Longtime Rabbit Hole subscriber Lawton Ives emailed me to flag a fairly sublime state law that contains multitudes:

§ 20‑3.1. The Division of Motor Vehicles shall not purchase additional airplanes without the express authorization of the General Assembly.

“It might be worth looking into the origins of this provision,” Lawton told me. “Someone must have been having a little too much fun in the '60s or '70s.”

As in: Did someone from the DMV go out and buy an entire plane and forget to tell people? Did someone go on a jet bender? Did Orville Wright not go through the proper state procurement procedures?

At first blanche, this seems to be a strange vestigial organ that’s hidden in the North Carolina Code; an appendix that’s stuck on the large intestine of state traffic laws, some of which are no longer on the books. The first clue is in the notation: It was enacted in 1963 as an amendment on a bigger bill that was targeted specifically at the State Highway Patrol. Specifically: Troopers weren’t allowed to use planes to give you a speeding ticket. And not only that: It became much harder for them to buy any kind of planes at all!

It turns out that this isn’t just a law. It’s one of the few remaining legal remnants of an ancient beef between lawmakers and the head of the DMV.

Speeding Tickets Raining Down From Upon High

Allow me, briefly, to have an Andy Rooney moment. You ever notice how you’ve never seen a “speed monitored by aircraft” sign in North Carolina? Why is that? You’ve seen them in Virginia! That entire state is lousy with signs meant to scare you into slowing down. Radar detectors are illegal there. Police are notoriously strict about the speed limit. As of a few years ago, there were at least 425 signs in that state that threatened enforcement from the skies. Virginia wants you to know that doing 61 in a 55 is deep moral failing on your part. Thenceforth, your family should be shamed for generations.

Virginia wasn’t the one that started this, though. The idea of spotting speeders from an airplane began when the Iowa State Patrol started its Air Wing Unit in 1956 with two Piper Super Cubs. Many other states quickly followed. North Carolina didn’t get into the game until it bought two Cessna prop planes in January 1963 for $32,000. That spring, they took the planes around the state in a traveling speed trap carnival of sorts. They’d set up shop at airports across the state, tipping off local newspapers so reporters would show up and write up curious stories about it. Hence, in Albemarle, troopers made the front page after they caught a bunch of folks running stop signs and passing on double yellows.

The Stanly News & Press from April 12, 1963.

A lawmaker from Buncombe County was decidedly not a fan of this. Rep. I.C. Crawford felt, rather passionately, that the state highway patrol should do its patrolling on the actual highways and not in the air, saying the money for planes would be better spent on troopers and squad cars. “Next thing you know they’ll have space ships,” he told a reporter in 1963, not long after he introduced a bill to ground the Highway Patrol.

Crawford, a defense lawyer in his day job, was publicly suspicious that any airplane-assisted arrests wouldn't stick. “Every lawyer I’ve talked to said a man properly defended in court would never be convicted” on evidence gathered from the air, he told the News & Observer in April 1963 (Florida, which had also been using planes, had speeding cases thrown out on technicalities for a short time in the ‘60s). The Patrol said that wasn’t true: In a few short months, its planes had already led to 337 arrests, and 97 percent of those people were convicted. It noted that a single plane could do the work of 15 patrolmen on the ground.

Lawmakers didn’t care. The bill proved to be wildly popular, and passed the house easily. The senate was a little harder sell, though. So lawmakers added an amendment saying the planes could be used to help with traffic control at football games and the State Fair. It also allowed plane spotters to go after drunk drivers, street racers, or hit-and-run perpetrators.

A Beef With A Former FBI Guy

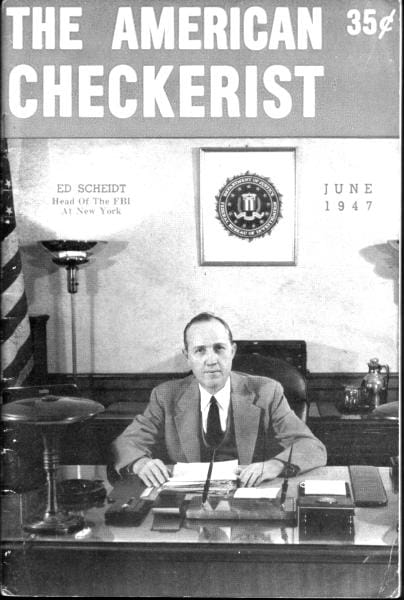

In this instance, Crawford may have hated the player and the game. He, and plenty of other lawmakers, were not happy with Ed Scheidt, the head of the Department of Motor Vehicles. Scheidt was a former FBI G-man who, among other things, was such a good checkers player that he made the cover of a national magazine dedicated to checkers.

Ed Scheidt: Tough on crime, tougher on a checkerboard.

It was a different time.

Scheidt became the head of the DMV in 1953, which also put him in charge of the Highway Patrol. He became the top law enforcement officer in the state. Scheidt quickly got the reputation as a hard-nosed guy who didn’t play favorites and didn’t give out favors, especially to friends of lawmakers who were trying to get the DMV to un-revoke their drivers licenses.

The man really hated speeders. In 1956, three years into the job, a magazine called Scheidt “The South’s Toughest Cop,” and said he would use “every trick in the book—plus some new ones—to crack down on speeders along North Carolina highways.” That led to complaints, and lawmakers were eager to find ways to cut down on his power. Right before Crawford introduced the plane bill, another one of his bills—which would have taken the Patrol out of Scheidt’s hands—was killed in committee. It wasn’t personal, Crawford said. How do we know this? “Nobody is trying to get Scheidt,” Crawford said. So there.

Crawford stated that his aim was to make roads safer by keeping the patrol out of the skies and on the ground. But he was also overt about the fact that his bill was a test on the power of Scheidt and the Patrol. “The SHP was created by the Legislature some 30 years ago and it’s still a creature of the General Assembly and should be,” he said during a hearing. In short: We’re your daddy.

Later, when Scheidt noted that a lot of other states used planes without many problems, Crawford said that wasn’t the point. “Mr. Scheidt, the public of North Carolina is against this,” Crawford said, noting that 999 out of 1,000 North Carolinians didn’t want traffic tickets from above. That’s a lot!

The anti-Scheidt sentiment ran so deep that the Senate also added a provision that would keep the DMV from buying any planes without the express permission of the General Assembly. Not just the Highway Patrol. The whole DMV! That amendment made it into the final law, which took effect on July 1, 1963. There you go, Lawton. Mystery solved.

Putting The Planes Back

So, how long did this aerial stranglehold on the State Highway Patrol last? Until Scheidt left, basically. Two years later, with Scheidt still at the DMV, some legislators tried and failed to allow the Patrol to enforce laws from above.

Then, in August 1965, Scheidt finally quit. “I ought to get out while I’m still young enough to do something else,” he wrote in his resignation letter (he was 62 at the time). Scheidt said he’d achieved everything he’d wanted in state government, even though he’d fought lawmakers every step of the way. He’d also, earlier that year, won his 13th (and final) North Carolina State Checker Tournament. He went out on top.

In 1967, with Scheidt finally out of the way, lawmakers decided to lighten up on the Patrol’s planes. Still, several lawmakers were worried that law enforcement from the air would be struck down by judges. So they created a bill that would allow pilots and observers to radio down to the ground to tell troopers if they spotted a speeder. But! The people in the plane wouldn’t be allowed to testify in court, and the law stated that it would be the “public policy of North Carolina that the aircraft should be used primarily for accident prevention and should also be used incident to the issuance of warning citations.” In short, unlike in other states, a Patrol plane could spot a speeder and give a trooper on the ground a heads up, but it was still incumbent upon that trooper to catch the speeder in the act. If, say, the driver slowed down before rolling past the trooper? Tough luck!

The General Assembly eventually lightened up. Pilots and observers were finally allowed to testify in court. In 1998. Three decades later.

So, can the North Carolina Highway Patrol catch speeders with planes or what?

Today, Highway Patrol policy now states that troopers can use aircraft (including helicopters and now drones) for “surveillance of motor vehicle violations.” So, technically, yes. The official policy, which was still law until last July, stated that the Patrol should use planes mainly for preventing accidents and issuing warnings. Catching speeders was legal, but officially frowned upon.

Compare that to Virginia. Hatin’ ass Virginia. Starting In 2000, that state decided to make up for lost time and allowed officers to track speeders from the air (they did it by seeing how long it took for a car or truck to make it between two painted marks on the road, and then using that time to calculate the speed). If someone was going too fast, the plane would radio down to a trooper on the ground, which would then pull the car over. That said, nobody has gotten a ticket that way since 2012. They’re not alone in giving up. New York State hasn’t actually used planes to catch speeders since the 1990s. Both states still have many of their warnings signs up, because they’re still allowed to enforce the speed limit that way. They just… don’t. It costs a lot of money, ties up a bunch of troopers, and is actually sort of inefficient. After all, you can watch all sorts of speeders from above, but you still need an officer on the ground to pull every single car over.

A “Speed Limit Enforced by Aircraft” sign on I-95 in Virginia, a few miles north of the

North Carolina state line (May 2025 photo via Google Street View)

There may be another reason why police in North Carolina aren’t eager to crack down on speeders from the air: They don’t get to keep the money. The state constitution says any cash collected from fines has to go back to the local county school district, so it’s not like you can rack up a bunch of revenue by nabbing speeders from the sky. This is also the reason why North Carolina, unlike Virginia or South Carolina, doesn’t have any small town speed traps. The economic incentives just aren’t there.

In any event, it’s still very possible to get a speeding ticket the old fashioned way in North Carolina, but except for a few holdouts (Florida! Ohio!), you’re much less likely to get busted by a plane in most places across the United States. Traffic laws have changed over the last six decades. But at least one remains to this day as a reminder that even back in 1963, people could do some extremely petty things with official legislation. Sorry, DMV. You want a new plane? Go ask your dad.