Bad Weather Isn't Enough To Make Power Companies Bury Their Lines. So What Is?

After storms and widespread outages, electrical companies and experts always say it's too expensive to put all overhead power lines underground. In the 1960s, they buried them for different reasons.

Whenever there’s a hurricane or an ice storm or nasty winds around here, I know what you’re gonna say. You say it every time!

No matter how many times you say it, though, the answer is always the same: It costs way too much to bury overhead power lines. After an ice storm in 2002, the State of North Carolina commissioned a study to look into it, and found that burying all lines would cause most people’s electric bills to go up by 125%, cost a total of $41 billion, and take 25 years to complete. (If they’d started with the project immediately after that 2002 storm, they’d still be working on it today!) It costs five to ten times more to put lines underground as opposed to overhead, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Underground lines don’t last as long, take longer to fix, are susceptible to floods, and you might have to cut down a lot of trees to put them in.

What is happening, however, is that most new developments across North Carolina (and elsewhere) are burying their lines, because it’s cheaper to do it when you’re already ripping up the ground during construction anyway. As of last year, Duke Energy said about a third of its power lines were underground, and that it uses data to figure out where it should bury outage-prone sections of its grid. Even so, places with underground lines can still lose power during storms, because those places are often still fed by above-ground lines, which continue to get pulled down by ice, knocked over by trees, run into by cars, or gnawed on by squirrels. In short, utility companies say you’d pay a lot of money to bury power lines, and the results wouldn’t be all that much better than they are now. “If we were to take all of the established overhead lines and try to place them underground, in many cases, we would not see measurable improvement in performance,” a Duke Energy spokesman told Axios Charlotte last year.

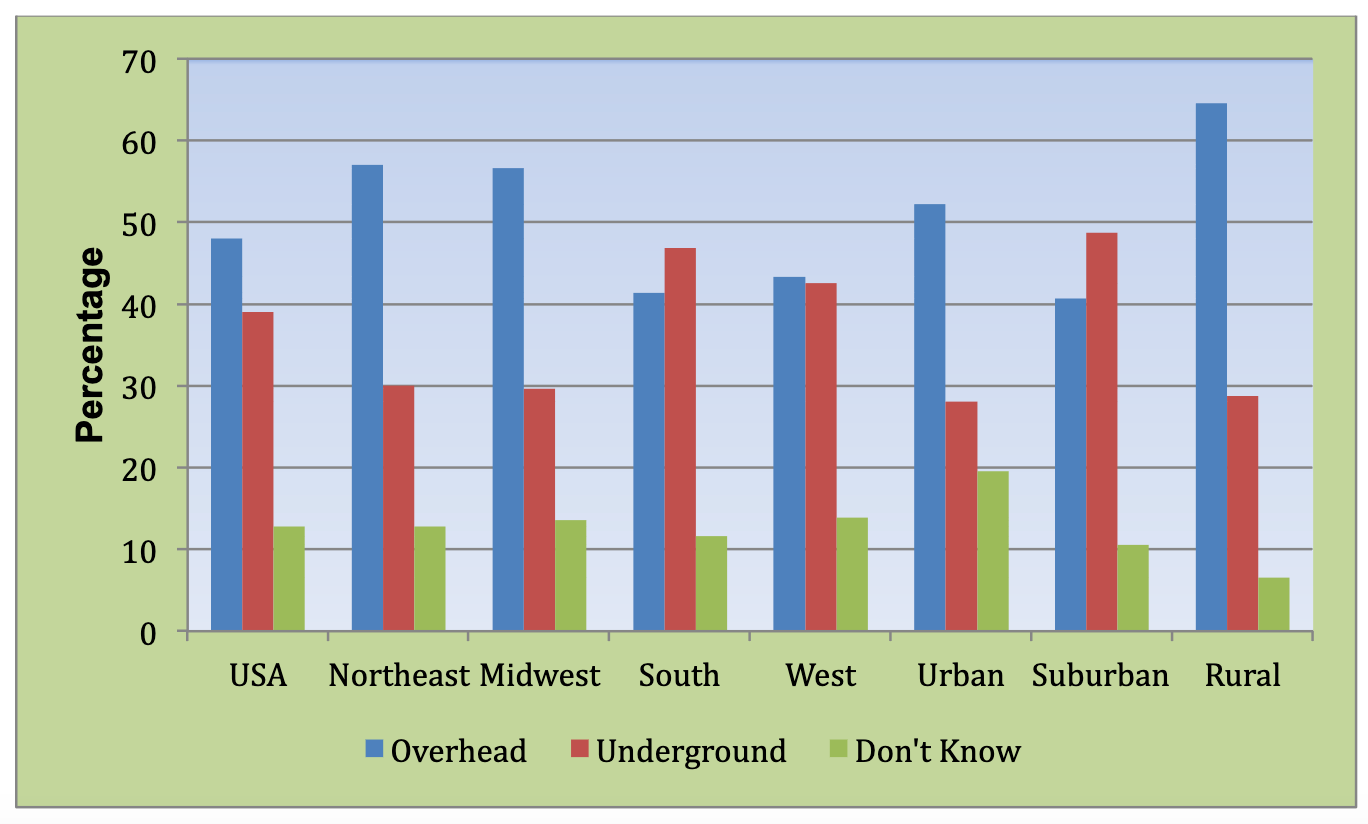

One side note: Power outages are another data point that feeds into the myth that northerners do winter better than southerners. “Northern transplants to the South claim that ice doesn’t knock out power up in cold country like it does down here,” stated a Greensboro News & Record story from 1996. But the issue is that the South, especially Greensboro, gets a lot more freezing rain and ice than the north does. “Snow doesn’t harm power lines,” the story states, “ice does a number on them.” Also, Southerners stated that they have a higher proportion of underground lines already, according to a 2012 survey by the Edison Electric Institute.

The EEI said other results from that survey illustrated the paradox presented by power lines: “customers want wires underground, but are unwilling to pay the cost of placing them there.”

However! There was a time when cities across North Carolina and elsewhere did decide to start moving overhead lines underground. It wasn’t because of the weather.

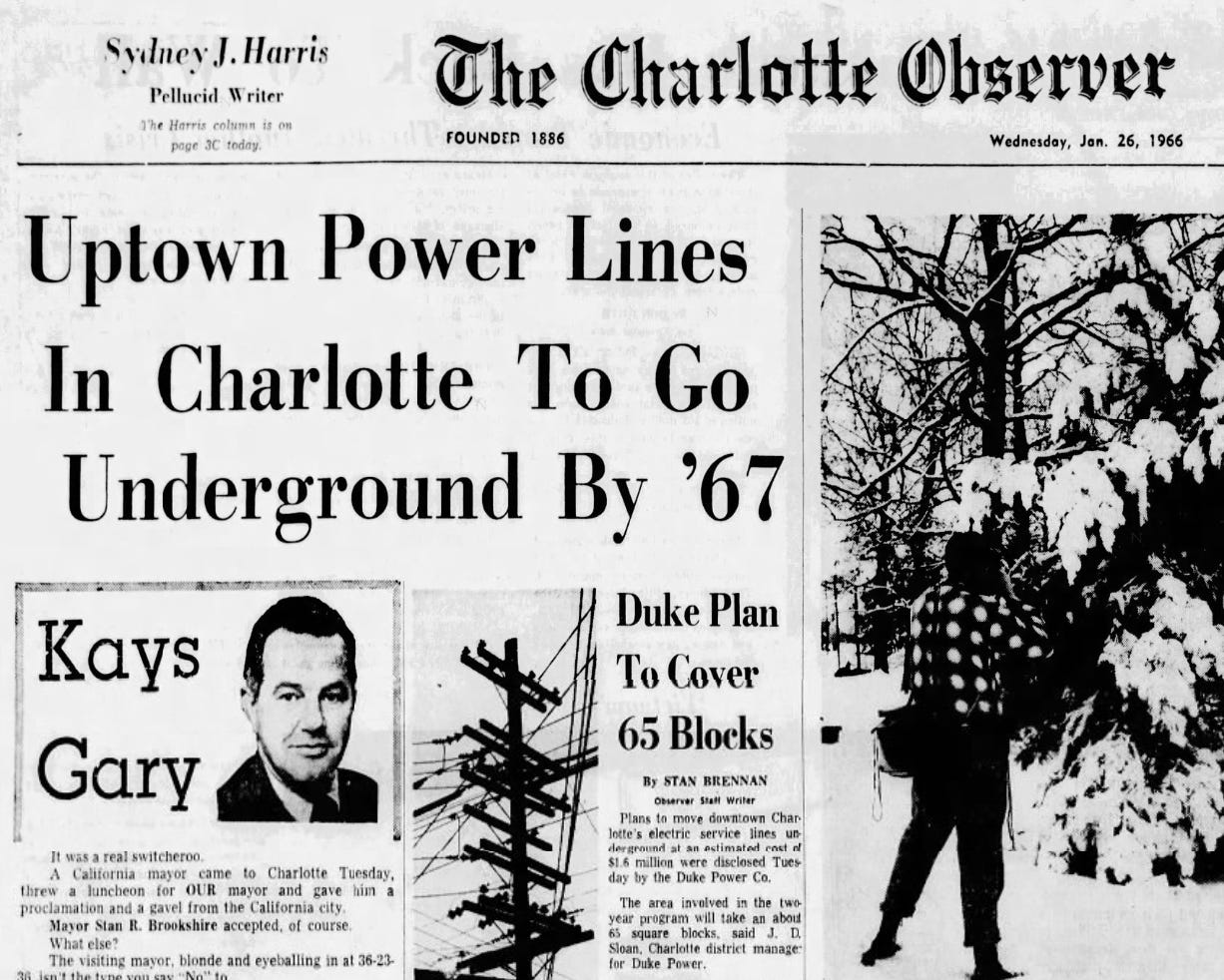

In 1966, a front page story in the Charlotte Observer noted an ambitious plan by Duke Power. Over the next two years, the utility company would take 65 square blocks worth of overhead lines and move them underground at a price of $1.6 million (that’s nearly $10 million in today’s dollars). Who would pay for it? Duke Power, that’s who.

So why did they agree to this expensive undertaking? For a couple of reasons. First: Uptown Charlotte was growing, and required more electricity than Duke could pipe in using overhead lines. The wires would have been too heavy for the poles. Second: There were fewer places to put those lines above ground, because new construction meant old alleys were going away. Those alleys were often the place where Duke put its lines, rather than right over the street were most people could see then. Lastly, people had stopped viewing power lines as a proud marker of progress. They started seeing them as ugly.

Eugene Levy, a history professor at Carnegie-Mellon University, took a deep look at the historic architecture of power grids in a 1997 paper entitled “The Aesthetics of Power: High-Voltage Transmission Systems and the American Landscape.” In it, he argued that cities had long wanted to get rid of overhead power lines, but utility companies were against it early on.

In effect, The American City argued in 1927, one could improve the urban landscape with ornamental streetlights, but all one could do with an electric distribution system that turned "Darkest Night into Brilliant Boulevard" was to place electric lines underground and out of sight.

City councils in Los Angeles and New York as early as the 1890s deplored the aesthetic effects of a jumble of overhead wires, but utility companies strongly opposed "undergrounding," to the point where they sometimes ignored ordinances requiring it.

In the early days, power was a largely local product, which came from nearby hydroelectric dams or uncomfortably close power plants. But over time, plants got bigger, demand went up, and big, high-tension transmission lines started to cut their way across the America landscape. At first, those lines were seen as majestic and modern. Then they ran headfirst into an environmental movement that started to gain traction in the 1960s. Here’s Levy again:

After World War II, Americans, who were being reminded that they were a "people of plenty," demanded ever-increasing amounts of electricity. Electric utilities eagerly encouraged the demand, and in meeting it constructed a vast, interconnected power system. Transmission structures, Young's "giant robots," were the most visible element of that system. But Americans also wanted to be able to "consume" the beauty of the natural landscape. To meet that demand, environmental groups in the 1960s, especially those identified with the natural beauty movement, sought to eliminate the last vestiges of aesthetic legitimacy from the structures by linking them to billboards and junkyards as "manmade objects d'horror."

Power companies realized they had a public relations problem on their hands. How to fix it? By creating something known as “beautility.” Here’s one summary of that movement written by Rebecca Wright in Environment, Space and Place in 2018:

In August 1965, Electrical World ran a special issue on “Operation Beautility”, a dynamic program dedicated to improving the appearance of electrical facilities across the nation. Following on from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s high profile White House Conference on Natural Beauty held in May that year, Electrical World outlined the problem facing utility companies across the country: “energy itself is invisible,” but “we cannot have it without power plants, switching stations, substations, transmission and distribution networks” cluttering the environment. The campaign for “beautification” led by LBJ’s wife “Lady Bird” Johnson swept the nation in 1965, focusing attention on the tangle of overhead lines, billboards, litter and junkyards cluttering the American landscape, and leading to the Highway Beautification Act in 1965. The “beautification” movement ushered in a new phase for utility companies, increasingly under pressure from environmentalists, regulatory bodies and the public, who protested against the continued expansion of energy facilities into increasingly urbanized districts.

Duke Power picked up on the beautility movement, using it as one of the reasons why it moved urban power lines underground in places like Hickory in the 1960s. “Duke Power is doing a substantial part in the improvement in making downtown Hickory beautiful,” a company manager told the Daily Record in 1965.

Putting urban lines underground was one thing. Doing the same thing with high-voltage electrical lines and giant towers was another. In 1967, people in North Carolina complained about new high tension lines going across the central part of the state. In response, Duke Power said it didn’t have the technological capability to put those lines underground. “We suspect in this case, beauty will be forced to give in to the utilitarian,” stated an editorial in the Hickory Daily Record.

Utility companies in the 1960s made an effort to design modernist-looking power poles to make them more palatable to the public, and tried to hide ugly power substations behind trees and other natural coverings whenever they could. Still, though, beautility didn’t last. “By the end of the 1970s, concern for the visual impact of power lines had been displaced by the controversy over possible health risks from their associated electromagnetic fields,” wrote Levy in 1997. “Rather than being defined as symbols of industrial progress or as monumental structures that are an integral part of the contemporary landscape, for most Americans transmission structures remain merely another example of the trashing of the environment.”

Even today, the ugliness of power poles is a big reason why people want to get rid of them. Well, that and the fact that we depend on electricity more than ever. “For customers, improved aesthetics and the hope that underground electrical facilities will provide greatly enhanced electric reliability will continue to be the driver for their desire for undergrounding of utility facilities,” read that 2012 report from the EEI. Cities like Anaheim, California have begun big projects to bury power lines, and California’s largest utility company is putting 10,000 miles worth of lines underground to help stop future wildfires from starting. Still, though, the EEI noted that “it is highly unlikely that any commission will ever mandate the complete undergrounding of any utility.” Meaning: Just go ahead and bookmark this story so you can come back to it after the next big storm.

This weather obviously hasn't met jon mfin sample

This doesn't have anything to do with power lines, but I have to ask: do you have the full clipping of that Charlotte Observer front page from Jan 26 1966? Because the article in the lower left of your screenshot appears to talk about a visiting mayor and before actually naming her it appears to give her measurements (i.e., bust, waist, hips) and that's... appalling? Maybe I shouldn't be surprised but for the opening description of a politician to be her hair color and body size has me gobsmacked. Is that just a thing that used to happen?