phone in this state, and you’re not allowed to cuss in the presence of a dead body, which is a law aimed at keeping order at funeral homes and memorial services. Challenging either one in court might be hard, since the latter one would require you to shout something like “look at this shit-ass bastard” at a casket. Repealing either statue would also be tough because, as Bachman noted, “conservatives fear change, profanity, or both”, and getting lawmakers to repeal a law is a tall fucking order.

Profanity vs. Absurdity

In the end, the one thing that seems to work against the fighters of profanity are the warriors of absurdity. Which brings us back to Rep. Herbert Hyde of Buncombe County. In 1973, a state senator, Bette Anne Wilkie, had introduced a bill that would add Swain County to the list of counties where swearing was banned on the roads. It was then, that Rep. Hyde got up to speak. “If I sound humorous, don’t take it that way,” he told his fellow lawmakers. “I’m dead serious about this.”

What followed was the driest, folksiest, and greatest legislative standup routine that’s ever been performed on the floor of the North Carolina House. Over the course of eight minutes, Hyde opined that he might introduce an amendment exempting people who were trying to ride mules because he’d seen mules “about as cantankerous—almost, not quite—as a back row legislator (Republican) with a resolution in his hand.”

He went on to quote Shakespeare and the Bible, pointed out (factually) that there are no real cuss words in the Cherokee language, and stood up for Swain County, the place of his birth. He noted that the law was unconstitutional and likely unnecessary, because most of the folks he knew from there didn’t swear anyway.

But! People slip up, he noted, and they shouldn’t be punished for what they say when they do. “That’s all I want,” Hyde said, “a place of refuge, a sanctuary where a man can go and cuss with impunity.”

The speech was punctuated by loud laughter, and ended with a thunderous round of applause. And it worked. The News & Observer said the bill was “laughed to death,” and was killed with a lot of loud nos. Democrats in Swain County were relieved. “They elected a Republican senator and Nixon president and Holshouser governor,” one lawmaker said, “and now they’re trying to pass a law saying we can’t cuss about it.”

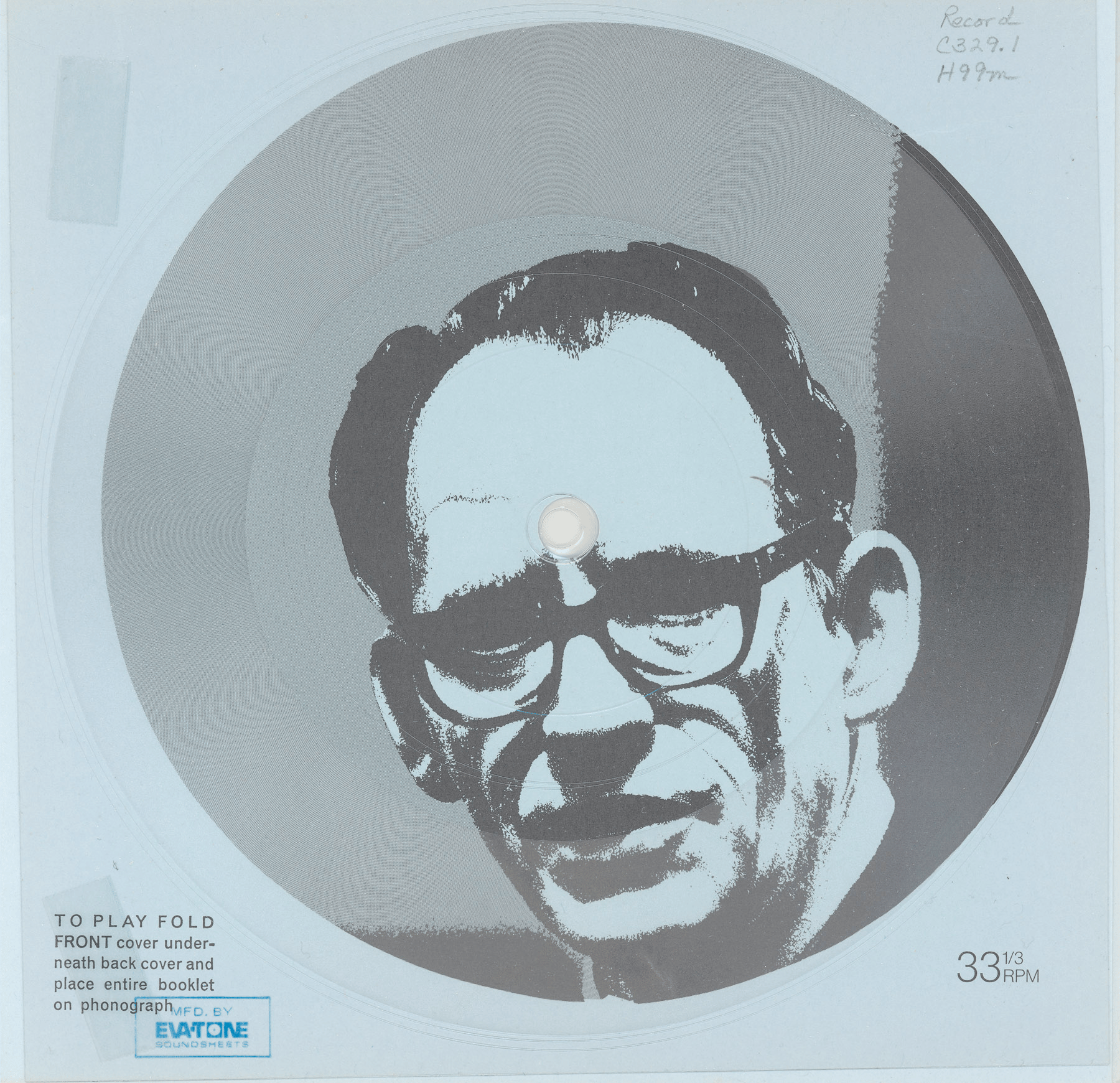

The speech was so popular that it was printed, in its entirety, in newspapers across the state. The audio, recorded from the house floor, was taken, pressed into records, and distributed across North Carolina. Hyde used the sales of it to help raise money for his unsuccessful campaign for Lt. Governor in 1976.

Herbert Hyde, sadly, was not nominated for a Grammy.

Swain County (along with Pitt County, where you might swear after watching a particularly frustrating East Carolina football game) was forevermore exempted from the profanity law.

This all might seem like small potatoes, really, at least in the face of the bigger First Amendment issues that folks are facing at this moment. Last week, the Daily Tar Heel devoted its entire 24-page issue to threats to free speech. Profanity wasn’t mentioned once. And decorum, while different, is not dead. After all, you’re still going to get looked at sideways if you scream “son of a bitch!” after stubbing your toe in a room full of preschoolers.

But small things add up, and have a way of influencing society. Allowing people a place to express themselves, even through swearing? “That’s not too much to ask, I shouldn’t think,” Herbert Hyde said in 1973. Or, as Bachman wrote decades later, “the

freedom to say fuck is protected under the First Amendment.” Times change. Rules don’t last. But people have always wanted the freedom to be themselves. Being able to talk about it freely? That’s some good shit.