Want to read stories like this sooner? Subscribe to the North Carolina Rabbit Hole for free.

In 1865, during the waning days of the Civil War, outsiders broke into North Carolina’s capitol building. They didn’t have any resistance. Governor Zebulon Vance knew that General William Sherman was heading his way, and he didn’t want Raleigh to have the same smoldering fate as Atlanta. So, he sent an envoy down to Sherman’s encampment near Clayton with a letter. Come on in, it said. The capitol building will be unlocked. Please don’t burn it down. He left the keys with an enslaved person, then fled.

When Union troops arrived, the signal corps went up to the roof and raised a flag to let other soldiers know it was safe to come into the city. Then they just started rooting around inside. They left graffiti on the walls, some of which is still visible up in the attic of the building. They looked for loot and important documents. Most of it had been sent off to Burlington for safekeeping (with one important exception). Sherman and his men were on the grounds for about two weeks before moving on to Durham. Then, the war ended.

I was thinking of that episode in history yesterday when I saw this:

Up until the afternoon, I was having a fairly peaceful day. In the morning, I got in my car and drove out to Hillsborough for my first official reporting trip since last February. I’m writing a story about the old Occoneechee Speedway for an upcoming issue of Our State, so I drove out there to check it out. It’s an original NASCAR dirt track that’s been completely swallowed up by forest and converted into walking trails. After a few laps there, I walked out along the Eno River to another park, called my wife and a friend, and then met up with a buddy of mine from Chapel Hill, where we masked up and talked in a parking lot. Then I got back to my car, saw a New York Times alert, and proceeded to doomscroll until midnight.

Whenever a big national story breaks, one of the first questions that someone in a local newsroom asks is: Could it happen here? It’s usually a cheap way to add context to a big important story. A lot of times, local TV folks will grab people walking in, say, a mall parking lot and ask them that exact question. Usually, the answers are underwhelming. Could the Olympics happen here in North Carolina? Probably not. Could Hugo Chávez happen here? He, um, sorta already did.

So, could North Carolina’s capitol building be occupied by an invading force? Yes. It already was. I know this isn’t a great apples-to-apples comparison to yesterday’s events, but it’s a reminder of how long it can take to unravel the damage done. In North Carolina’s case, one of the Union soldiers that was rooting around in the capitol found an old document in an upstairs cabinet, stuffed it in his bag, and took it home with him to Ohio. That document was North Carolina’s priceless copy of the Bill of Rights, which was finally returned to the state thanks to a sting operation set up by the FBI. In 2003.

Looking at it another way: The occupation only lasted two weeks. But it took 138 years to tie up one of the biggest loose ends from that occupation.

It’s unclear how the events of the last three days will play out over the next few years and decades. But if you’re wondering if they could happen here in North Carolina, the answer is: Some of them already did.

A Coup

The Atlantic’s David Graham, who calls Durham home, put the events of Wednesday this way:

Insurrectionists are attacking the seat of American government in an attempted coup, urged on by the president of the United States. Saying that feels melodramatic, ridiculous, and overwrought, but there’s no plainer way to describe what is currently unfolding.

He’s not wrong. The president urged an armed band of mostly men, a small militia if you will, to force their way into the U.S. Capitol building. Then, later, he gave them his support while gently asking them to leave. The president wanted to overturn the results of an election that he lost. He had no legitimate way to do it, so he riled up his conspiracy theory-addled base to intervene instead. Those are the people who stormed the capitol. They’re terrorists. This was a coup. Mild, as coups go. But still, a coup.

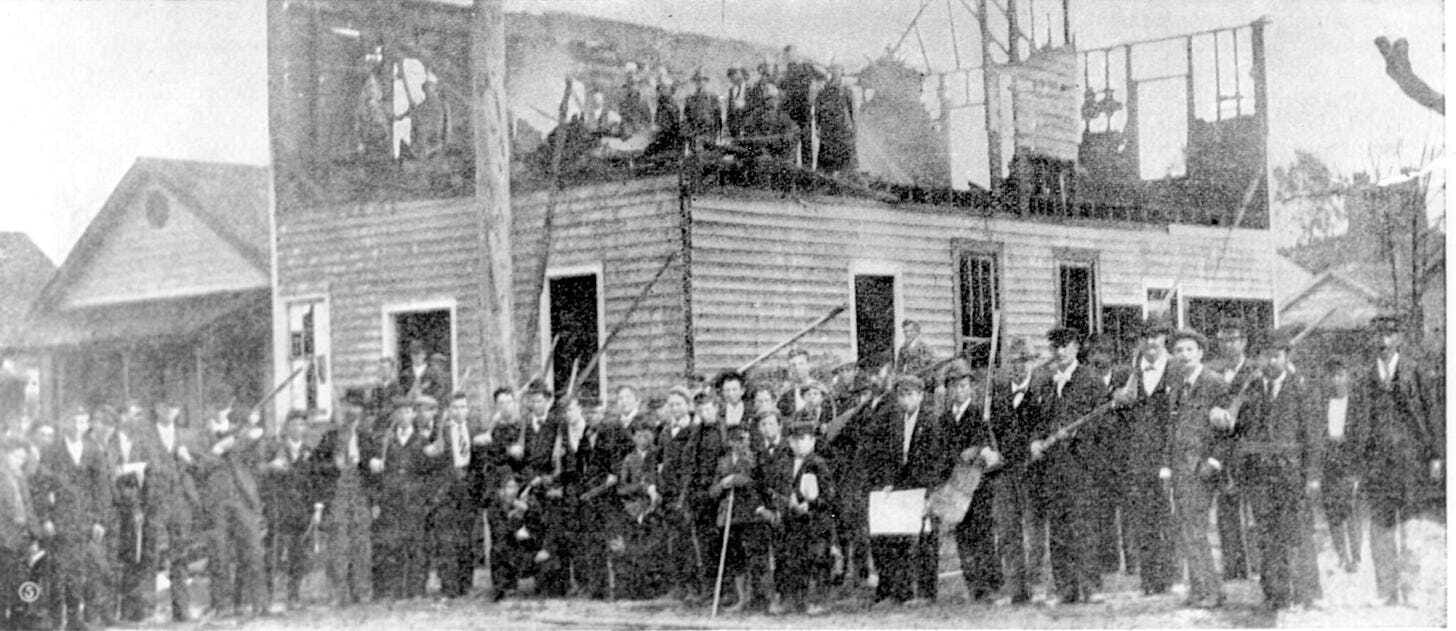

There has only been one successful coup on American soil. It happened in Wilmington. In 1898. Back then, the city was the largest in North Carolina. It was also majority Black, and progressive: The local government was biracial.

In November 1898, a group of white men, angry over the results of an election that reaffirmed that biracial government, formed a mob. They burned down the city’s Black newspaper, and killed between 60 and 300 Black citizens. The local government was replaced by white supremacists. Black businesses closed, and Black families left town. Wilmington became a white-majority city. Many of the organizers became politicians and governors. Nobody was ever prosecuted, and no Black person held office in Wilmington for the next three-quarters of a century.

That summary of this story is woefully short. There are a lot of more worthy books about the coup and its legacy, including “Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy,” and “Cape Fear Rising.” This Atlantic piece explains the political fallout from the coup that transpired more than a century later. But I’m always struck by two things about this episode. The first: So many people have no idea that this happened. That’s partly because, for decades afterward, the coup was wrongfully portrayed as a white effort to restore stability after a Black “race riot.” The other is just how hard it is to erase that hero’s narrative that surrounded the men who led the coup.

Hugh MacRae was one of them. In 1925, decades after the insurrection, he donated land in Wilmington for a park, with the stipulation that it was for whites only. The rule was broken by Black folks starting in the 1960s, although it wasn’t fully repealed until Christmas Eve 1980.

But long after that, the name remained. Finally, the New Hanover County commission came to a reckoning, and voted to change the name of Hugh MacRae Park to Long Leaf Park.

David Perdue and Pillowtex

Yesterday, the Associated Press called the second of two runoff elections in Georgia for Jon Ossoff, therby giving Democrats control of the U.S. Senate. It’s a truly historic moment in many ways, but during the campaign, I discovered something I hadn’t known before. Ossoff’s opponent, Sen. David Perdue, was the CEO of Pillowtex for nine months.

If you’re new to North Carolina over the last decade, this is another one of those stories that you may never have heard. A short recap: Pillowtex was the textile company that occupied the historic Cannon Mills complex in Kannapolis, but had fallen on hard times. It shut down for good in 2003, putting thousands of people out of work in the largest single layoff in state history. The factory and its historic smokestacks were imploded a few years later to make way for the North Carolina Research Campus.

Perdue was working at Reebok when Pillowtex hired him to be its CEO, but only spent a short time there. Those nine months ended up being quite consequential. From Politico:

Yet during a controversial chapter in his record — a nine-month stint in 2002-03 as CEO of failed North Carolina textile manufacturer Pillowtex Corp. — Perdue said he was hired, at least in part, to cut costs by outsourcing manufacturing operations overseas. Perdue specialized throughout his career in finding low-cost manufacturing facilities and labor, usually in Asia.

During a July 2005 deposition, a transcript of which was provided to POLITICO, Perdue spoke at length about his role in Pillowtex’s collapse, which led to the loss of more than 7,600 jobs. Perdue was asked about his “experience with outsourcing,” and his response was blunt.

“Yeah, I spent most of my career doing that,” Perdue said, according to the 186-page transcript of his sworn testimony.

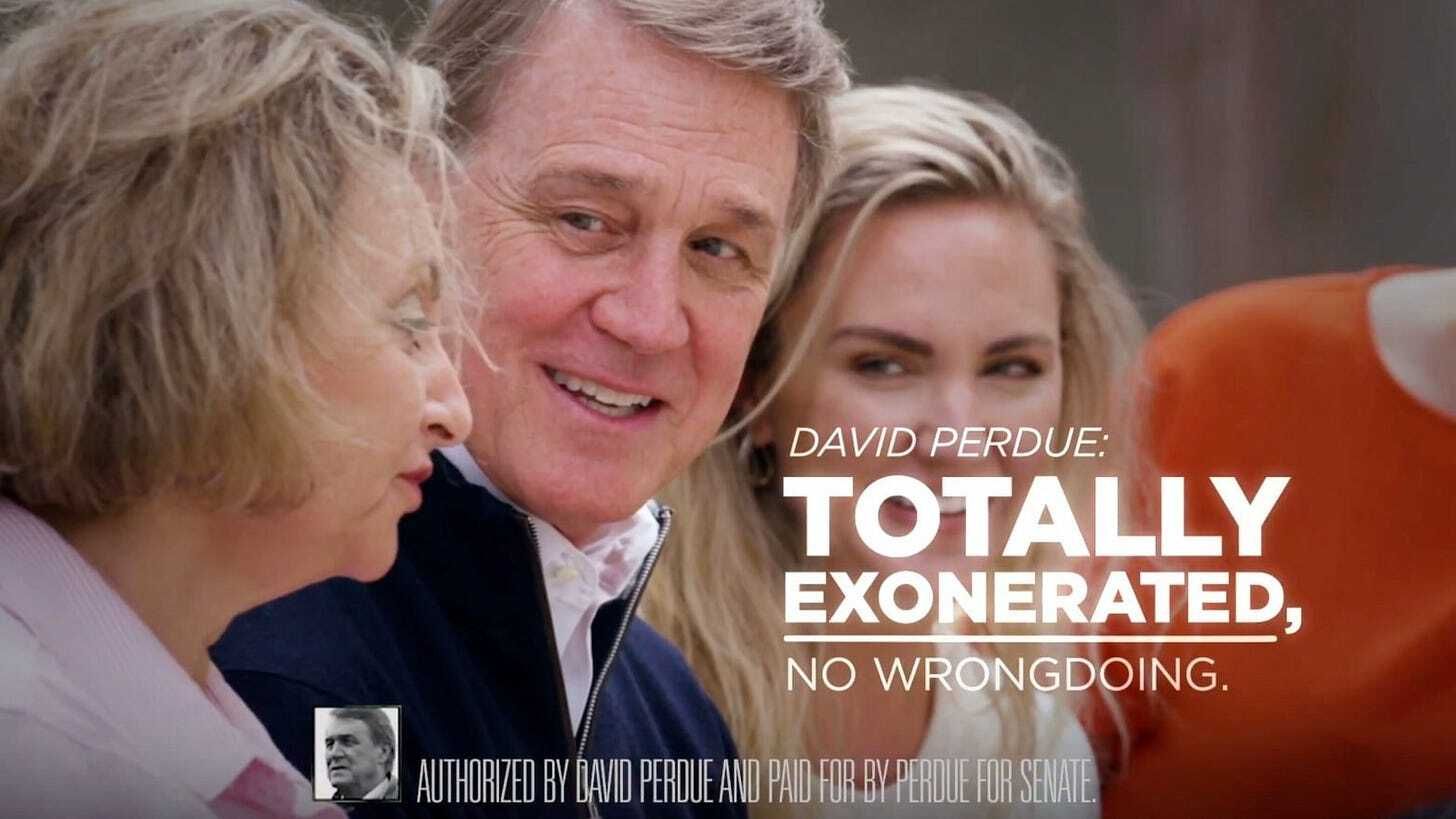

It wasn’t as if Pillowtex was doing well when he arrived. It was already in bankruptcy, and Perdue compared his tenure as CEO to “running into a burning building.” He was initially hired to run the company for four years, but left before the end of his first to run Dollar General. In 2014, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in Georgia on the basis of his business acumen, but the Pillowtex episode was made into a campaign issue by his opponent. It wasn’t a major factor in Perdue’s 2020 race. Insider trading was, however, leading to this remarkable screengrab from one of his campaign ads:

How To Win After Losing

Ossoff and fellow Democrat Raphael Warnock won Georgia in large part due to the work of Stacey Abrams, who also helped Joe Biden become the first Democratic presidential candidate to win in that state in 28 years. Her effort is a study in winning after losing: She came up short in her race to become Georgia’s governor in 2018, then kept working after that loss to organize and turn out the Democratic vote in her state. That work may have tipped the scales in the senate and the presidential race, and Democrats in other states are looking at her model to see if it might work for them.

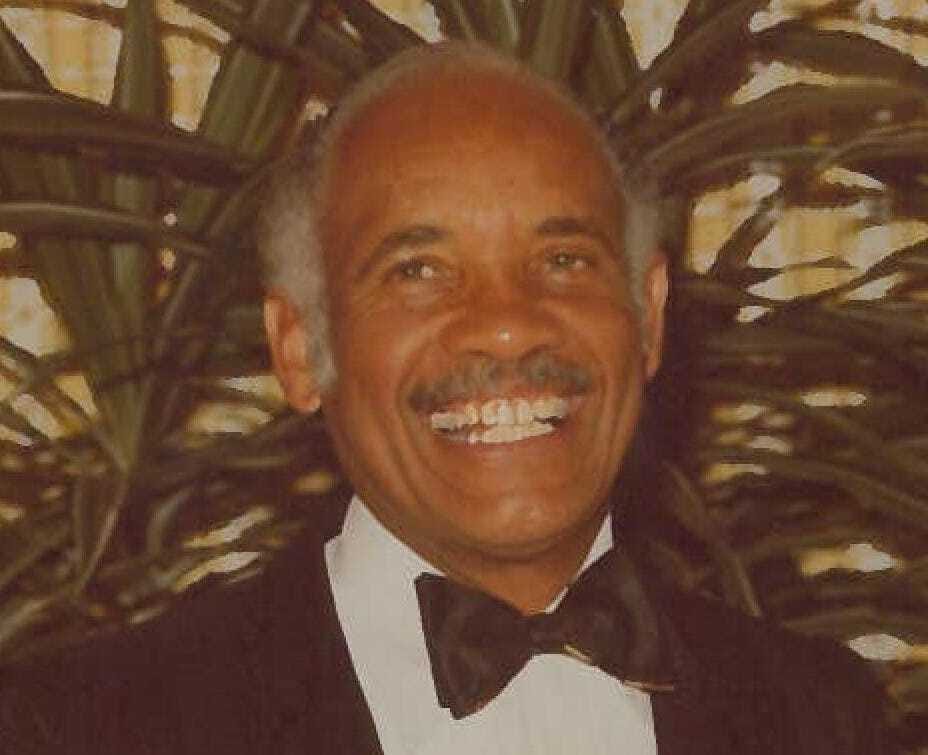

There’s some debate over whether North Carolina could be more like Georgia, or whether Georgia will end up, politically, more like us. Regardless, Abrams’s story of turning a big loss into an even bigger win reminds me of the story of the late George Simkins, a Black dentist in Greensboro who was arrested for playing golf on a white course in 1955. Simkins kept appealing his case all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which sided against him on a technicality. In the meantime, the city of Greensboro had closed all of its recreational facilities rather than integrate them. Simkins, realizing that the courts weren’t going to help him, decided to turn to the voters:

At the time, Greensboro only had about 5,500 registered black voters. So Simkins went to NC A&T, Bennett College, and Dudley High School, and registered teachers and students. Then he and others went house to house, registering black men and women, one at a time. Steadily, the number of registered black voters in the area more than doubled, to 12,000.

After that, Simkins started a letter-writing campaign, telling those newly registered voters to throw out the city councilmen who had voted to close parks, swimming pools, and tennis courts. It worked. In 1962, exactly seven years after his arrest for golfing while Black, Simkins was the first person to tee off at the newly reopened course.

Simkins went on to integrate Greensboro’s schools. He fought for better housing. He integrated the city’s hospitals through court action, and the ensuing legal case ensured that hospitals nationwide could not discriminate on race. He also changed the structure of Greensboro’s city council to a district system, ensuring Black neighborhoods had adequate representation. He turned his initial organizing into the influential Simkins Political Action Committee, which endorses and raises money for local candidates to this day. Simkins never ran for office himself, believing he could be more influential outside of the system. Still, he was tenacious, and anyone who played golf or tennis against him knew how competitive he could be. “Once he made up his mind, I don’t care what anybody else said, he was right,” friend and former state supreme court justice Henry Frye told me back in 2018. “George wasn’t one of these people who believed in waiting for things to change.”

—

h/t Andria Krewson

I, Jeremy Markovich, am a journalist, writer, and producer based outside of Greensboro, North Carolina. You can listen to episodes of Away Message to hear more about the theft and return of North Carolina’s Bill of Rights, as well as the remarkable life of George Simkins.

Author avatar by Rich Barrett.

If you enjoyed this edition of the North Carolina Rabbit Hole, share it with your friends and mash that subscribe button below.