I have a lot of questions right now. One of them is this: How could North Carolina select a slew of Democrats to fill some of its most important positions—Governor, Lt. Governor (eh, debatable), Attorney General, and Superintendent of Public Education—and also vote for Donald Trump? I don’t have an answer. I have theories. One is that statewide races feel concrete and important to peoples’ lives, while a vote for president is more abstract and vibes-based. But I don’t really know.

I do know that North Carolina has always been bipolar in its politics. Some of its most seemingly progressive policies were brought into being by white supremacists. Gov. Charles Aycock, who recently had his statue in the U.S. Capitol replaced by one of Billy Graham, was a champion of quality public education in North Carolina. But he also strongly believed that those schools should be segregated, wanted to take the vote away from Black men, and was involved in the 1898 Wilmington Coup. His name has been removed from all sorts of university buildings and city streets, but his birthplace is still an official state historic site. In 1894, Cameron Morrison “challenged over 200 negroes for illegal registration and prevented them from voting,” and remained dedicated to keeping Black people away from the polls throughout his career (He was against women’s suffrage because he didn’t want Black women to be able to vote). As governor, he was also a champion for the funding of public health and transportation and is still referenced as the “Good Roads Governor.” His name and legacy are still visible all around Charlotte.

There are many more examples of this. A few months back, I read “The Paradox of North Carolina Politics” by the now-retired chief political writer for the Raleigh News & Observer, Rob Christensen. The book came out in 2010, just before the election that gave Republicans control of the General Assembly (and also gave them the power to draw legislative maps that’ll keep them in power indefinitely). It’s required reading if you want to understand the historical forces that got us to the place we’re in today. Here’s part of his introduction:

National observers are often confounded by North Carolina’s puzzling politics. What kind of state is North Carolina? Was it the state that repeatedly sent Jesse Helms, Josiah Bailey, Sam Ervin, and a parade of other conservatives to Washington, or was it a state that elected a stream of center-left Democrats such as Jim Hunt, John Edwards, and Terry Sanford? North Carolina is, of course, both states, which is why it has been described as a political paradox. It is a state shaped by both fundamentalist churches and great universities, by poor yeomen farmers and industrialists, by an urge to move into the national mainstream and reverence for the traditions, both good and bad, of the Old South.

Or, more briefly: “What sets North Carolina apart is its progressive streak. The state’s voters are willing to elect liberals who they think will look after the average man—as long as he does not transgress southern racial customs.”

Which brings me to Frank Porter Graham.

If you’ve ever been to Chapel Hill, you know the name. There’s a child development institute, a student union, and an elementary school named for him. He had public power in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, but isn’t problematic enough to inspire a modern name-removal campaign.

Graham was born in 1886 in Fayetteville, graduated from the University of North Carolina, and returned there as a history professor and its first dean of students. He advocated for increased college funding, and saw education as a way to fight poverty. He fought for workers’ rights, and helped workers get legal representation during the Loray Cotton Mill strike in Gastonia in 1929. In 1930, he became UNC’s president. Two years later, he was named the head of the new consolidated UNC system, which included what today are NC State and UNC-Greensboro. He held that role for the next 17 years, was seen as friendly and well-connected, and pushed for free speech and racial equality.

By the standards of the day, he could also be controversial. People got upset at him when Bertrand Russell and Langston Hughes spoke in Chapel Hill. Graham got rid of Jewish quotas for applicants to the medical school. He offered to post bond for a socialist university graduate who was arrested during the 1934 General Textile Strike. He also tried to reform college sports by ending payments to athletes. (Graham’s brother, by the way, was Archibald “Moonlight” Graham of “Field of Dreams” fame.) Later in life, the United Nations appointed him to find a compromise between India and Pakistan in their fight over Kashmir. He died in 1972 at age 85.

But I’ve been thinking about Frank Porter Graham this week because of one specific thing: His race for U.S. Senate in 1950.

In 1949, North Carolina’s governor appointed Graham to replace J. Melville Broughton, who’d died in office. It was a surprise choice—Graham hadn’t ever sought out any elected position. The next year, Graham decided to run to serve out the rest of Broughton’s term.

By then, North Carolina was seen, nationally, as the Southern state that was the most progressive on race relations, albeit one that was still built on segregation. Black people were registering to vote in larger numbers in urban areas, but faced roadblocks in more rural parts of the state. Democrats had a lock on politics. Graham, although new to a political campaign, was a liberal Democrat who already had a lot of connections across North Carolina. Organized labor liked him. Newspapers supported him.

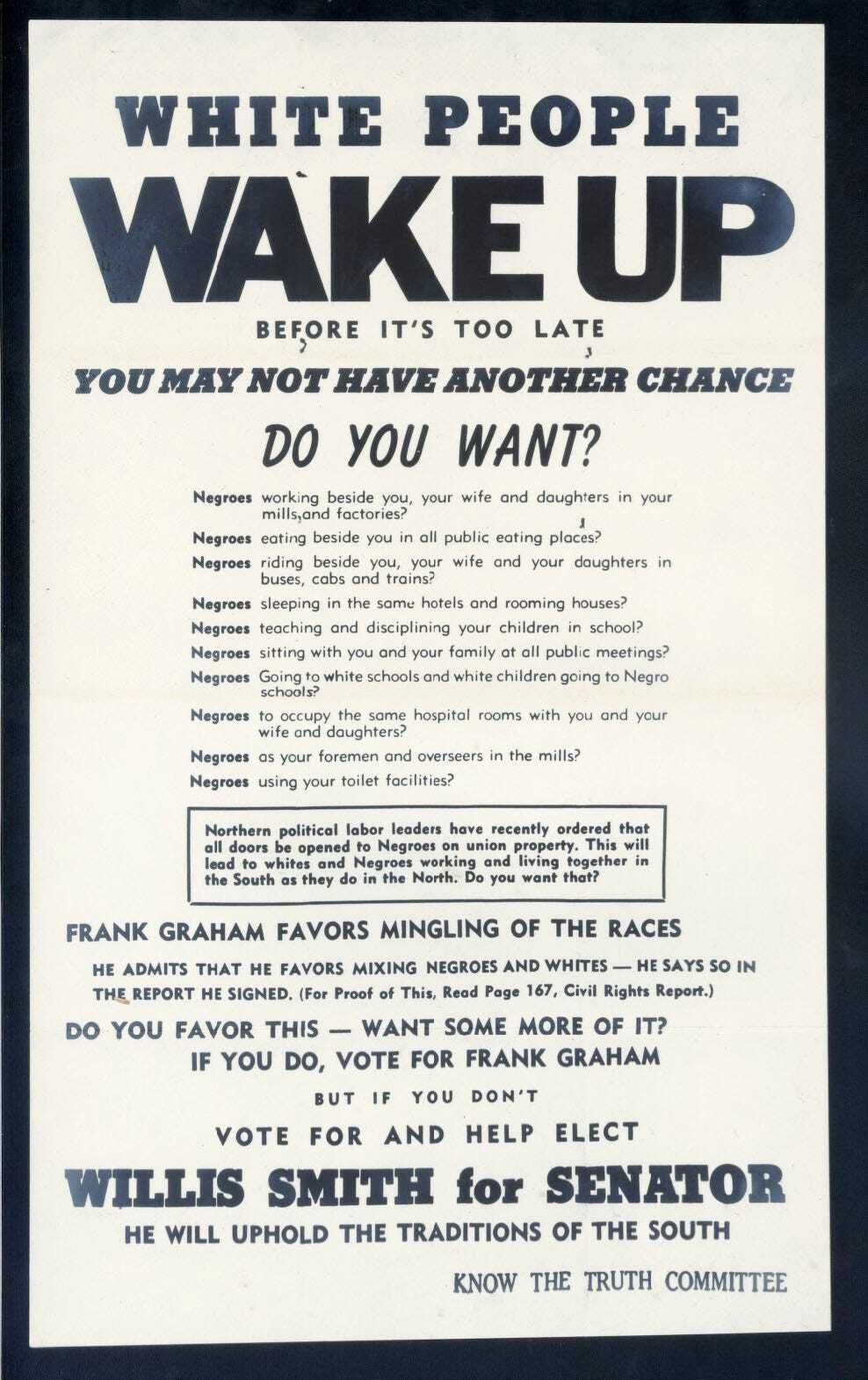

His opponent in the 1950 Democratic primary was Willis Smith, a conservative tax attorney from Raleigh who founded the Smith Anderson law firm. Initially, Smith’s campaign tried to paint Graham as a Communist sympathizer in the months after McCarthyism had begun. It wasn’t really working well, so they decided to add another theme to the mix: Race.

Soon, handbills started appearing across the state. One showed Black GIs dancing with white women abroad during World War II, and said that Graham wanted the same thing to happen in North Carolina. Another said Graham appointed a Black man to West Point. It wasn’t true. The ranking system was color-blind, the man was named a second alternate based on his exam scores, and never even got an appointment. Smith’s supporters said Smith himself didn’t have anything to do with the racial campaigns, but he also didn’t step in to denounce or stop them.

The race tightened, but in May 1950, Graham came out on top in an election that saw the biggest turnout ever for a Democratic primary in North Carolina. He had 49% of the vote, while Smith had 41% (former senator and Trump prototype “Buncombe Bob” Reynolds got a big chunk of the remaining vote). Under the rules, Smith could call for a runoff but decided not to, wrote a concession letter, and gave it to a press aide. That aide didn’t deliver it. Instead, he got people together to figure out how to get Smith to reconsider.

One of those people was Jesse Helms, who was the news director at WRAL radio. He started to run ads to encourage people to hold a rally in front of Smith’s house in Raleigh. They worked. Some 500 people showed up, chanted, and got Smith to call for a runoff the very next day.

After that, the racial tactics got nastier, culminating in this poster, which started to make its way around the state a week before the runoff. In bold font at the top, it read “WHITE PEOPLE WAKE UP”:

During the last week, Smith traveled across the state decrying Socialism. Everywhere he went, a band played his campaign song: “Dixie.” Graham started encountering more hostile crowds. A few times, people spit on him. A lot of Black North Carolinians supported Graham but weren’t able to vote for him. Many were registered Republicans.

In June, a record 550,000 people came out for the runoff election. That night, the results were in: Smith won by around 20,000 votes. He easily won in November.

During the runoff, Graham had his worst showing with white voters in Eastern North Carolina, where the Black population was the largest. “People became inflamed and aroused,” one clerk of court said back then. “It was impossible to head off the stampede … You could not reach them by appeals to reason, because there was no reason in them.”

But it wasn’t just the rural areas. As Christensen notes, the attacks also resonated with middle-class people in more upscale urban neighborhoods, some of whom worried aloud that Black students might go to white schools if Graham was elected. In Charlotte, he lost in the rich Myers Park neighborhood. In the end, Graham was undone by forces that played into voters’ fear of people who didn’t look like they did.

The immediate effect was chilling. “No politician could question segregation’s wisdom and expect to continue his political career,” writes Christensen. Indeed, the race was influential on people like Jesse Helms, who went to work for Smith and later became a U.S. Senator himself. But Graham also inspired more progressive future governors like Terry Sanford and Jim Hunt (whose daughter, Rachel Hunt, just won her race for lieutenant governor).

After the race, Graham moved to New York City. He gave speeches in support of Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that integrated schools and declared segregation to be “inherently unequal.” But he was done with North Carolina politics.

So what does this have to do with today? After all, Frank Porter Graham has been dead longer than most North Carolinians have been alive. Here’s one thought: After any election, people go searching for logic and reason. They look at demographics. Economics. Events. Ads. Actions. But I tend to think that in the end, these things win out: Insecurity. Emotion. Fear. They definitely did in 1950. And they definitely played a role in 2024. If you want people to do something, you get them riled up.

Anyhow, I’m still reading. Still thinking. Still processing. Sure, what I’m writing here is more of a brain dump than a sharpened argument, so bear with me. But I do know that there’s almost always a precedent for times that feel unprecedented. Or, to use a more famous and succinct quote: History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.